From Japan to Norway, by way of India and the United States

Anniina Koivu: young design generation

200 students from 22 different countries, 48 design schools for a large exhibition, the only one of its kind. The Lost Graduation Show, the “supersalone” event devoted to the design schools, is on at the Rho Milan Fairgrounds from 5th to 10th September. Anniina Koivu, the curator of the exhibition project, talks about the urgencies, the new languages and the desires of the new generations of designers.

How did the idea for the exhibition arise?

When Stefano Boeri invited me to be part of the curatorial group for “supersalone” he asked me if I wanted to do something with students and the schools. So I suggested a large exhibition, which had never been done before and which represents a unique platform for young designers right in the heart of the design industry, in the fairground pavilions.

What was the concept?

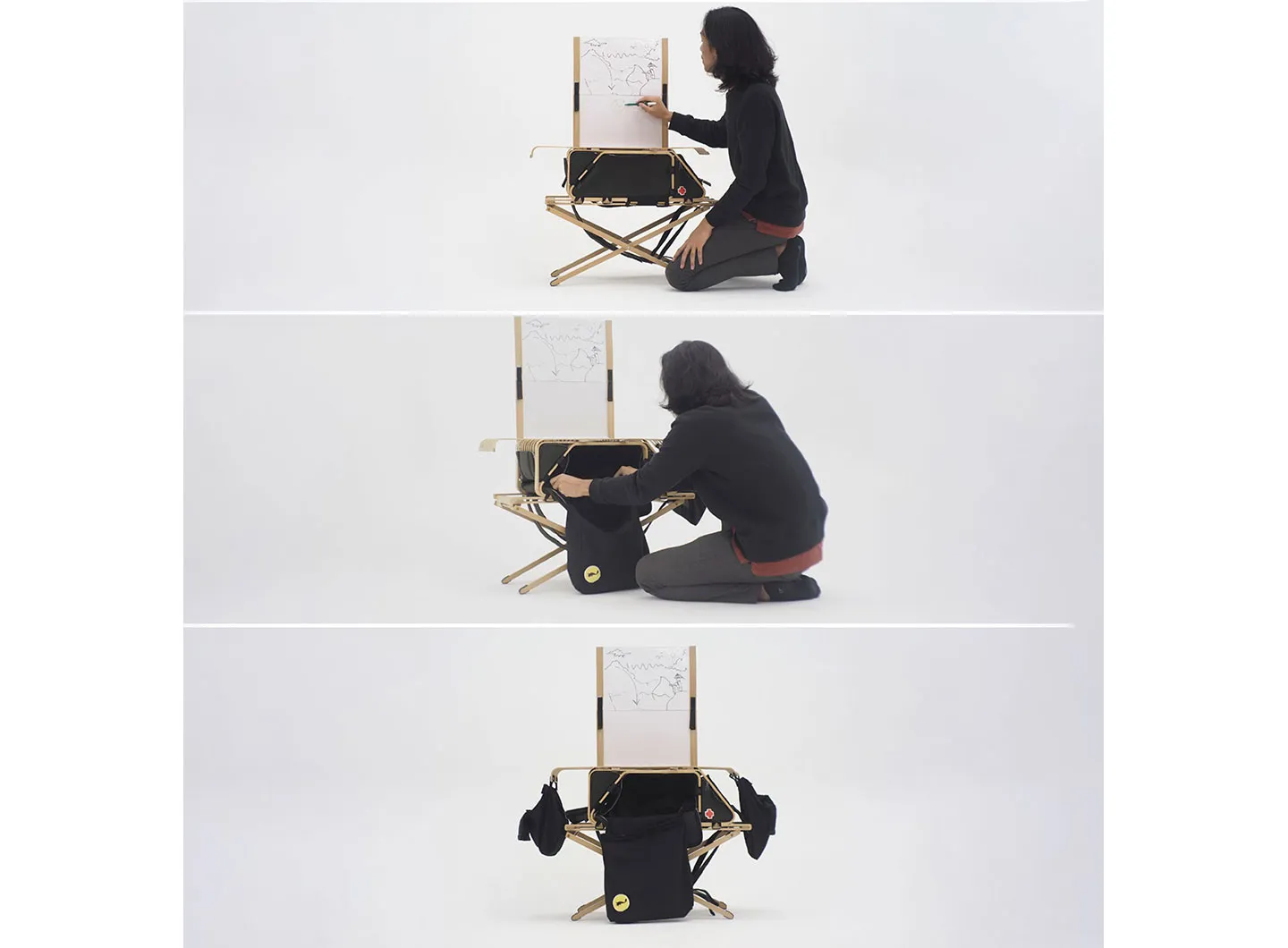

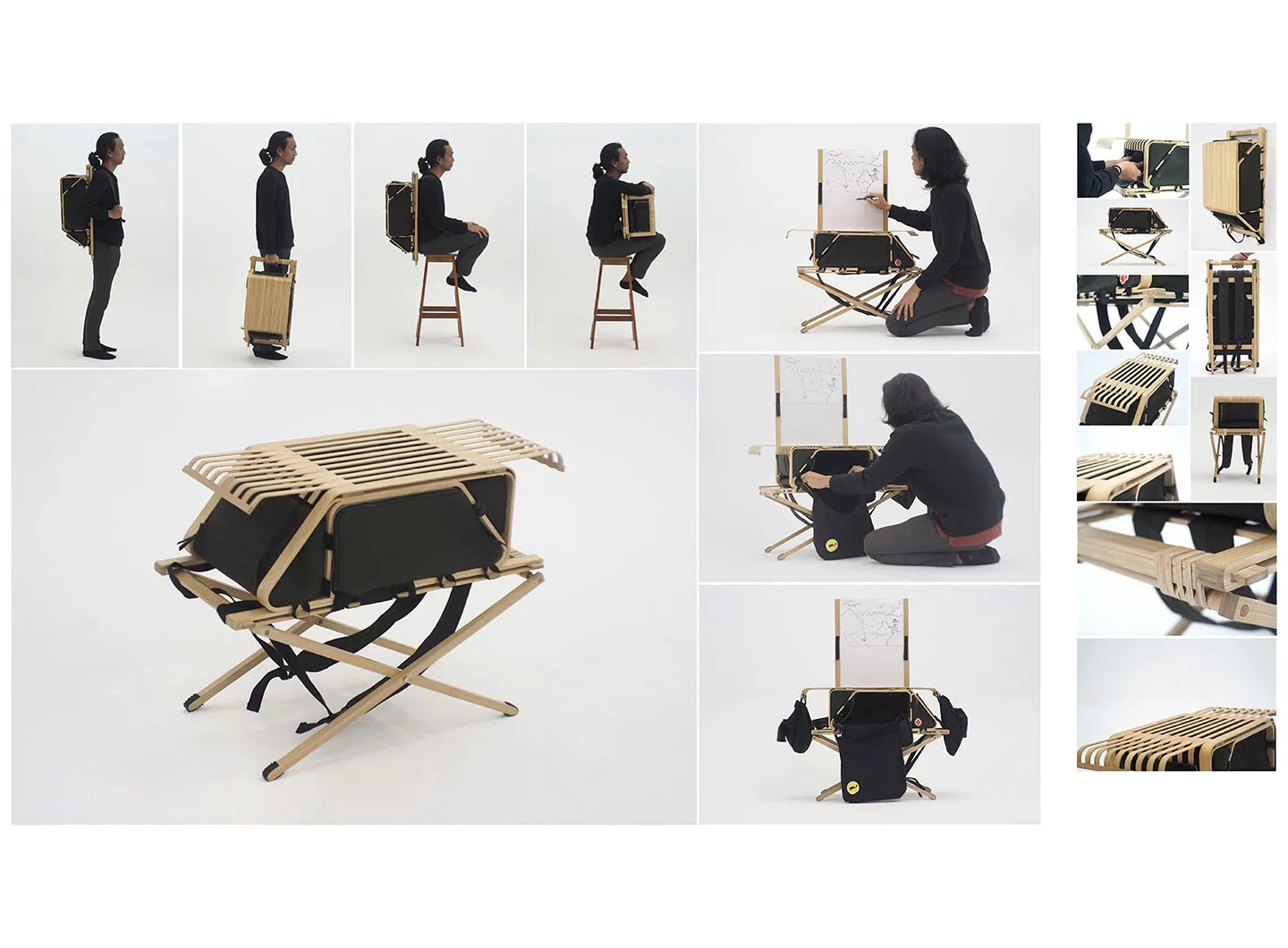

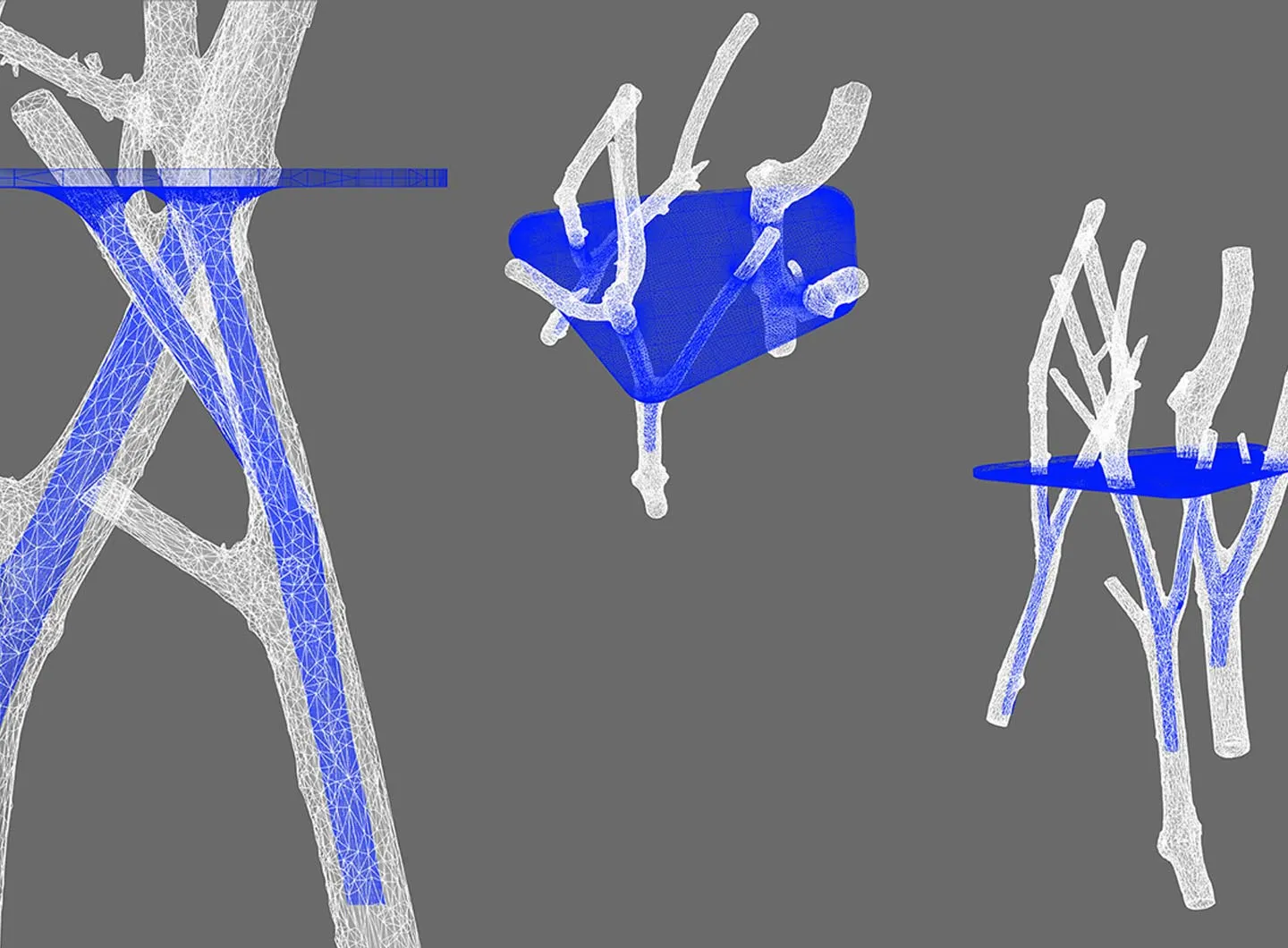

The proposal was pretty clear, i.e. talking about the schools but not in a self-referential way. We took a museum-style approach, creating a unique and homogenous display, based on the wide selection. All the projects are being exhibited as if they were museum pieces. There are no renderings or raw ideas, but existing three-dimensional prototypes to show the public what the proposals are really all about.

Who is it aimed at?

The Lost Graduation Show was devised for those young designers who are ready to make their market debut. Equally, the exhibition provides an opportunity for businesspeople, producers, designers, journalists and other design professionals, as well as the general public, to come and see the latest novelties in the realm of young design. Plus, after an 18-month halt, the exhibition is an invitation to re-establish an important dialogue centred on the future of design.

How did you come up with the installation?

The designers Camille Blin and Anthony Guex had a fantastic idea for the installation, they instantly understood the “supersalone” brief and looked for a sustainable material that could be ploughed back into the production cycle. We found Xella, which is an international producer of construction materials, who lent us 9,000 blocks of Ytong that we will then give back, all at zero cost and with a virtuous environmental impact. For those who can’t come to Milan, all the selected works will be exhibited on the Instagram platform @thelostgraduationshow. We really hope the digital presentation will also work as a recruitment opportunity for anybody wishing to make direct contact with the young designers.

How was the response to the open call for entries to The Lost Graduation Show?

We received 400 proposals, there are 170 objects designed and planned by around 200 students, from 22 countries and 48 schools. The ideas have come from Europe, Canada, the United States, Mexico, Qatar, Israel, Indonesia, India, Russia and Japan. All the design schools we contacted got back to us.

The strange thing is that so many projects respond to the same themes the world over. Is there a ‘collective of thought’?

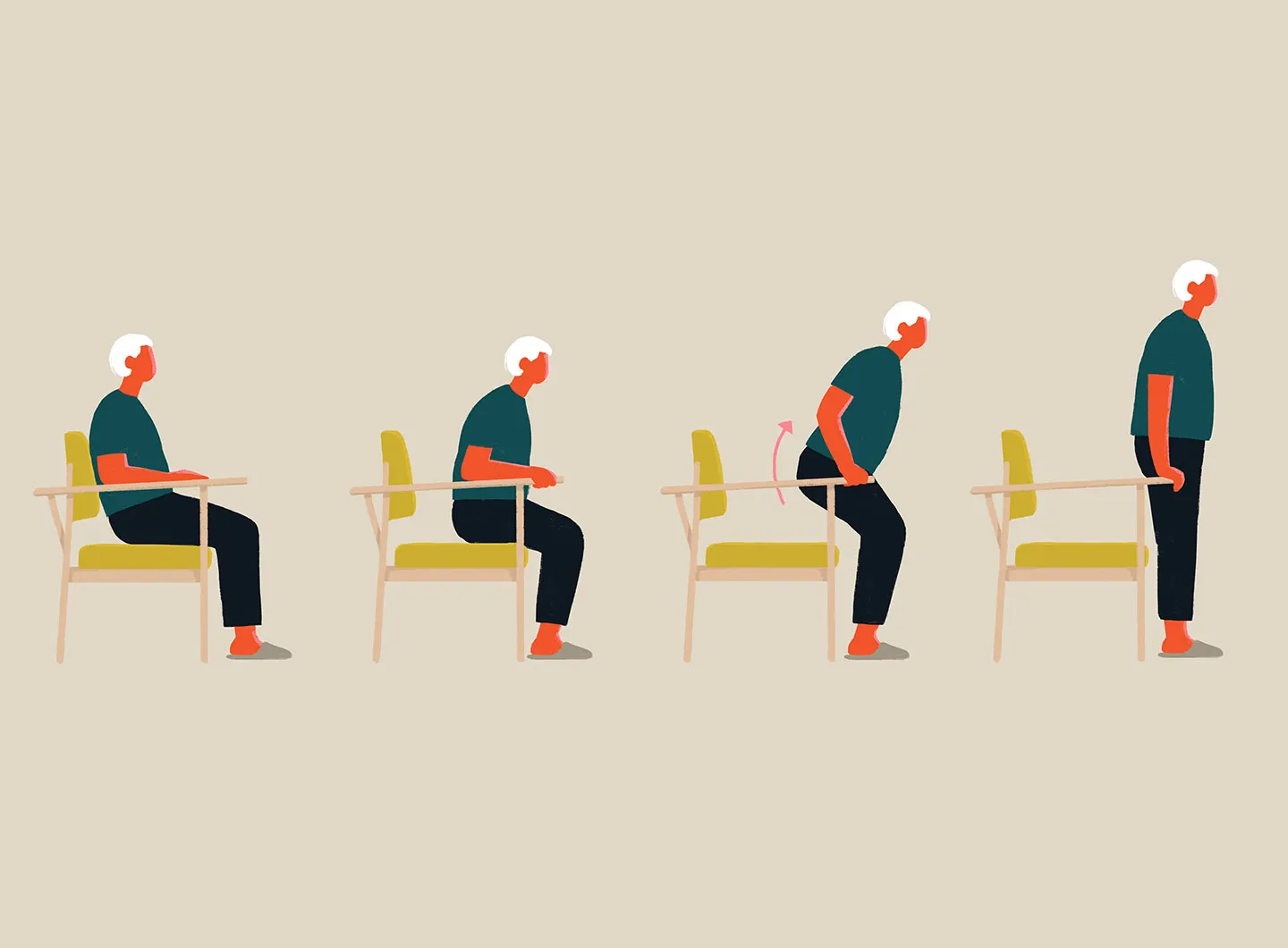

We are often used to labelling things - Italian design, Scandinavian design – but this time I felt that this was no longer appropriate and that it would make it hard to understand where certain projects came from. Many of the selected products are solutions to the same problems, many of the proposals are connected with medicine and wellbeing, rather than to a product type. The point isn’t the chair, rather a more universal and global theme with local and individual proposals.

There seems to be a very urgent need to solve the problems of today, in the face of those who say that the new generations are lost. What do you think?

Yes, there’s great urgency to solve today’s problems. Furthermore, if we look at these projects, I’d say that there’s a huge focus on production processes, on materials and on typologies. The interesting thing is that many young designers produce their projects in their own workshops and are inventing their own possibility of producing them; they are rediscovering the spirit of do-it-yourself, perhaps also due to the difficulties in breaking into the industrial world.

What is the role of design schools today?

Schools are fundamental for training students. They are places where they learn the tools of their future trade. But they are not abstract places. It is the teachers that help shape their thinking and their identities as designers. Teachers can have an enormous impact, comparable with the influence of the classic Master.

What can we take away from this exhibition?

I think this exhibition can act as a stimulus for the companies. Students can think freely and can rethink products, forms and production methods, even if it’s in an ingenuous way. Of course they then have to face up to reality, which can be stark. There’s competition, very stiff regulations, the constraints are mounting – companies should remember to believe in young people and be far-sighted enough to understand when an idea can be fielded. The exhibition is an invitation to producers to believe in the value of young people, allowing them to try things out, experiment and make mistakes.

Do people still dream of being designers these days? Is there still a desire to change the world?

Sometimes we underestimate what being a designer really means. The exhibiting students have got grit and desire, they have specialised and understood that it’s not just a matter of designing a new chair, rather of changing the system.

Branded residences: the market has tripled, so what are the opportunities?

The global race in figures: fashion, automotive and watchmaking join the hotel industry at the new frontier of exclusive living. Furniture brands also have a role to play

The Milan Design (Eco) System Working Groups are under way. Focus for 2025: the culture of design

The Salone del Mobile.Milano, in collaboration with the Design Department of the Politecnico di Milano, will launch the second edition of the Milan Design (Eco) System Working Groups on 25th September, providing an opportunity for institutions and industry experts to swap ideas and contribute to the 2025 edition of the Salone Annual Report