From Japan to Norway, by way of India and the United States

supersalone: the students have their say

Courtesy Pierre Murot

Sustainability, awareness, ethics, and innovation are the buzzwords for The Lost Graduation Show at supersalone: an exhibition that brings together 170 projects by students from 48 design schools and selected by Anniina Koivu. We asked 10 of them to tell us about their work

They are acutely aware of sustainability, first and foremost, of the opportunity to innovate products and processes thanks to the latest technologies. They are keen to reflect on the new issues such as the rights of those undergoing automatic facial recognition. They are bound up with their own identities and the areas they come from. More than anything, they are thrilled to be on an international stage and able to exchange ideas and visions after the lenthy period of isolation brought about by the pandemic. They are the young designers selected by Anniina Koivu for the Supersalone exhibition The Lost Graduation Show: 170 projects by students who graduated from 48 design schools in 22 countries in 2020-2021.

“It’s a broad snapshot of the global contemporary design scene. I can’t wait for the nationality or geographical origin of a project (or designer) to stop being important. With more interests and concerns in common, the old labels such as Italian, Scandinavian or Dutch have become more nuanced – design is becoming increasingly human (or environment) centric,” said the curator.

Koivu underscores the currency of the issues emerging from the students’ work: “The common theme to all the proposals was a collective awareness that materials need to be treated with care and respect, avoiding excesses.”

What can the industry learn from this? “The luxury of studying design means freedom. Boundaries are important for the work of designers, but schools offer the freedom of spaces for rethinking existing materials, playing with shapes and speculating on future production models. As with any new idea, experimenting with designs calls for time and space. In the end you have to face up to the real world, which is tightly regulated and sometimes limiting. Industry could help to smooth the path for unexpected ideas and provide a bit more time and space to allow designers to do what they do best: thinking outside the box and reimagining design for future purposes,” replied Koivu.

Meanwhile, we asked 10 students to tell us about their work.

Robin Bourgeois, 24

École des Arts Décoratifs, Paris

“À hauteur d’assise (“chair height”) is a project begun three years ago when I visited a Cistercian abbey near my parents’ house: it made a great impression on me, from the architecture to the furnishing to the daily lives of the monks. I then began to study the subject, went on retreats in a number of abbeys in various parts of France to experience the Cistercian way of life despite the fact that I’m not Christian. These unique experiences sparked six objects that transmit the heritage of these monks in our times: making do with little, building to last, living amongst nature, being attentive to our surroundings and contemplation.”

Daniel López Velasco and Ithzel Libertad Cerón López, both 24

Tecnológico de Monterrey, Mexico City

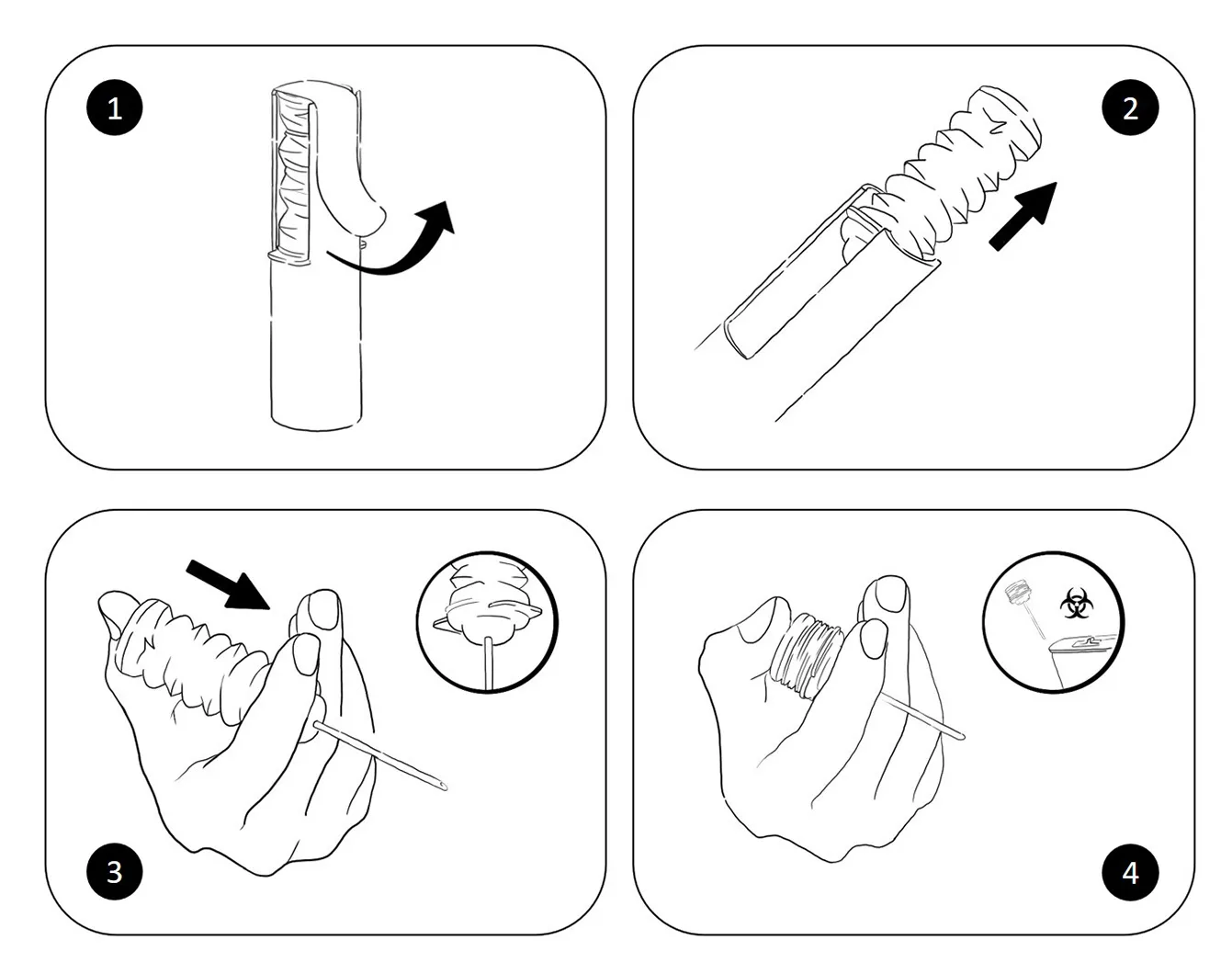

“Helix is a hypodermic syringe ready-filled with medicines or vaccines. We started designing it during lockdown after noticing that the health measures being taken all over the world were beginning to generate an alarming quantity of biological waste. If a vaccine or a treatment were developed, that would have led to the production of even more wrappers, cartons, syringes and needles. We were inspired by the morphine syringes used during World War II, with a folding section, and by the origami technique. For us, this project represents the importance of design in finding practical solutions of great social, financial and ecological impact.”

Rashi Sharma, 24

National Institute of Design (NID), Ahmedabad

“Embroidered Memories is a project that means a lot to me. It narrates the period of the Partition between Pakistan and India, when the State of Punjab was split in two. I was 11 years old when I started asking my family where we came from. As a Punjabi in Mumbai, I knew we weren’t from there. My parents told me that my paternal grandparents and my descendants were from Rawalpindi and Lahore, cities that are now in Pakistan. My grandfather had to escape from Rawalpindi as a teenager without his family. I lost my grandparents when I was 6, so I never had a chance to ask them about their history. During a Craft Documentation course in my third year at NID, I discovered the Khes weaving technique, which originated in the Punjab, and was influenced by Partition, like Phulkari embroidery. Researching my identity sowed the seed for this project. Phulkari shawls have become the medium for communicating migrants’ stories, along with Khes cloth.”

Courtesy Rashi Sharma

Amna Yandarbin, 26

VCUarts Qatar, Doha

“Yolkkh is a visual narration of the story of my grandmother, my mother and me during war, death and trauma, as well as hope, empowerment and growth. I wanted to use fabric for it, particularly the Noschi scarves worn by my people, named after the Chechen Russians. It’s a project designed to say a lot about me and my people, because it gives them a voice and introduces their identities to a world that largely knows nothing about them.”

Courtesy Amna Yandarbin

Matteo Brasili, 27

Naba, Milan

“My project is called Tre Miglia (Three Miles) and aims to combat water pollution with a new tool that can increase human abilities to collect the microplastics present in water, drawing on the habits of fishermen who go out to sea on a daily basis. It continues to evolve, thanks to the exchange of information with all the bodies and people who work at sea.”

Courtesy Matteo Brasili

Benjamin Bichsel, 28 anni

ECAL, Lausanne

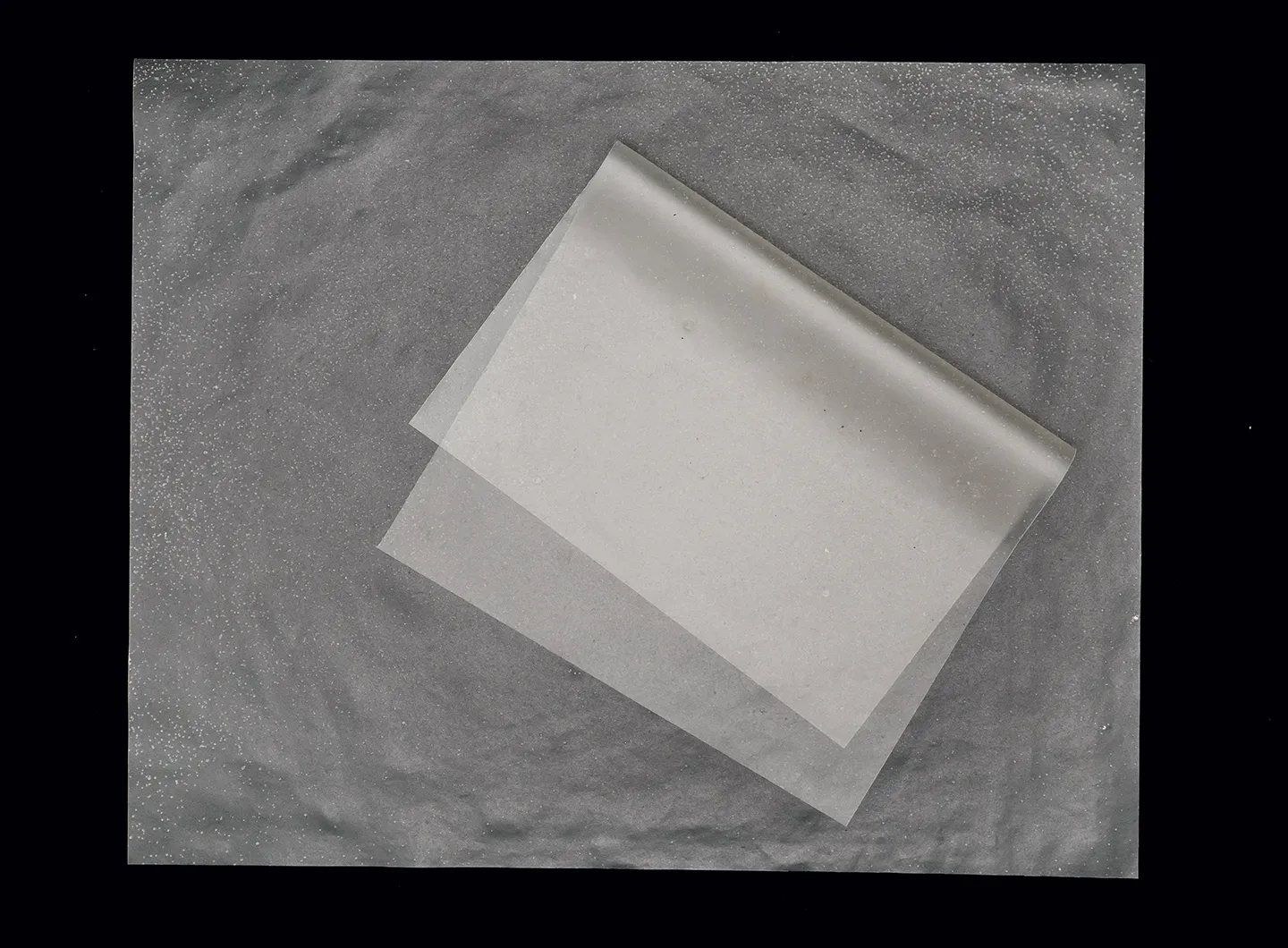

“I developed a biodegradable medical coat after realising just how much waste was produced in this field. I wanted to harness the latest innovations in the textile industry to come up with solutions for single-use clothing that was functional and agreeable to wear, while being eco-friendly. For me, the project was also an exciting opportunity to work on the entire life cycle of a product that was incredibly technically challenging yet extremely short-lasting.”