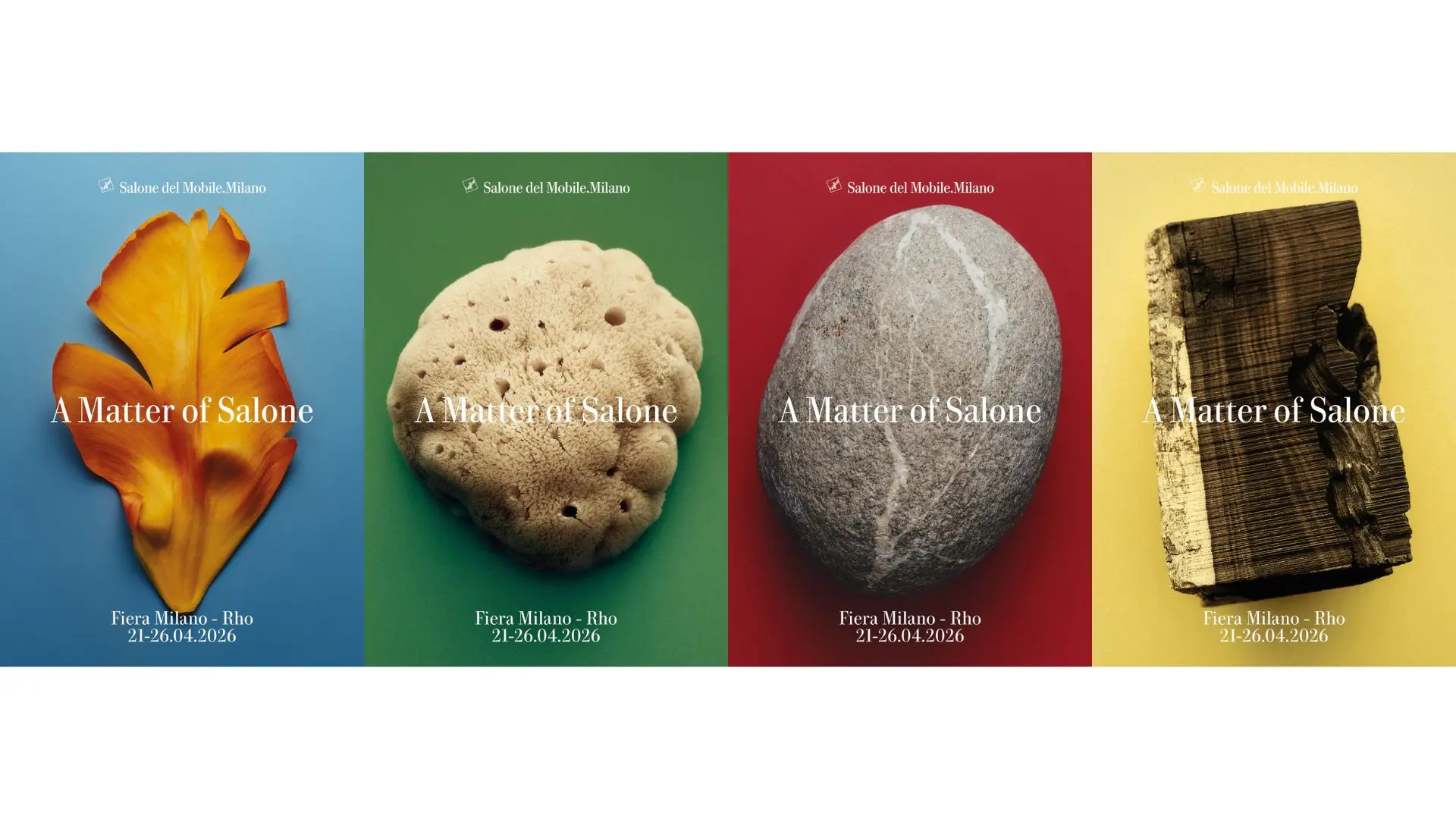

From a reflection on humans to matter as meaning: the new Salone communication campaign explores the physical and symbolic origins of design, a visual narration made up of different perspectives, united by a common idea of transformation and genesis

An archipelago pavilion for the summer in London’s Kensington Gardens

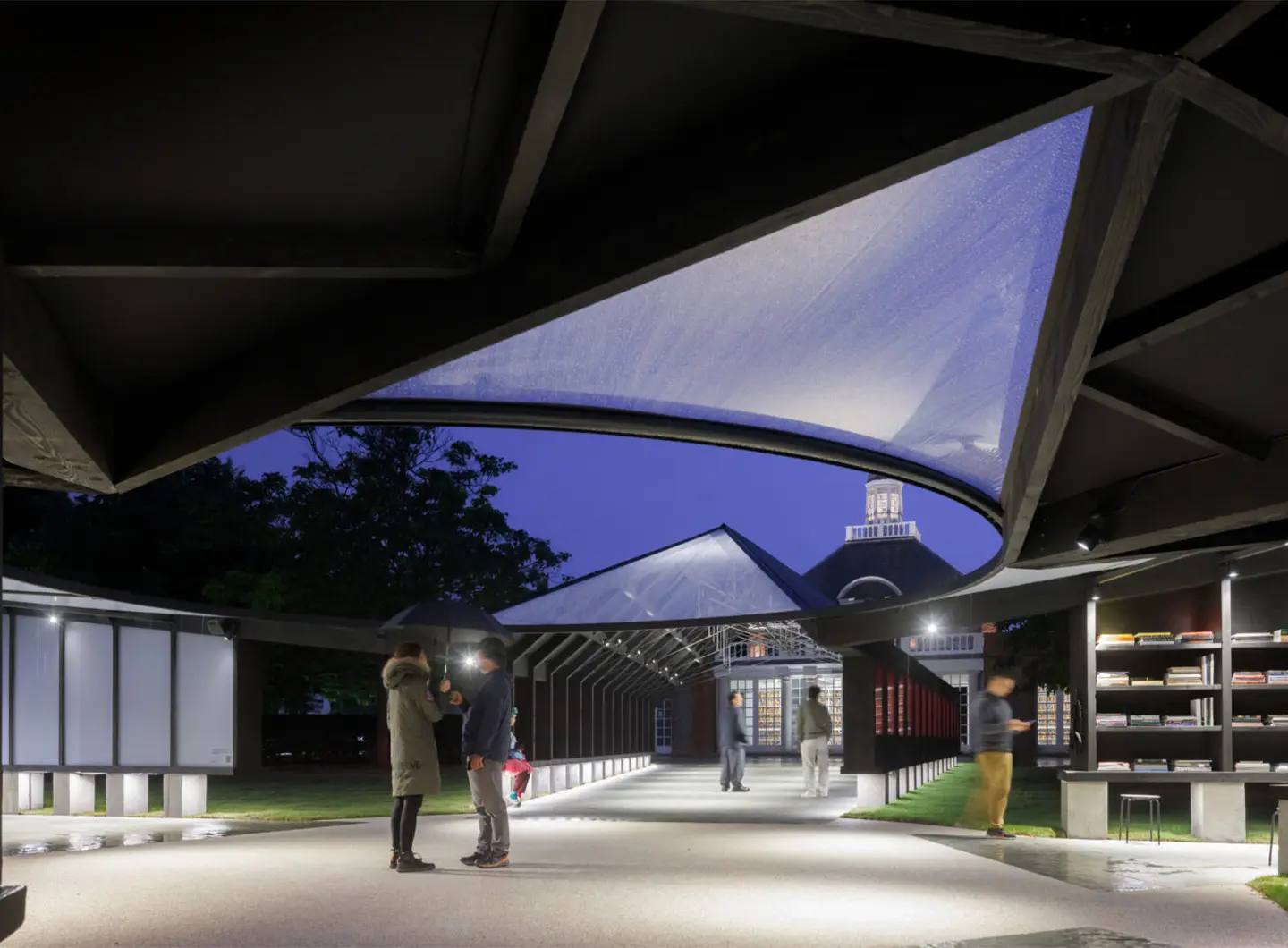

Serpentine Pavilion 2024, designed by Minsuk Cho - Ph. Iwan Baan

Designed by the Korean architect Minsuk Cho and his firm, the 23rd Serpentine Pavilion is comprised of five individual wooden structures, each with its own particular function. Evoking traditional Korean architecture, an open courtyard makes up the focal point of the building. In London, until 27th October this year

The compositional history of the annual Serpentine Pavilion – the temporary building that has hosted the public events promoted by London’s Serpentine since 2000 – was the starting point for the project by the Korean architect Minsuk Cho and his Mass Studies. Tackling his prestigious commission, assigned annually to emerging designers of international renown that have yet to complete a project in the United Kingdom, Minsuk Cho was aware of a “spatial preference” expressed more than once by colleagues that had preceded him.

The Serpentine Pavilion 2024, designed by Minsuk Cho and Mass Studies

From the late Zaha Hadid, the architect responsible for the inaugural pavilion in this pioneering venture which has inspired similar initiatives across the world, to À table, a call to come together at the table and share a meal, (the Serpentine Pavilion 2023, designed by the French-Lebanese architect Lina Ghotmeh), the pavilion has often been conceived as a single structure - porous, reflective, pneumatic, compact, and one edition was even partially underground – situated in the centre of the Serpentine South lawn. Minsuk Cho has been at the helm of his firm since 2003, with projects such as the restoration and enlargement of the French Embassy in Seoul (2023) and the Korea Pavilion at Expo 2010 Shanghai under his belt, but in his Archipelagic Void he allows the empty space to occupy the epicentre of the pavilion and the site of the intervention. Referencing Korean houses of the past, in which the courtyard (madang) also used for individual and communal activities, served as an element connecting different residential areas, the pavilion identifies its fulcrum and pole of origin in this central void. The pavilion’s five (predominantly wooden) “islands” radiate from here: like darts, these micro-architectures each shoot out in an autonomous functional direction, acquiring a specific name. Until 27th October, The Willow, a six-channel sound installation, can be listened to in the Gallery; there’s a chance to take part in the collective artistic project The Library of Unread Books (curated by the artist Heman Chong and the archivist Renée Staal) by contributing a book unread by its donor. There’s an opportunity to interact with the pyramid structure of the Play Tower by literally climbing up it, and to relax and chat in the Tea House and in the Auditorium, the main performance and gathering area.

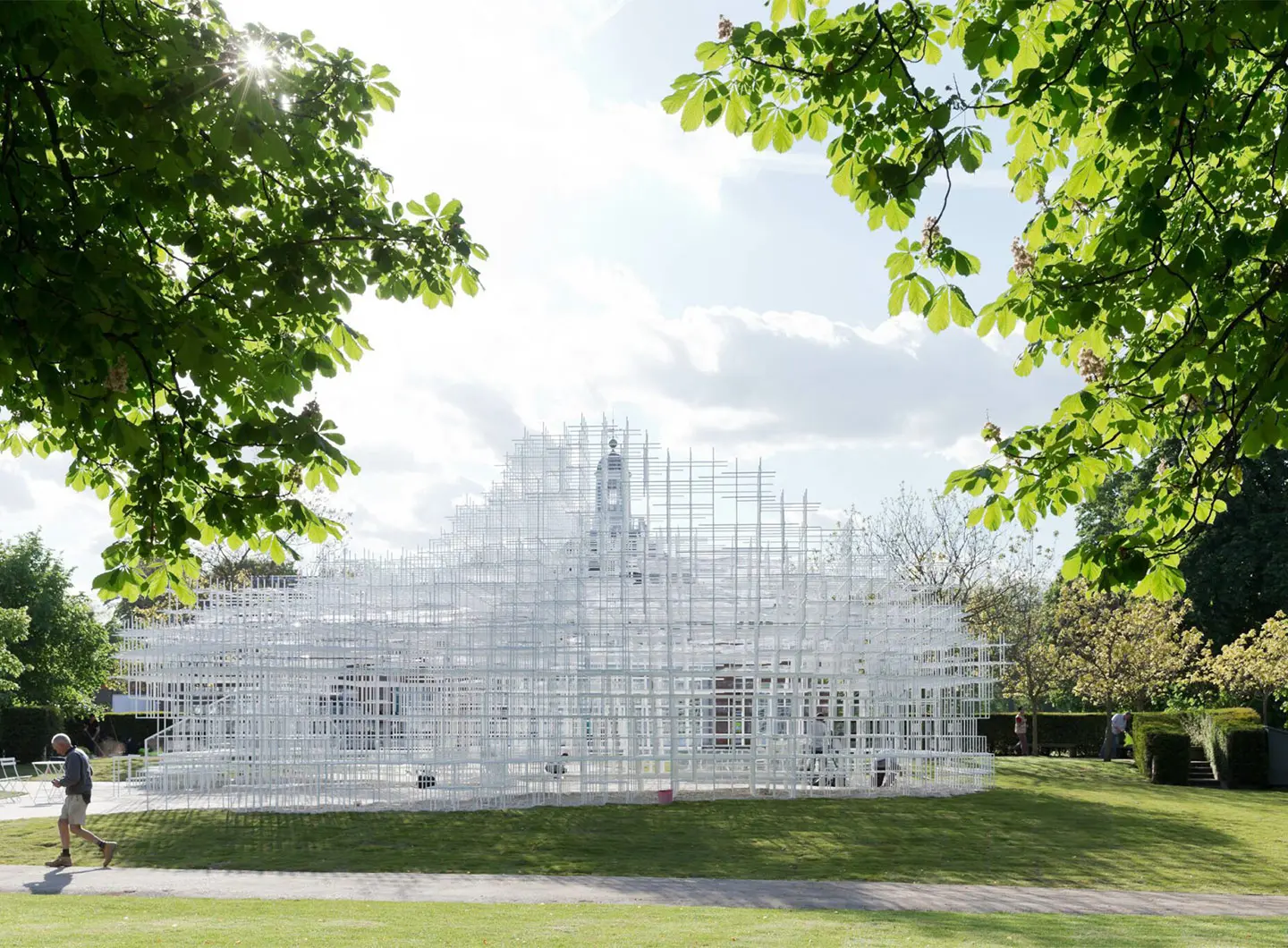

The architects who built the history of the Serpentine Pavilion, from 2000 to today

The first event in the programme (on 7th June, the opening day) will feature Minsuk Cho in conversation with the Artistic Director of the Serpentine Hans Ulrich Obrist and other key figures about the successful Serpentine Pavilion project. With its 25th edition fast approaching, the pavilion continues to exert its powers of attraction over the architectural community, whilst also bringing in non-professionals with its wide-ranging programme of events. Retracing the “roll of honour” of this project allows us to identify the trajectories, urgencies and experiments across the last two decades of global architectural practice – from the growing interest in the themes of reuse in construction materials to the desire to introduce memories of distant places, often far off the more frequently beaten tracks, into the London context to the decision to convey messages of a social nature while leveraging the expressive powers of an albeit temporary building. These days, the assignation of this commission is seen as career-changing and a tremendous boost to the reputations of the designers selected. Despite the heterogeneity of their vision, Zaha Hadid, Daniel Libeskind, Toyo Ito, Oscar Niemeyer, Álvaro Siza and Eduardo Souto de Moura, Rem Koolhaas, Olafur Eliasson, Frank Gehry, SANAA, Jean Nouvel, Peter Zumthor, Herzog & de Meuron and Ai Weiwei (the designers from 2000 to 2012) are globally considered to be among the great masters of their respective fields of discipline. The ability of this initiative to spot talented designers has continued throughout the last decade, as confirmed by the professional ascents of Sou Fujimoto (2013), Bjarke Ingels (2016), Diébédo Francis Kéré (selected in 2017, awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize 2022), Frida Escobedo (2018), Junya Ishigami (2019), Sumayya Vally (2021) and Lina Ghotmeh (2023).

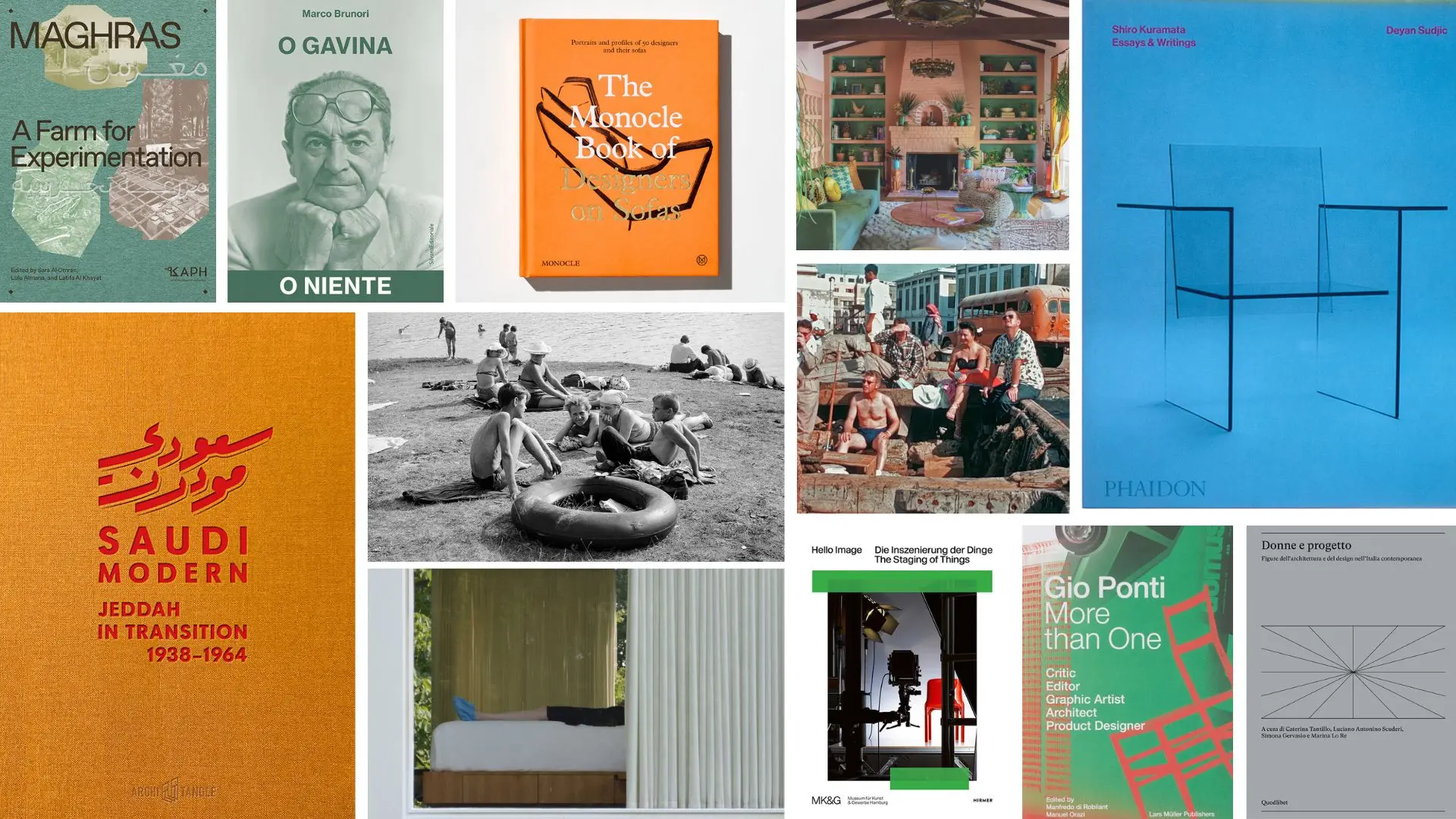

Salone Selection

Salone Selection