A little more than a month before the opening of "Red in Progress. Salone del Mobile.Milano meets Riyadh", the Salone del Mobile.Milano’s event in Saudi Arabia, the celebrated architect and designer explained to us what the Business Lounge he has designed for the occasion will look like, and what stories its interior will tell about Italian design

Ben van Berkel, UNStudio

©Inga Powilleit - Courtesy of Alessi

The architect who wants to improve people's quality of life, producing architecture, urban infrastructures and adaptive, resilient and future-proof objects

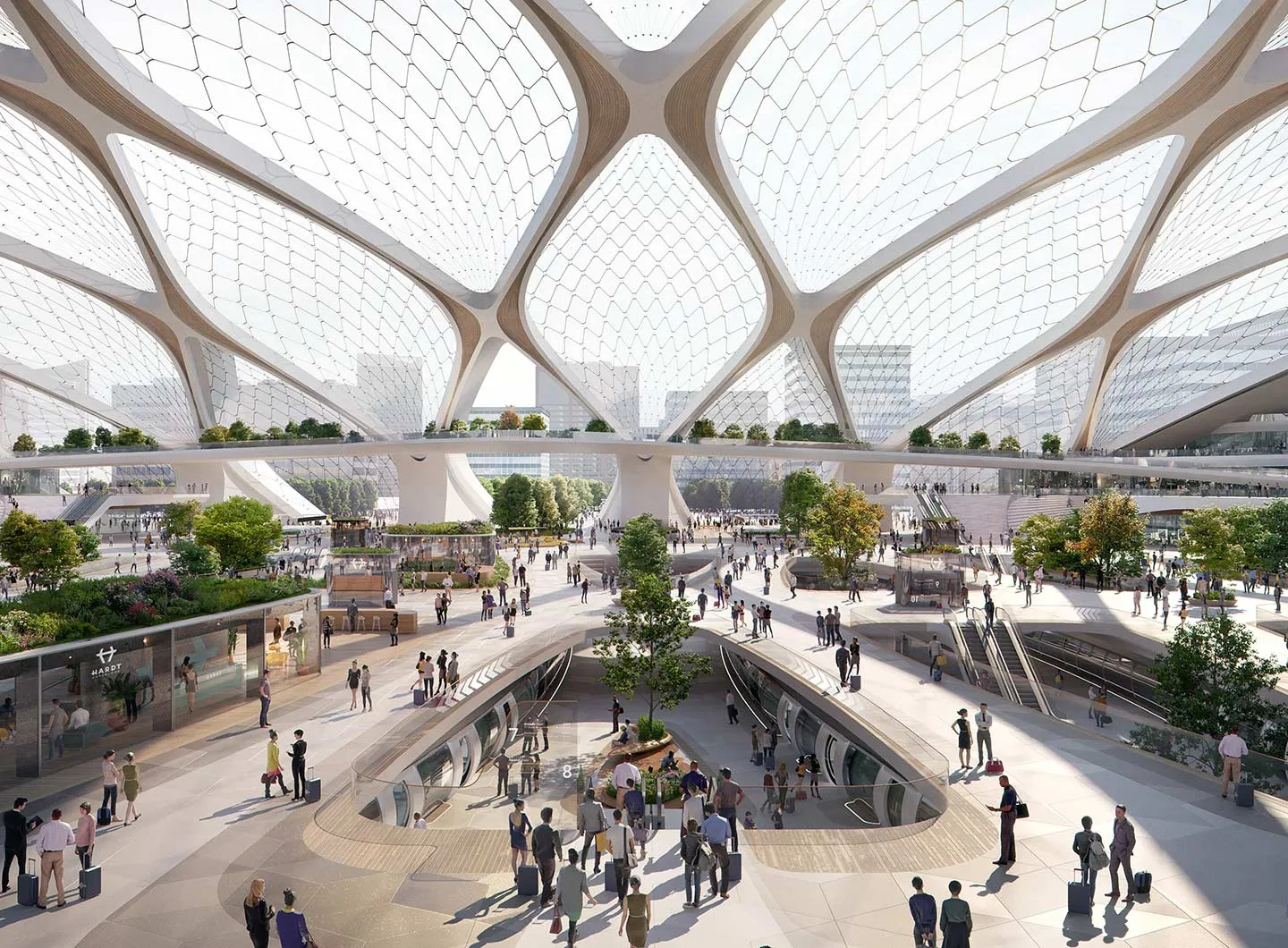

The Dutch architect Ben van Berkel graduated from the AA in London in 1987, setting up UNStudio with Caroline Bos in 1988. It instantly became a hive for specialists in the architectural, urban development and infrastructures sectors. The practice has many iconic projects under its belt, including the Mercedes-Benz Museum in Stuttgart, Arnhem Centraal railway station in the Netherlands, the Moebius House, and the University of Technology and Design in Singapore. But that’s not all. During its thirty years, it has grown to include other disciplines, from architecture to urban planning and design, becoming a real design giant, setting up dozens of worksites in three continents, four international branches - Amsterdam, Shanghai, Hong Kong and Frankfurt – employing over 200 highly qualified professionals from 27 countries, and clocking up more than a hundred awards and recognitions.

The common thread running through all UNStudio’s projects – and their starting point – is research geared to improving the quality of life of people all over the world. The aim is to produce buildings, urban developments and infrastructures, user-centric objects and products that are adaptable, resilient and future-proof, whatever may come to pass. The side of design that most interests Ben van Berkel is closely bound up with human relations, the interaction between citizens and space, its fruition and physical experience. Man at the centre of design. This is why the architect describes his work as transformative, carrying out projects that interact organically with the public.

Another fundamental characteristic of the studio’s work is the promotion and practice of sustainable design. Environmental issues and social sustainability are taken into consideration right from the off. The ultimate goal is the health of the planet, which entails upholding and promoting the circular economy, energy transition, water self-supply and recycling. What’s more, their kind of design is practicable because it is both financially and socially viable.

The common language for expressing this design vision consists of an alphabet of plastic, fleeting volumes, ribbon elements and dynamic surfaces that put metal and colour together to produce adaptive architectural typologies for a constantly changing society.

We talked to Ben van Berkel, who recently held the Kenzo Tange Visiting Professorship at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, about ideal cities, new ways of living space, resilience, technological innovation and design as a political practice. We talked about children too.

Every project presents new challenges, but some take you on more of an emotional roller-coaster ride than others. Although it is part of the profession and you get used to it over time, not having your design selected in a competition is particularly tough on the whole team. In competitions, we work day and night to meet the tight deadlines, so it is always a disappointment if the design - which you truly hope matches the client’s vision and needs - is not selected. In contrast, when you win, it’s a great feeling that your vision truly connected with that of the client. Similarly, if a project is stopped - which can be for a multitude of reasons that are completely beyond your control – the disappointment is of course enormous. It truly can be very emotional. In contrast, it’s a fantastic feeling when you see a project – that you have worked on from the first sketch to the supervision of the very last detail – becoming operational; when you see how it works and how people interact with it. That is what every architect works towards. That is the best reward for the immense dedication that everybody puts into this work. But I can’t really single out specific projects in this context. They are all so different; all present their own challenges and emotional highs and lows. But over the years, I have learnt to approach my work in a serial way, to look back at certain qualities in different projects and see where they share a particular set of ideas, solutions, conceptual and formal qualities and try to expand on these in future work.

Our mission is to produce people-centric designs that are adaptive, resilient, healthy and future-proof, but we also very much believe in an integral approach; in design solutions that holistically tackle organisational, sustainable, formal, material and conceptual challenges. The name of our practice, UNStudio, means United Network Studio. This is because we firmly believe in working with experts from other fields and that we, as architects and designers, are just one actor within this broader network. Recently however, technology has become extremely important to the built environment, which is why in 2018 I also founded the arch-tech company UNSense. UNSense aims to make a difference in the intersection between technology and the built environment.

Being resilient means being able to recover quickly from any change that may have a negative effect. In terms of architecture, this means that we have to design with such recovery in mind from the outset. This can mean incorporating a flexible floorplan that can enable change of use in an economic downturn, housing crisis, or as a result of changing trends (such as new ways of working or living), but it can also mean designing a facade system that can easily be updated in the future to prolong the lifespan of the building. However, with the future now changing faster than ever before, even the most accurate predictions can become redundant by something like a sudden advance in technology. To be able to navigate through these changes, architects and designers have to design with flexibility in mind, because in order to be resilient, architecture has to be adaptive, if it is to be able to meet the ever-evolving needs of society.

The ideal city is a healthy city, in every sense. It not only enables healthy economic systems, but alongside reducing its carbon footprint and maintaining the health of the planet, it also ensures the physical, mental and social health of its inhabitants.

I certainly view architecture and design as political practices, and not merely the product of political influences. Anything that plays a role in shaping society, that can affect people’s welfare, is intrinsically political. I don’t mean this in the sense of activism, but more in terms of how design can affect and shape our daily lives. There is also a great deal of responsibility attached to this.

Initially our Knowledge Platforms were set up to share practice-related knowledge, share ideas and exchange knowledge - both in-house and with external collaborators on R&D projects. However, in the intervening years this has evolved into two separate units. One, UNSFutures, focuses on forecasting and designing future scenarios. It turns knowledge into tangible designs that move projects forward from concept development through to design implementation. To do this, the unit works closely with cross-disciplinary teams of academics, technologists and design leaders, as well as with the designers at UNStudio. The second and most recently established unit is UNSx and is tasked with designing for the shared human experience. It is set up as a think-tank and experience lab to devise products, services and strategies that push the boundaries of what is possible in the way we live, work and play. This unit consists of a team of architects, computational designers, product designers, creative strategists, VR/AR specialists and sustainability consultants.

I’m looking forward to improving the analogue world with digital technologies. For architects, designers and urban planners, technology can be used as a tool to improve the built environment; to shape it around the actual needs of the end-users and make our buildings and cities more healthy, resilient and sustainable. Technology in architecture is primarily related to new efficiency models. For example, we now have sensor technology that allows us to understand the performance of buildings, meaning that today architects can design with data. These sensor technologies can bring architects closer to the users of their buildings, discovering what they need, what they enjoy and what kind of flexibility they require. This is why we founded UNSense, where we implement technology to create better human-centric spaces. But unlike the more common smart city concepts, UNSense pushes beyond mere efficiency and performance-related goals, instead designing for positive human, societal and environmental impact. We believe that such considerations should always guide the development and implementation of technological solutions.

Throughout history, pandemics have changed cities in different ways, such as the Black Death in the 16th century, Cholera in the 19th and Spanish fever in the 20th. Whether it was the introduction of underground sewage systems, or planning regulations that limited the density and height of buildings, as happened in New York, in order to ensure good air circulation and daylight conditions on the city’s streets. But we believe that the 1,5 meter society is a temporary condition. In design terms, it’s not about facilitating a 1,5 meter society in the long run. We all have to be very careful not to rush ideas, or draw simple conclusions. Instead, we have to look very closely at what the real issues are and find long-term solutions to these. At UNStudio we see it as an opportunity to improve our integral approach to a topic that we have been working with closely for some years now: making our indoor and outdoor environments healthier. This includes such concerns as creating more space where density is high, or improving air quality, ventilation, acoustics and daylight in buildings, in order to reduce sick leave. An integral approach means that we don’t focus on one issue alone, we instead look for holistic solutions. So if we look at what we have learnt from this pandemic, we include that in a bigger picture, or in group of measures to improve how we live and work. So the pandemic has made it clear to architects that they need to focus even more closely on the possible ways that design can help to prevent illness and keep people physically, mentally and socially healthy. It has added new parameters and placed renewed emphasis on how important a people-centric approach is in design.

We have been working on product designs for Alessi for over 15 years and have designed a wide range of products, from a Tea and Coffee Set, to a wine rack, cutlery and even a truffle slicer. But the Kid’s collection came about as a result of observations I made while playing with my son. I have always enjoyed the playfulness of how children perceive and explore the world around them; how the scope of their imagination allows them to think beyond rational boundaries, and how this liberation from logic enables the most creative and wonderfully irrational ideas and perceptions. This is often coupled with intense curiosity, as they try to understand where their imagination ends and the ‘adult world’ begins. My son, who is now 4, has reached this stage; he wants to know if Superman can really fly? If we can lift up a house? If we could go to South America today? Trying to grasp this kind of mindset stimulates your own creativity as a designer and you have to keep it very much in mind when you design for children. Basically you want to enrich the imagination and stimulate playfulness and curiosity, because then a kind of learning experience can be created. It has actually been a very interesting experience. When you design a product for adults, you concentrate on its functionality and how to couple that with its materiality, with its aesthetic and spatial qualities. But something else happens when you design for children: different, more playful ideas start to rise to the surface, because you start to approach the design through the mind of a child. How do children experience objects, shapes, textures and colours? How will this product stimulate the child's imagination? Or how could you improve the design to encourage play, learning and creativity? You are faced with a whole new world of possibilities, but in the end, it depends very much on the actual product and what it is for. So for each one, you have a different focus, and you try to really hone in on that.