A week of meetings, exhibitions and urban walks to explore how architecture can combat inequality in contemporary cities. From 27th October to 2nd November

In praise of light. The Tate's collections travel to Australia

The Passing Winter, 2005, Yayoi Kusama. Tate: Purchased with funds provided by the Asia-Pacific Acquisitions Committee 2008. © Yayoi Kusama. Tate.

An exhibition in Melbourne presents a selection of paintings, sculptures, drawings and installations on loan from the British institution. The lowest common denominator is light, understood both as a subject and means of expression

Extremely important in architecture, because it fills spaces and changes our perception of them, light plays an even more fundamental role in art. Over the centuries it has been, for example, a natural phenomenon difficult to represent, and for this very reason highly stimulating, a variable to be taken into account in painting en plein air, a tool by which to fix images on photographic paper or celluloid, or even the key element in the operation of installations that behave like stage machines. generating illusions of great emotional impact.

At the ACMI in Melbourne, a landmark in Australia for everything related to audiovisual languages and “screen culture” (a few months ago it also hosted the Milan Design Film Festival on transfer to the antipodes), one exhibition traces the last two centuries of art history using light as a thematic thread. Light: Works from Tate's Collection, running until 13 November, brings together over 70 masterpieces on loan from the noble British institution, which in addition to the two London exhibition spaces, Tate Britain and Tate Modern, also has regional outposts in Liverpool and Cornwall.

Light: Works from Tate’s Collection, exhibition view, photo Phoebe Powell

The exhibition curated by Kerryn Greenberg, former head of international exhibitions at the Tate and currently part of the curatorial team of the next Biennale of contemporary art in Gwangju, takes as its starting point the first half of the nineteenth century. This was a period when the work of artists was nurtured on the theoretical level by Newton and Goethe’s theories of color and vision.

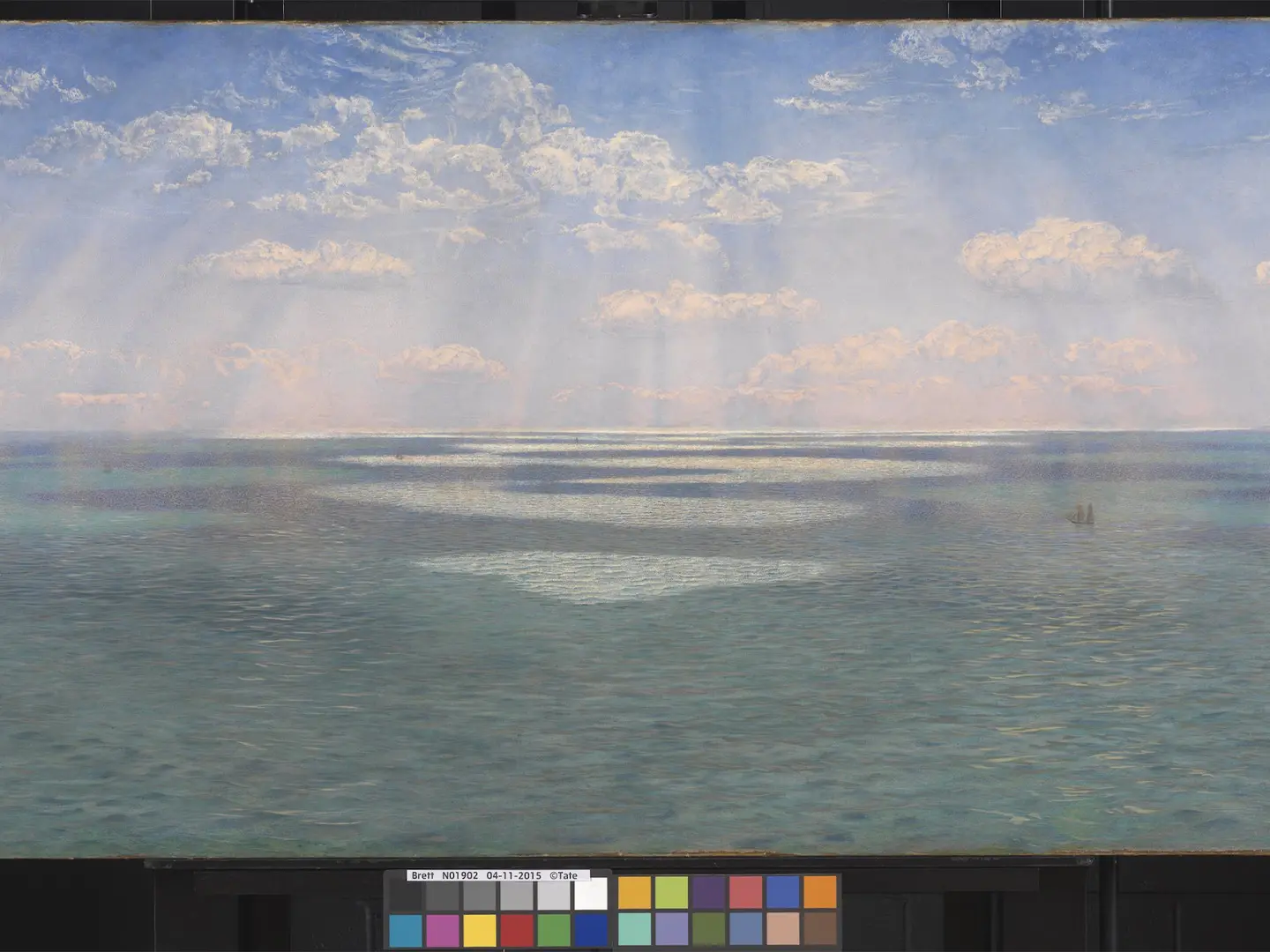

We find, for example, a series of oil paintings by William Turner and his "diagrams", the signs that the "painter of light" prepared to illustrate the reflective capacity of solids to students in the course he gave at the Royal Academy. Then there are works by John Constable and David Lucas. The variety and mutability of reflections in the water and the impact of atmospheric conditions on vision are also at the heart of Claude Monet's famous painting The Seine at Port-Villez (1884) and the works of Alfred Sisley and Camille Pissarro, which illustrate the Impressionists’ special relationship with light. A similar interest in the rendering of glimmering aquatic light is found in the view of the English Channel from the Dorset cliffs painted by the Pre-Raphaelite landscape painter John Brett (The British Channel Seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs, 1871).

The British Channel Seen from the Dorsetshire Cliffs, 1871, John Brett. Tate: presented by Mrs Brett 1902. Photo: Tate

A reinterpretation of art history through the prism of light cannot, of course, ignore the Bauhaus. In addition to giving the world iconic lamps such as the MT8 by Wilhelm Wagenfeld and Carl Jakob Jucker, the school founded by Walter Gropius in 1919 was the cradle of important studies of perception. The artists and designers involved in teaching in Weimar, first, and later Dessau would draw on this cultural achievement in their subsequent careers, spent in many cases in the United States.

László Moholy-Nagy, a mentor par excellence, played with the new languages of photography and cinema and set himself the challenge of incorporating a light source into an artistic artifact. His space-light modulator, featured in the film Lichtspiel Schwarz-Weiss-Grau (1933), is a "moving sculpture" that allows the light emitted by a series of light bulbs to dance through forms of different materials, from steel to plexiglass. Josef Albers worked for over a quarter of a century, from 1950 to 1976, on the interaction between color fields within a square, seeking, through repetition, infinite modulations of light and shades of color.

Starting in the sixties, artists such as James Turrell and Dan Flavin used neon bulbs and tubes as a means of expression, giving rise to works that transported the public into a dreamlike dimension. Turrell's Raemar, Blue (1969) deceives the viewer’s senses by creating the illusion of two-dimensionality in a three-dimensional space, while 'Monument' for V. Tatlin, part of a series of 39 sculptures made over three decades, pays homage to the project conceived by the Russian artist Vladimir Tatlin for the Third International, but left on paper, recreating it to scale with a series of fluorescent tubes.

Light: Works from Tate’s Collection, exhibition view, photo Phoebe Powell

Among the most spectacular works, in a selection that takes in kinetic art and film art, are the creations of two giants of contemporary art. The Passing Winter (2005) by Yayoi Kusama and Stardust Particle (2014) by Olafur Eliasson require the visitor’s collaboration to fully express their potential. The first is a sort of Wunderkammer, a cube of perforated mirrors that endlessly reflects the motif dear to Kusama of the dot, with shades of color influenced by the context; The second is a sculpture that stems from the artist's research into complex geometries, being formed by two irregular polyhedrons in suspension, one within the other. It creates different interplays of light and shade on the walls of the museum depending on the conditions of the setting and the viewer’s position.

Light: Works from Tate’s Collection / Melbourne, Australia

Until 13 November

ACMI, Fed Square Melbourne