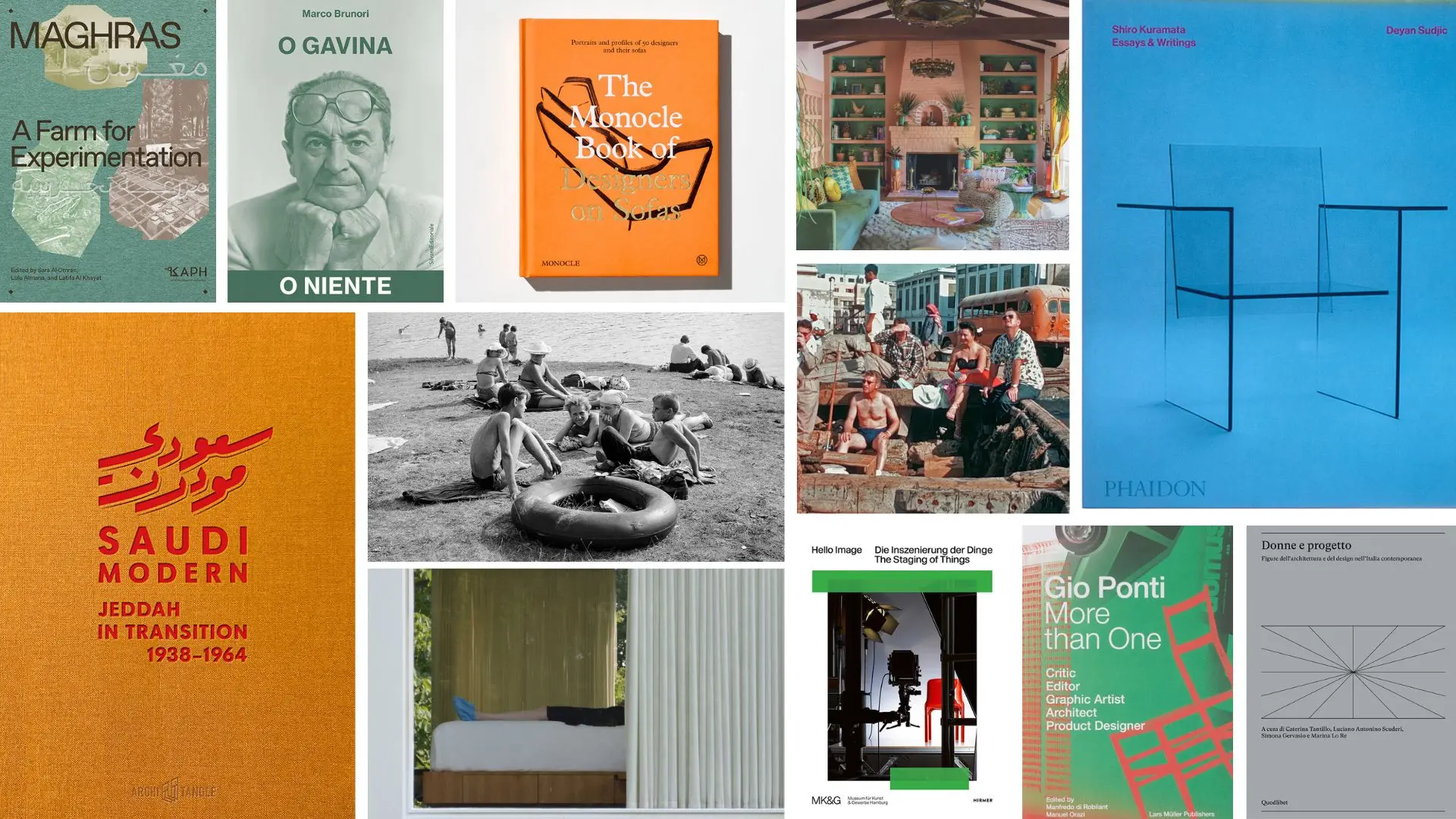

A journey through women’s interior design, three iconic monographs and the links between design, photography and marketing, up to the transformation of Jeddah, social innovation and a reportage by Branzi and... 50 designers on the sofa

Rosa Rogina: LFA, a festival to “act” on our city

It takes two, Ph Agnese Sanvito

An architect, researcher and curator, Rosa Rogina is the new Director of the London Festival of Architecture, the world’s largest event in the industry. Salone del Mobile.Milano met her in London to discuss plans and expectations of the festival’s upcoming edition.

With a legacy of 17 editions and the title of the world's largest annual architecture festival, the London Festival of Architecture (LFA) has become an institutional celebration for one of the most forward-thinking architecture hubs globally. Reflecting on the past two years of Covid-imposed restrictions, which provided the festival with a multimedia face and new, important themes to address, the LFA is taking on an innovative direction in June 2022 under the guidance of the recently appointed Director Rosa Rogina.

An architect, researcher and teacher, Rogina is the former LFA Programme Director since 2016 and has got curatorial experience at international design fairs under her belt, from the 2018 Venice Biennale to the Vienna Design Week in 2020. Gentle but passionate, Rogina is well-aware of the British capital’s most pressing challenges, from climate action to unequal provisions to women’s safety in the streets, and feels the call to arms for design to face them. Hence, the theme Act for the upcoming edition of the festival. “It’s really the moment to shift our awareness into action,” she said when she met us to talk about plans and expectations for the next LFA.

London Festival of Architecture (LFA) and Architecture LGBT+ Installation

A new goal of the LFA, and one which will be growing, is the festival as a vehicle to change the city. It will be less about displaying great architecture in a museum environment, and more about showing people the value of good design in the spaces and places that are relevant to them. And this is because Covid has shown has that changing our cities is possible. Think about Soho and other areas of the City, where councils were quickly able to close off the roads to traffic and allow alfresco dining and other pedestrian-friendly activities, within a few weeks. We are really keen to be at the forefront of that conversation so. And the festival has tried that approach before, much before my tenure at the LFA, in the 2008 edition we closed Exhibition Road in South Kensington for a long weekend, and that's when the Kensington and Chelsea councils realised it was quite nice to offer that space to pedestrians. That's why now it's shared surface, the design that we can see there now is the direct consequence of that initiative, and I think that's where the role and the focus of the festival should be, people are starting to see us as a series of interventions rather than just an event. Now we are in this climate conversation and we are looking at ways to green the roads with a set of installations looking related to biodiversity and ecology. We want to work to create an impact and make it last even after the festival days.

So, it's really interesting because pre-Covid, digital has always been a big nono for us. But now we are creating a whole new kind of engagement from everywhere in the world, without the need for people to fly to London to experience the festival, and this also creates awareness around the carbon footprint that events like these normally have. Also, the use of technology to host digital conferences allows us to disseminate the recording, or part of the recording, event post-event. I think that moving forward, our ambition will be, of course, to go back to pre-pandemic times, but we don't want to fully discard what we have learned and we will always keep part of it digital.

Windflower Ph Luke O'Donovan

The number one priority will be to democratise the debate. If you speak with people about design, film or fashion, they have opinions, but as soon as you mention architecture, it's almost as if we are talking about medicine or science. And then you think, well, all of us are using buildings, all of us populate domestic and public environments, so we should have opinions. But people don't feel empowered enough to have a say in those conversations. The second thing we are really passionate about is working with young emerging designers and architects who, unfortunately, in this city have quite a hard journey from finishing school to setting up their own business. So, what we started to do, and that’s becoming bigger and bigger, is running design competitions as a way to offer access. In 2017, we did our first significant one working with the Dulwich Picture Gallery in Southeast London which is a gallery of old masters’ paintings, quite a unique place, but with an extremely limited and predetermined audience. We ran a design competition for a temporary pavilion in their garden, as a vehicle for us to appoint young designers to get their first significant cultural commission, and to bring those new audiences to Dulwich Picture Gallery as well. The initiative became biannual and over the past few summers, the gallery’s audience has completely flipped, becoming much more diverse and young. The first commission was done by IF_DO Architects and the project was really kind of the launchpad for their career, and the second one was delivered by Yinka Ilori with Pricegore Architects and that was his first big piece of work.

I am a teacher at university myself as well, and I have to admit that the demographic of the students is getting more and more diverse and there has been a shift in the whole academic agenda. I think that there has always been a separation between academia and socially and politically aware practice, but we are witnessing a massive shift, and even the movements like the New London Fabolous are now celebrated within academics. There are some topics, such as diversity or carbon footprint, that used to be only a tick box exercise, while now they are at the forefront of the conversation.

Poliform, Ph Agnese Sanvito

Colour is clearly a great way to capture the public’s attention, and even us with the LFA end up commissioning quite a lot of pieces that are colourful by their nature and I think that is great if you do in the public realm because through colour you are guiding people’s awareness and kind of curating their experience. So inevitably, yes, it will be present at the LFA, especially because temporary installations allow us to use bold elements to kind of push boundaries which otherwise would not be possible to happen. Colour is certainly good but whoever uses colour has to be aware of the powers and possibilities within that particular tool. It’s about embracing and empowering different communities, so colour also needs to change to reflect that correctly. Another element I appreciate of the movement is that it pushes designers to find more positive ways of expressing themselves in public rounds. I think at the moment the challenge is, how do you continuously bring in new people and make sure it’s not always the same few names?

I wish that we can continue to see the empowerment of everyone, especially those that perhaps didn't feel included in the industry previously, infringing a much wider group of people and breaking bias that only experts can have a meaningful conversation about the built environment. And this hope comes from my personal background too. I often hear my colleagues back in Croatia saying “Oh, I wish I could do this”, I feel like everybody is dreaming big, but no one is really daring to try. If someone told me ten years ago that I will be directing the LFA, I would have never believed it, but here I am and I hope this can be a message of inclusion and empowerment.

Formafantasma on Salone Raritas

After the “Drafting Futures” Arena conference space, the Salone Library, and the Corraini Bookshop, the Formafantasma creative duo – Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin – has also designed the new “fair within a fair” setup dedicated to rare objects. Here’s their preview

Salone Selection

Salone Selection