Functionality and beauty are ageless. Some objects remain current and iconic over time, even after many years. Anniversaries thus become confirmation of a value that continues to speak to the present

High Altitude Architecture (Part 1)

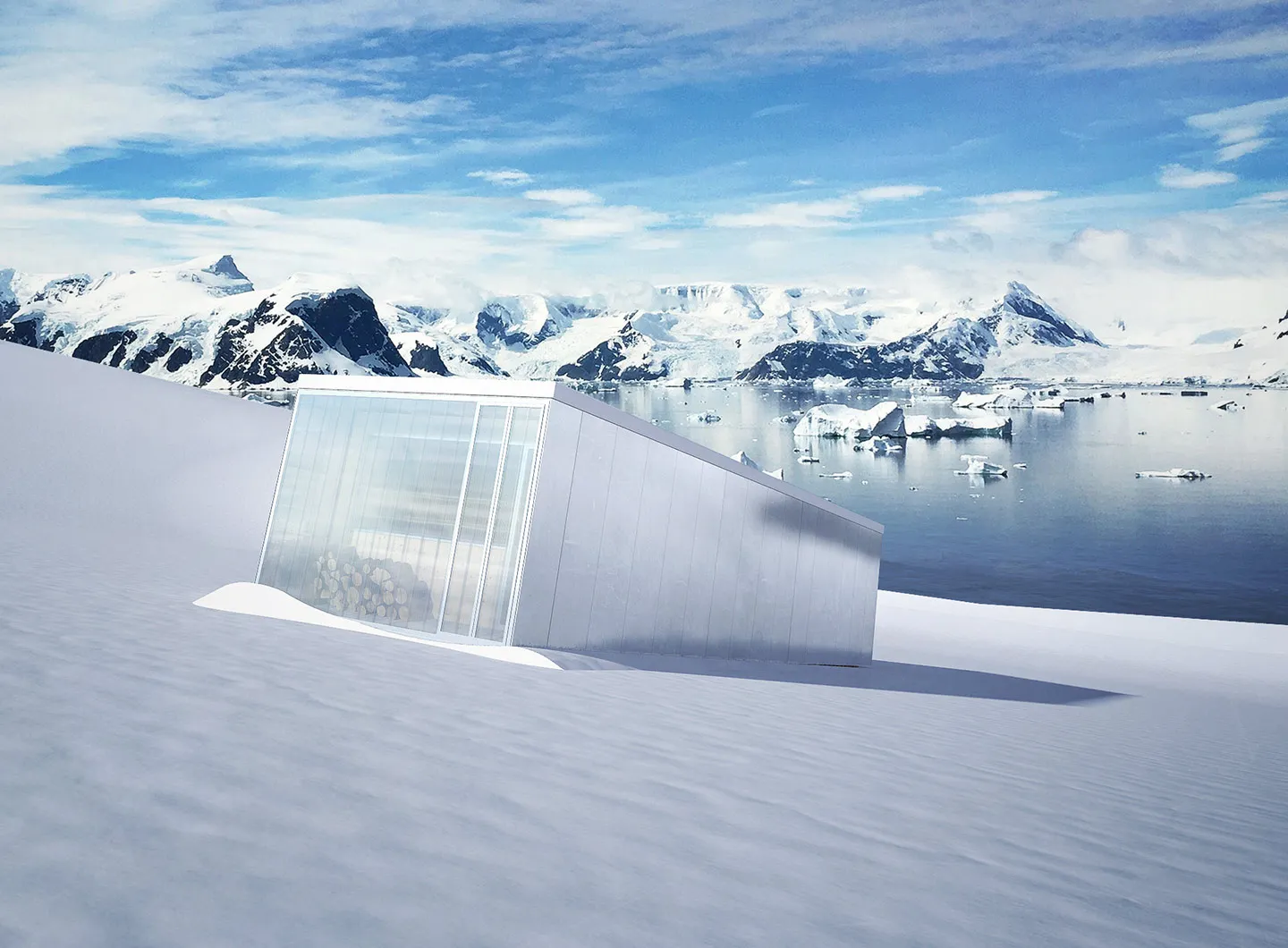

Our Glacial Perspectives, Olafur Eliasson - Photo Oskar Da Riz

Conquering dizzy heights with altitude-defying projects and their climatic and atmospheric challenges. Chosen above all for their emotional, cultural, engineering and historic value.

Over the last few decades, designing high altitude buildings has become the latest architectural challenge, as well as an obvious necessity, given the swift development of alpine tourism. Natural refuges had begun to prove inadequate for the needs of hikers, who started building resting places at strategic points along their ascents with materials found in situ or carried on their backs. The advent of the helicopter, in the Sixties, radically transformed the architecture of the refuges, their comfort and their supplies. The following is a “mixed bag” of projects, chosen simply for their emotional, cultural, engineering, tourist or historical value.

Our Glacial Perspectives, Olafur Eliasson

The high altitude artwork Our Glacial Perspectives by the Danish/Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson was unveiled in Val Senales last autumn. The work unfolds over a 400-metre “didactic” pathway broken up by 9 gates, along the crest of the Hochjorferner glacier, on Mount Grawand, culminating in a pavilion comprised of rings of glass and steel. A sculpture that channels “the power of art to create awareness through emotional, sensory, and physical experience” according to Ui Kerbi, one of the founders of TalkingWater, a platform for exchange and reflection on water, which commissioned the artwork. It is described by Eliasson as: “an optical device that invites us to engage, from our embodied position, with planetary and glacial perspectives.” The work marks the horizon, the cardinal points and the movement of the sun, directing one’s attention to a planetary perspective focused on the climate changes that also directly affect the glacier.

Ötzi Peak, noa* network of architecture © Alex Filz

Also on Mount Grawand but even higher up at 3,251 metres, is Ötzi Peak, another breath-taking construction, completed last summer by noa* network of architecture, which has more interesting alpine projects under its belt. Briefly, it is a panoramic platform that encompasses the summit cross, offering hikers and guests from the nearby hotel, the highest in Europe, a stunning alpine experience. Seemingly floating in the air, the platform is attached to the ground only where strictly necessary, its organic shape becoming a part of the landscape, echoing the surrounding topography. The platform’s “plateau grid” is supported by slender beams and surrounded by Corten steel slats, the original colour of which has changed as they have weathered, becoming at one with its surroundings. A funnel serves to guide viewers’ eyes towards the Austrian border, and the place where Ötzi, the Iceman, was discovered.

Messner Mountain Museum, Zaha Hadid Architects

From one peak to the next and to one of Zaha Hadid’s last designs, completed in 2015, the Messner Mountain Museum at Plan de Corones, in Trentino, 2,275 m. above sea level. With several high altitude architectural projects to its name, Zaha Hadid Architects came up with a truly cutting edge project. Ranged over a 1,000 m2 area, on three levels and largely underground, only a small part of the museum is built outside, making for minimal visual impact. This solution ensures that the temperature within the spaces remains constant all year round, also ensuring energy optimisation. Devoted to the history of mountaineering, the museum reproduces the look of the towering mountain, with its peaks and its stony massifs.

Luca Pasqualetti Bivouac, Roberto Dini and Stefano Girodo - Photo Grzegorz Grodzicki

We now move onto the Morion ridge in Valpelline, in Val d’Aosta, where the Luca Pasqualetti bivouac has stood since 2018, 3,290 metres above sea level. It was the idea of local guides, aimed at encouraging the use of the area’s important yet forgotten trails. The project immediately chimed with the Pasqualetti family’s desire to dedicate a bivouac to their son, a mountaineer who perished in the Alps. Designed by Roberto Dini and Stefano Girodo, in partnership with LEAPFactory, this minimalist wood and steel building with two pitches, based on the archetypal hut, is located in a remote and hard-to-access spot. Creating a structure isolated from any sort of network and able to withstand extreme weather conditions meant that the building had to be kept as simple and be as efficient as possible, as well as ultra-protected and resilient. Every single component was dry-mounted, recyclable and ecologically certified, and conceived with transportability and lightness in mind. The lighting relies on a battery-powered solar panel. The inside is a welcoming shell with a window affording a panoramic view of Monte Rosa and the Matterhorn.