The furniture and design segment dedicated to life en plein air. Interview with Roberto Pompa of the Assarredo Presidential Council as well as President of Roda

From Arne Jacobsen to Elmgreen and Dragset: Danish Diaries by Marco Sammicheli

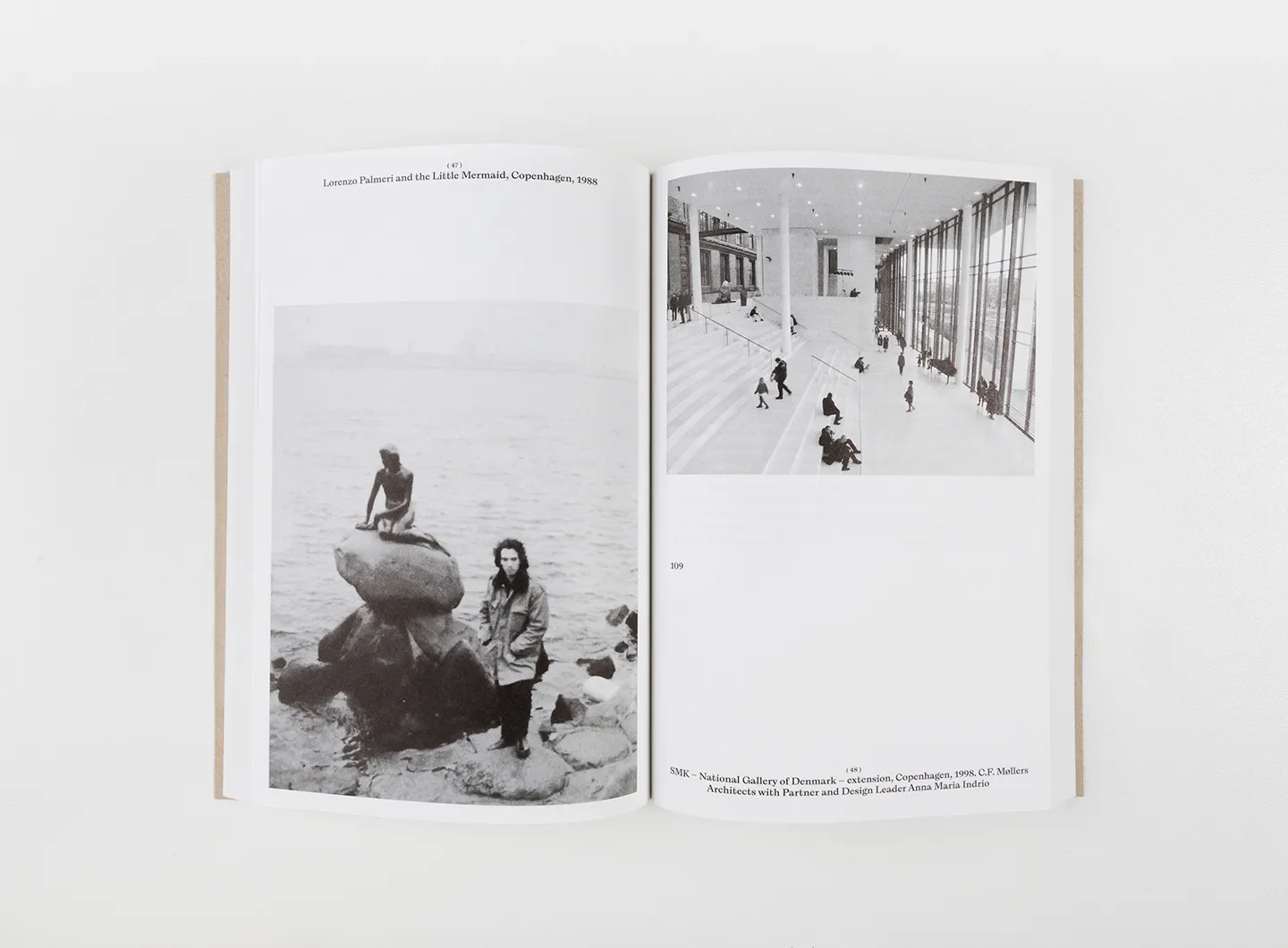

SMK – National Gallery of Denmark – extension, Copenhagen, 1998. C.F. Møllers Architects with Partner and Design Leader Anna Maria Indrio

An autobiographical journey described in a new book by the Director of the Triennale Milano Italian Design Museum intersects with the visions of artists, architects and writers who were both creative and bold

“While I could not fully understand my relatives and friends, I could certainly make up for it by studying the artists, architects, writers, intellectuals and professionals who for almost a century have shuttled back and forth between Italy and Denmark.” This is how the introduction to the fascinating Danish Diaries begins – just published by Humboldt Books. Its author confesses not only his partial understanding of the Danish language but goes much further by asserting that “even now my spoken Danish is nil.” Marco Sammicheli – Director of the Triennale Milano Italian Design Museum, an institution for which he is also curator of the design, fashion and crafts section – has made a virtue out of necessity. To overcome his linguistic frustrations, he has given into to his fertile imagination and given himself over to research and study, drawing a common thread between all those people who, as he now does, split their time between Italy and Denmark during the second half of the 19th century. “It is a regular and well-distributed migration, one which is not just concentrated in large urban centres or the main provinces – on the contrary, the opportunities and uniqueness of certain conditions have brought the Danish community to spread throughout Italy.” The same goes, in the opposite direction, for Italians in Denmark.

The book is educational, telling the behind-the-scenes stories of important and significant lives. He starts with Thorvaldsen – Canova’s great rival, who arrived in Rome from his native Copenhagen in 1797, where he remained for over 40 years and where “every year, on 8 March, he organised a party to celebrate his ‘Roman Birthday’” – and ends with Eugenio Barba, a theatre director from Gallipoli, who set up the historic Odin Teatret in Norway and subsequently moved to Denmark with his troupe. The book contains a lot of interesting information, perhaps known only to professionals – such as the fact that the first publishing house in Italy to celebrate Arne Jacobsen was Adriano Olivetti’s Edizioni di Comunità, the primacy of architects, that between 1875 and 1925 Danish travellers were the keenest on Italy as a destination, and the story of Vico Magistretti which is intertwined with Denmark. The key to cultural relationships between Italy and Denmark turns out to be “this common imagery, made up of elements that are so far apart but held together by harmony,” says Sammicheli.

Danish Diaries, Humboldt Books

It was actually falling in love. Since then Denmark has become the exotic place to explore, the island to discover and the enigma to decipher. I’ve listened to the language for almost 20 years without fully understanding it and every time I’ve tried to bridge that gap by studying and combing museums, libraries, houses, shops, stations, fairs and ports. All the protagonists of the book came into my life thanks to my stubborn attitude towards meeting people, relationships and dialogue. Even when I couldn’t meet the people myself, I tried to get to know them by collecting as many memories as possible.

Because there are biographical notes, pieces of the lives of brave men and women who sought a new existential challenge in other, different things. They all shared an urgent need to channel their creativity, which informed their expressivity: theatre, communication, art, design, fashion, publishing. Constant translating, interpreting and hybridisation to nurture projects that lifted reality. The diary contains stories of success, of approaches, of failures, of pauses, but every single one exemplifies resourceful energy, a work ethic, hard-working commitment.

Danish Diaries, Humboldt Books

I come from the Marches, I was born beside the sea listening to the Sienese stories of a grandfather I wasn’t in time to get to know. Then I went back to Siena to do my degree. Then there was Germany, Brazil, Chile and then flitting between Denmark and Italy; it’s the care over natural and artificial light in an interior; it’s a frugal meal of black bread, butter and potatoes; it’s climbing off a pier and diving into the sea; it’s the comfort of spare, timeless design.

They share an obsession with quality. Furnishing, food, architecture and music are four excellent things that both countries set a maniacal store by. The work culture that creates domestic landscapes and forms of entertainment is fervid and skilfully cultivated. There are lots of differences, but in the field of the creative industries alone there is one thing: Italy creates fashions, Denmark follows them, adopts them and reformulates them.

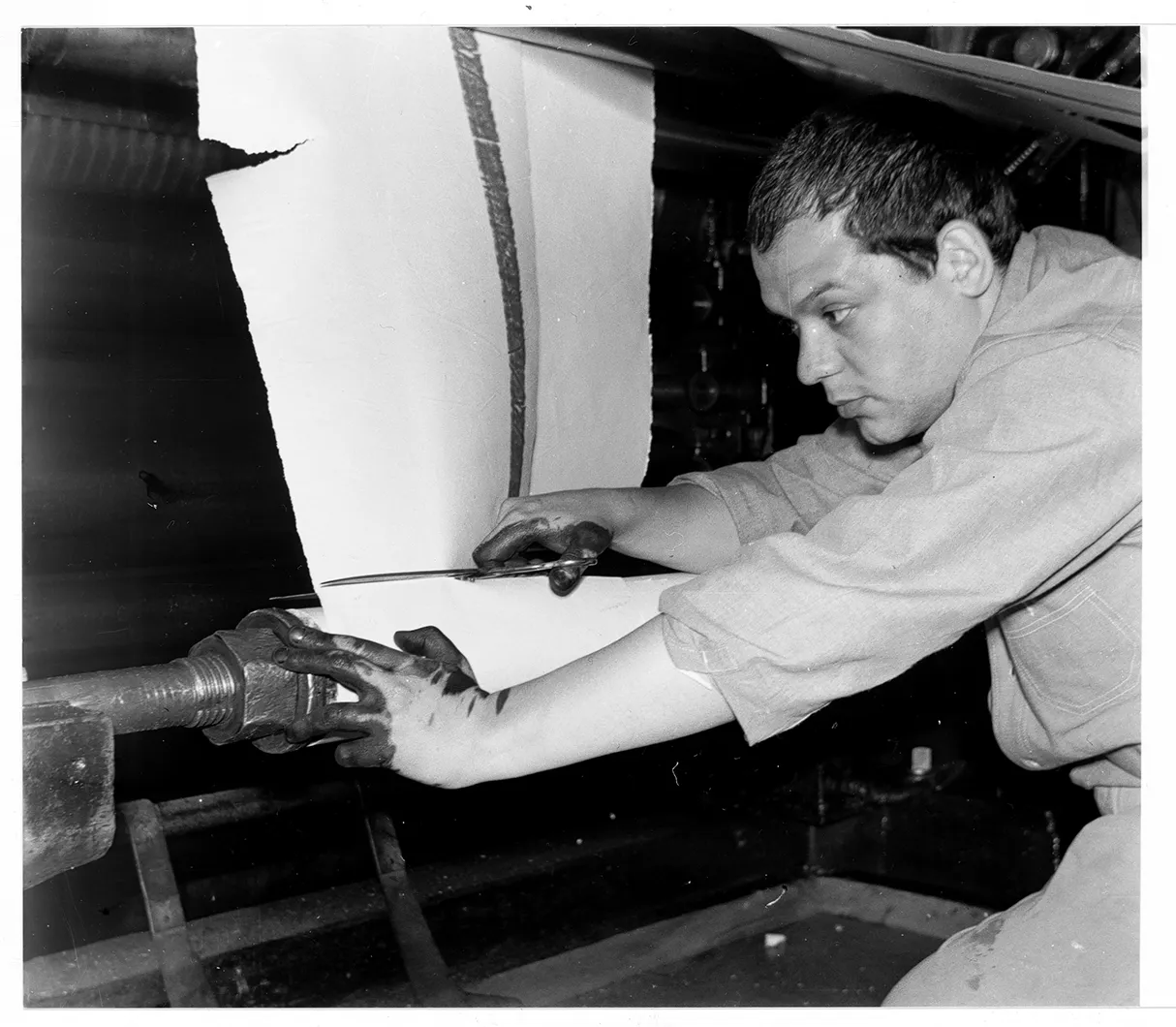

Vico Magistretti and Maddalena De Padova, courtesy Archivio Storico De Padova, Milano

Design is a field that both countries have in common; it’s a competitive arena around which business and obsessions gravitate. They both have a network of schools, businesses, studios, bodies that have been working to develop a discipline for the last century, and its impact on daily life remains extremely powerful. It’s a field in which the dialogue between creatives has gone on uninterruptedly for the last half century with leading figures such as Vico Magistretti, Verner Panton, Arne Jacobsen, Bruno Munari, Mikal Harrsen, Anna Maria Indrio and Maddalena De Padova.

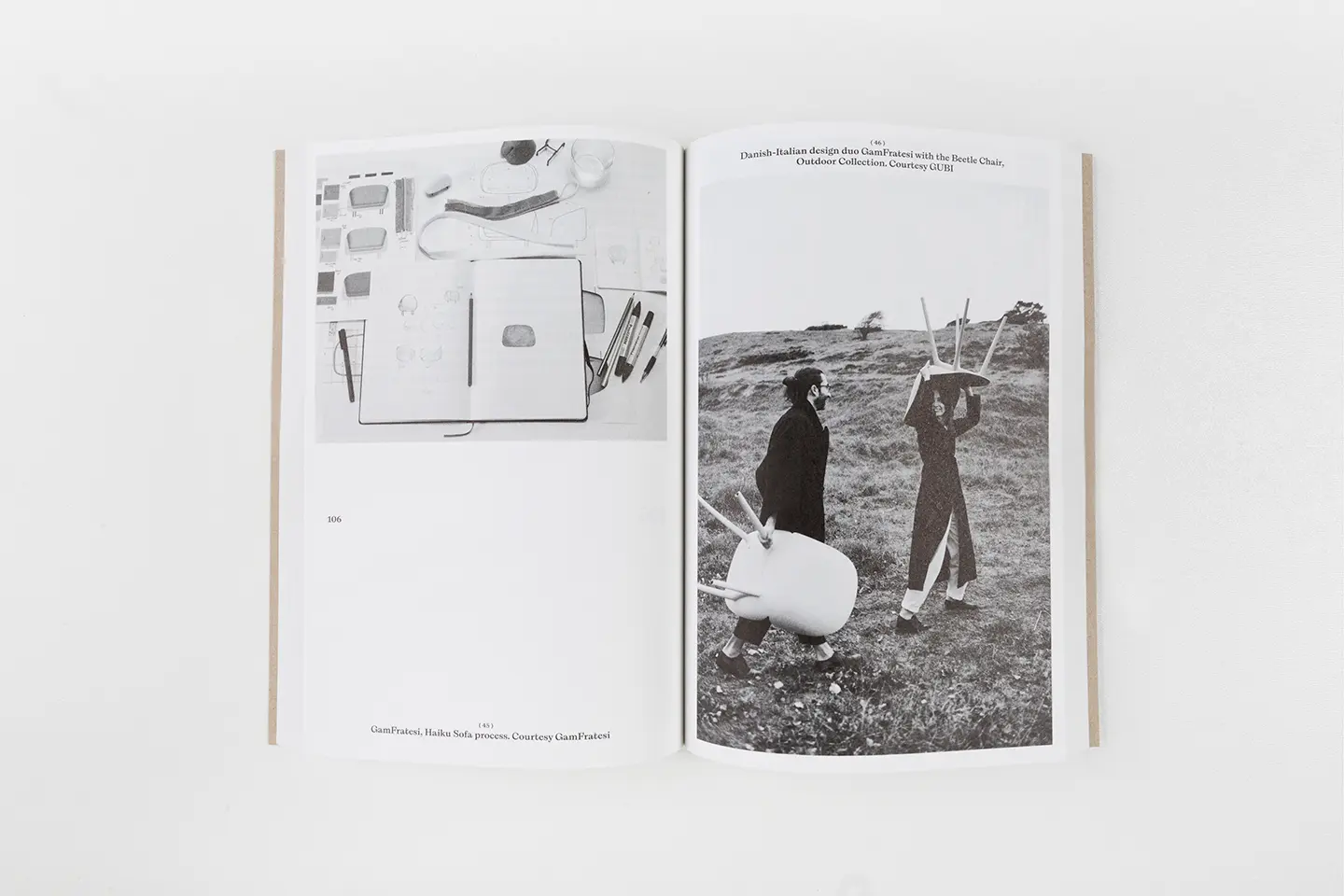

I feel close to those who have brought their lives and professions, sacrifices and visions, drivers and reflections together through their life as a couple. Of all of them, GamFratesi, Stine Gam and Enrico Fratesi, are undoubtedly among the most closely bound-up with the poetics of this book. But not just them – there are the Olders, Alessandro Sarfatti, Noona Smith-Petersen, Elmgreen and Dragset.

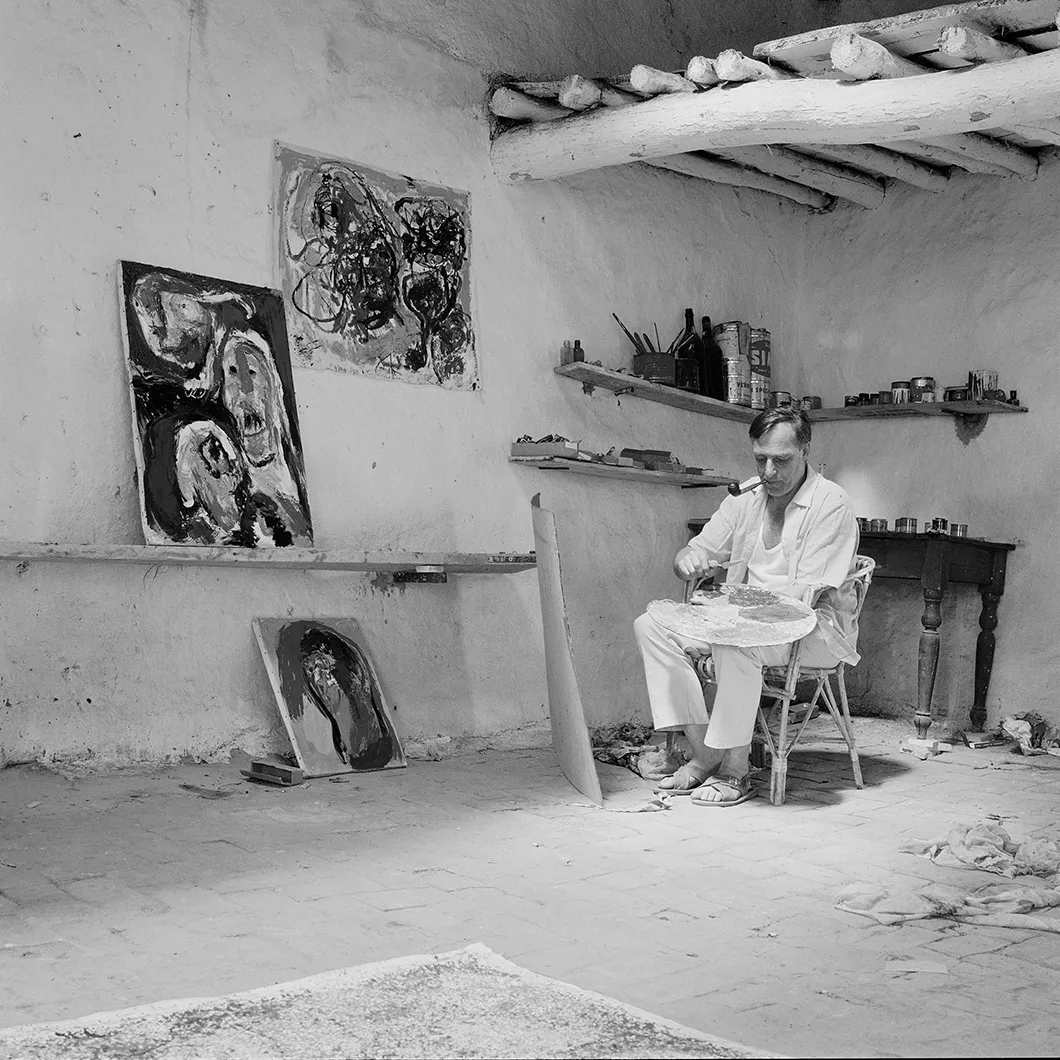

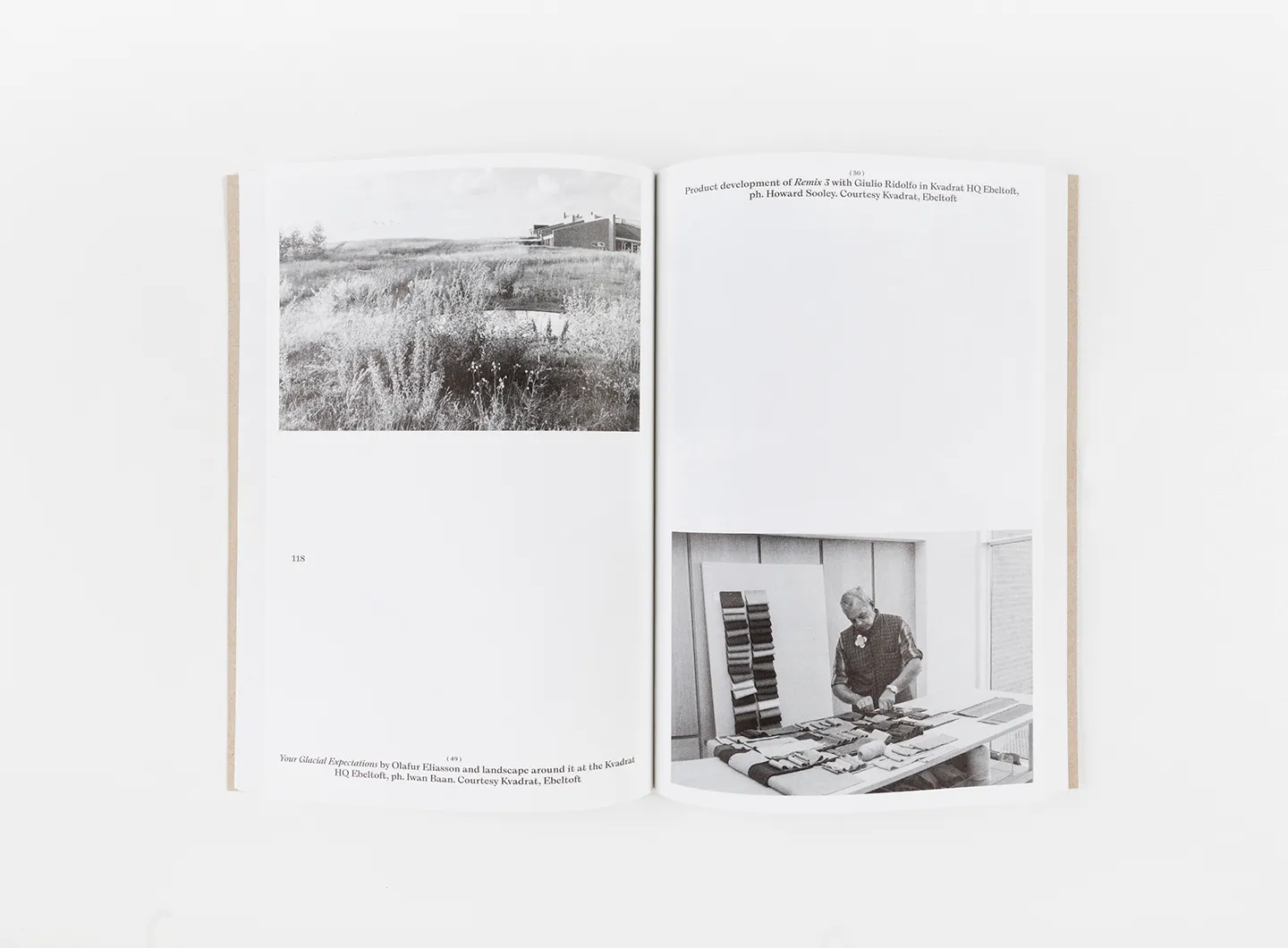

Allowing yourself to be caught up in the courageous stories of extraordinary creators such as Giulio Ridolfo and Asger Jorn. The former took Friuli through the warp and weft of Kvadrat textiles; the latter found his second youth in Liguria. To believe in the handing-down of generational entrepreneurial dynasties such as the Byriels, the Graversens, the Gubsis, the Lodigianis, the Olivettis, the Orsinis. To carry on believing in a Europe with good will stretching from Amalfi to Århus. To remember Piero Manzoni and Bertel Thorvaldsen … but that’s already a fourth good reason.