Pure volumes, minimal or non-existent decoration, primacy of functionality, harnessing new materials: from the Casa del Fascio in Como to the railway station in Florence, the story of an experimental period that, after almost a century and several attempts at damnatio memoriae, remains a tangible presence in Italy.

Denis Curti talks about Efrem Raimondi

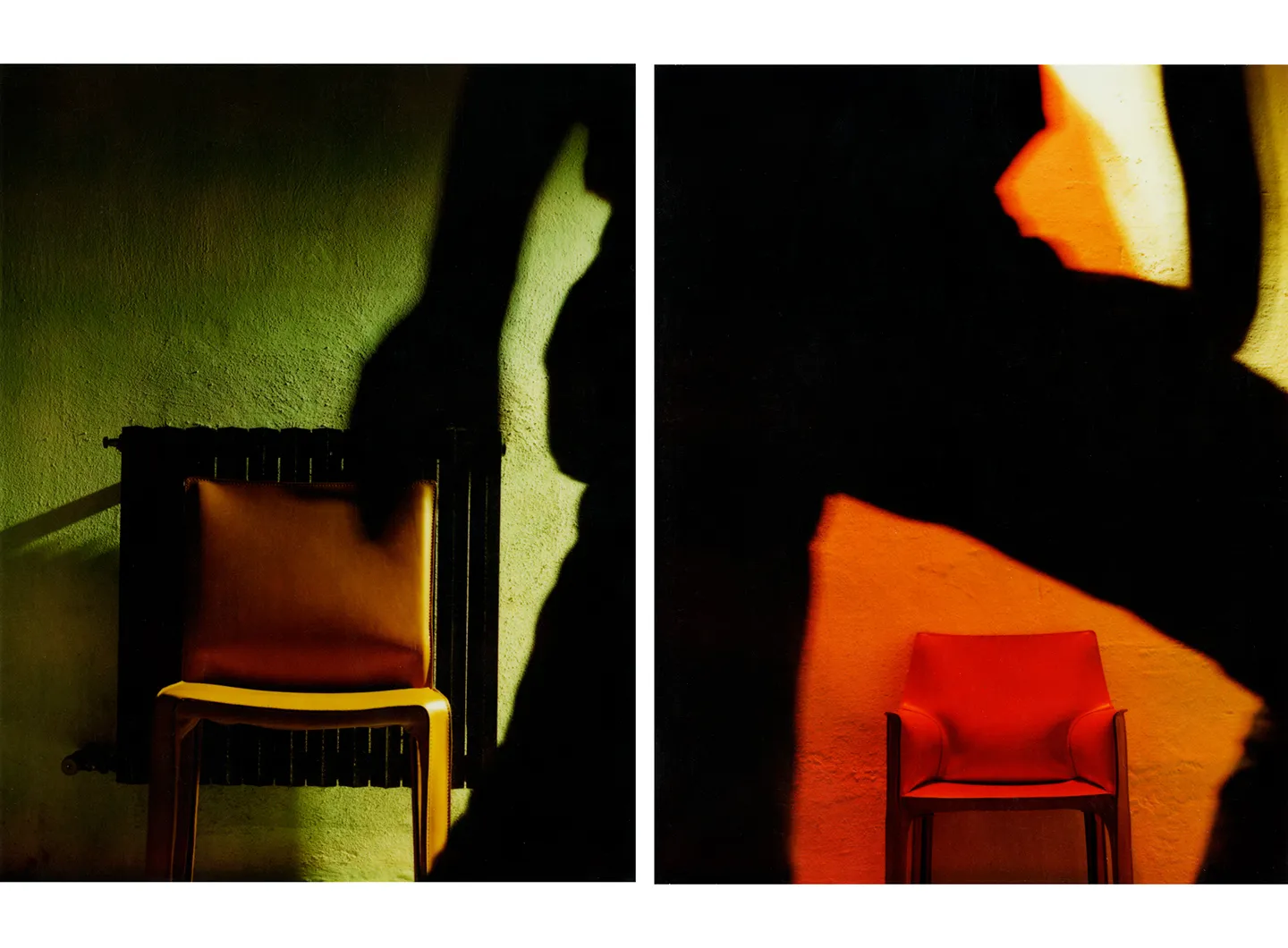

Catalogo Campeggi, 2007

A conversation with Denis Curti, director of the Master’s in Photography at Raffles Milano and curator of the exhibition Quintessenze, on at the same time as “supersalone.”

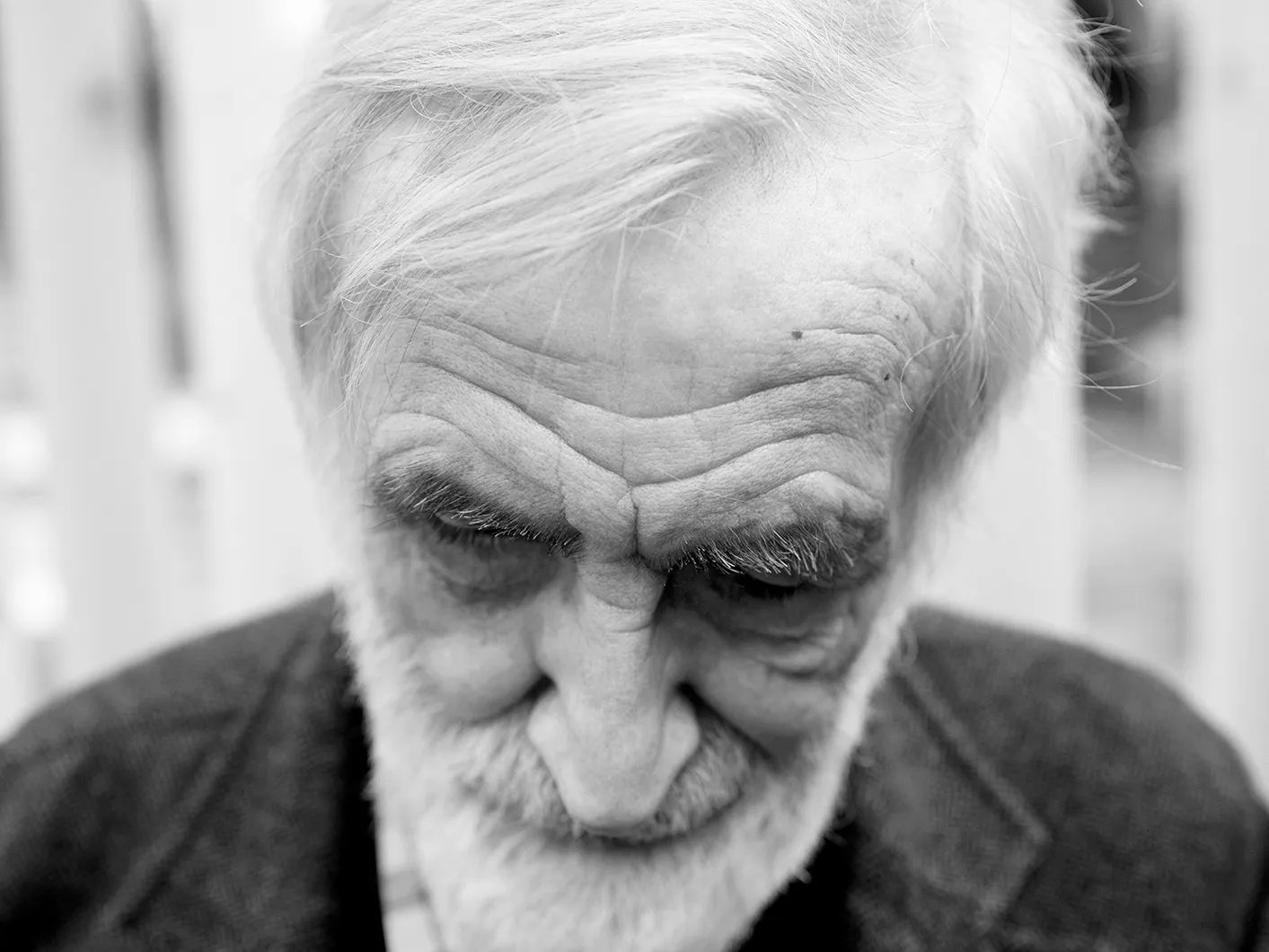

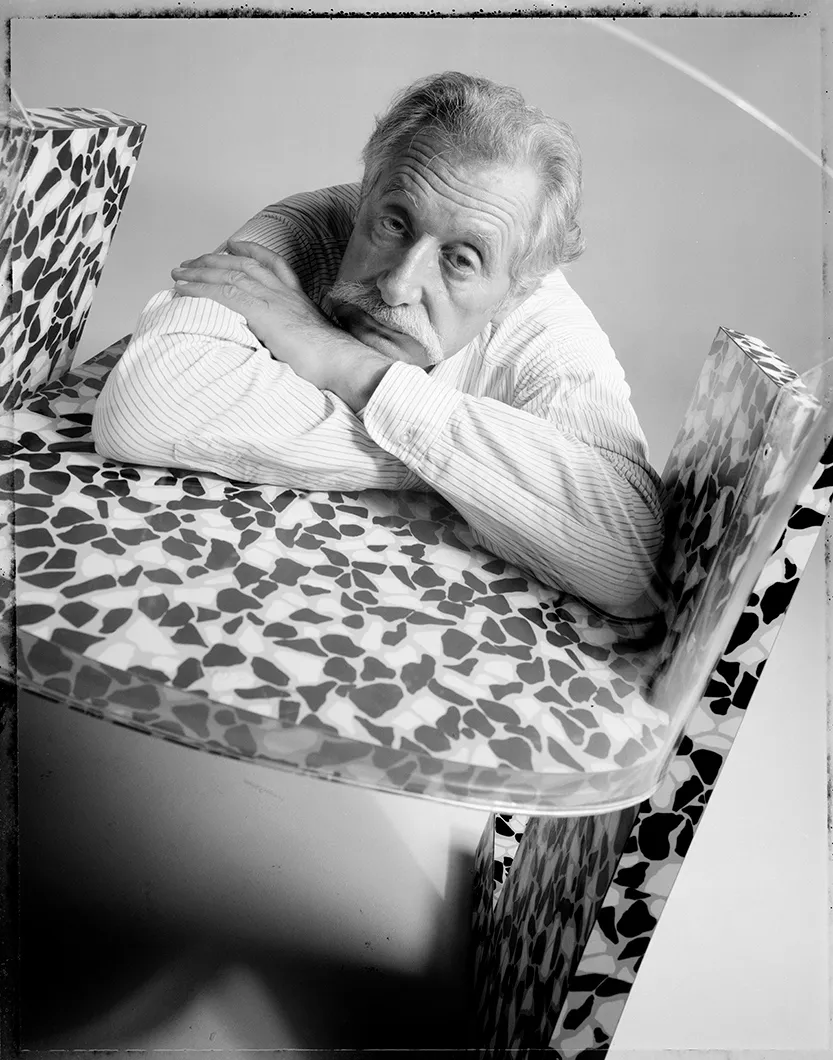

Raffles Milan Fashion and Design Institute took part in the city’s Design Week with a number of exhibitions and a programme of open conferences, in partnership with Leica Akademie Italy and Blue Note. And here, at Blue Note, is presented the “Quintessenze”, exhibition of portraits of the great Milanese designers, captured by the lens of the late photographer and teacher Efrem Raimondi (1958-2021. The exhibition is curated by Denis Curti, Director of the Master’s in Photography at Raffles Milan.

Efrem taught photography at my school, Raffles. We dedicated the studio to him because he really was much loved by the students, he really enjoyed teaching.

There’s a wall dedicated to Efrem at the Still Gallery, with all the photos he took for Interni. We put together an exhibition entitled Photographing Art, a collection of a dozen or so photographers who have contributed to art photography and who therefore worked with the artists. Efrem is also featured, and that happened naturally because I had a really special relationship with him, as it happens. When I was Managing Director of the Contrasto photographic agency, Efrem was one of our photographers. As director it was my job to coordinate the work of our authors and naturally, I worked very happily with all of them, and particularly with Efrem. When he left us so suddenly, we still had loads of things to say to each other.

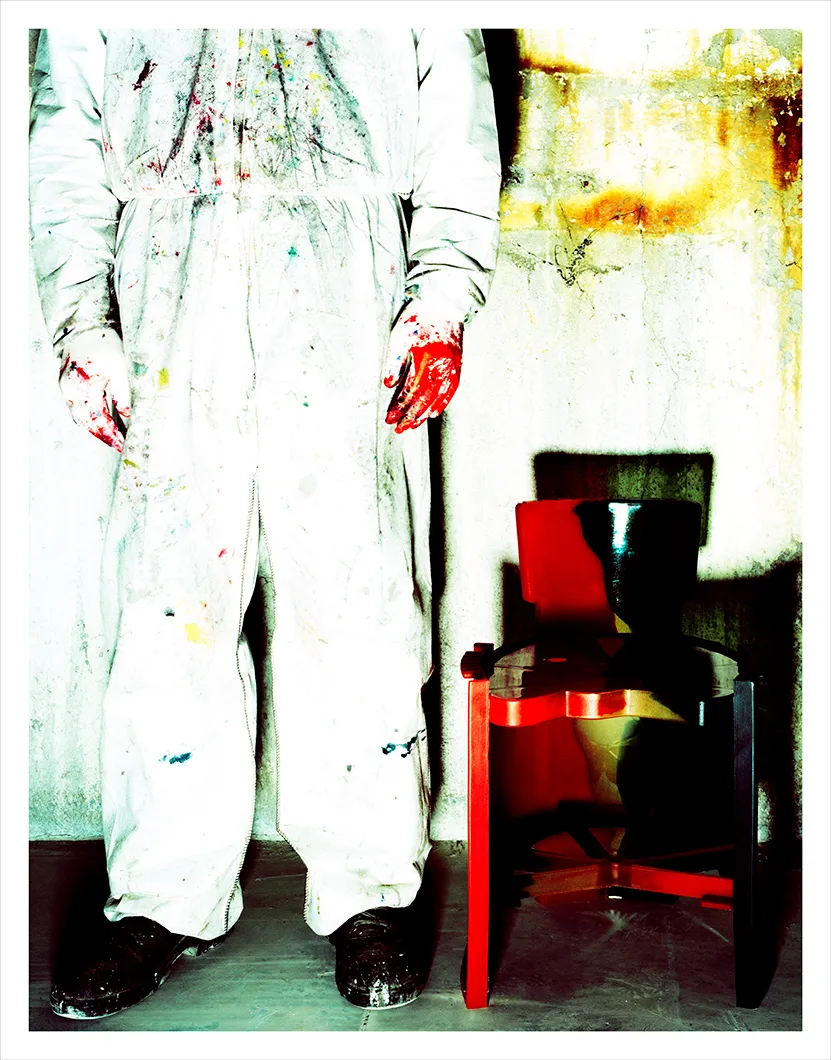

There are two things that always really struck me about Efrem’s work. The first was that he didn’t believe in physiognomics and that’s really quite interesting, because when people see portraits of themselves, they are hardly ever pleased. You have to have a good eye and a strong sense of abstraction, because you obviously know what all your defects are and, paradoxically, a good photographer can make you see these defects even better. It’s not that they make them more obvious, they just make you see them better. He, on the other hand, maintained that physiognomics didn’t exist, which accounts for his approach to portraits. We chose his portraits of the great Milanese designers for this exhibition. Efrem’s thing about the absence of physiognomics was incredible because – as he said and wrote more than once – whether he was photographing Pupo or Renzo Piano it made absolutely no difference to his approach, in the sense that he believed – and so do I to some extent – that when you’re in front of a camera it’s like being at the cemetery: we are all equal. That, if you like, is also the power of the intellectual democratisation process of photography. He was a portraitist even though he also did things for design, because it was a subject that really interested him. Secondly, I can say that he was a militant photographer, so he put the same commitment, the same time, and the same energy into photographing Vasco Rossi (with whom he had a special relationship), or Valentino Rossi or anyone else. I’ve always liked that because when we worked together, as one used to say, “he always took his work home” and you could be sure that he put exactly the same spirit and power of expression into it even when people were less important. This gallery of portraits confirms that in a way. He was the last remaining punk in photography. He was a real punk. He had been one when he was young and he remained one throughout his life, because there was this side to him that photography was something that he did, it wasn’t a “job.” Perhaps this explains why some of the stances he took, certain fits of temper, didn’t do him any good, but they happened precisely because he took an almost physical approach to photography. This set him apart from many other colleagues in the sense that, as I say in the text that accompanies the exhibition, for Efrem Raimondi, photography was always an opportunity to create small and sometimes large revolutions, because he gave a hundred percent of himself every time. He was a firm believer in the democratic profile of images and was always available to others to record those magical moments of introspection that naturally accompanied and dwelt inside so many private stories. Why was he a great photographer and why did he assert that physiognomics didn’t exist? Because his photographs could have been just as at home in family albums. Scianna always says that the highest aspiration for a photograph is not to end up on the front pages of the New York Times, but in a family album, because that means it contains all the ingredients that make up recognisability. I’ve just curated an exhibition in Milan on Lartigue, an author Efrem really loved, at the Diocesan Museu. What struck him was that he put together 200 family albums – which seems a colossal number, if you think about it – at a time when family albums no longer exist, replaced by telephones. The characteristic of Efrem’s images is that they could be used in a newspaper or in a family album, even though they’re never passport photos and have a certain dimension to them.

He had a blog and spent a great deal of time on interface and teaching. I can tell you that he was a rather shamanistic sort of punk, a contemporary shaman who was followed by a great many people because of his ideas around photography. For example, in terms of his readiness, when Toni Thorimbert decided to do a book about Vasco he rang Efrem, because he knew something that was all to evident but that no-one could see – which was that Efrem had taken photos of Vasco that were different. The book is called Tabula Rasa which is a fantastic yet presumptuous concept, but who cares, long live presumption! They produced a wonderful book between them, working together so that the photos in the book are all mixed up and that yet again is the proof, the demonstration, of what photography really was for Efrem.

No, I’ve put four photos by me in the gallery and we’re putting another twenty in the Blue Note, even though there should be 100. He also worked a lot with diptychs, and there’s no reference to that in the exhibition. We’re putting on this exhibition for many different reasons, the first of which is to remember him, and we’re doing that because there’s the Salone del Mobile.Milano. We believe that he was an important observer of this design world, so it’s only right. We’re doing it with Raffles because, as a teacher, he was much loved by his students there; we’re doing it at the Blue Note because we believe we should make an artistic contribution outwith the usual canons. Then we’ll set about putting together a major exhibition. I don’t know where, or what it will be like, so no, the retrospective will come later.

Before coming to Contrasto, he was with Grazia Neri, who was our competitor and had held an exhibition on Vasco Rossi at the gallery in Via Maroncelli. On the opening evening, the road was blocked – I don’t know whether it was because of Vasco or Efrem. The photos, as they say, had been “welded” together. Well, one got stolen and the news ended up in all the papers. Efrem was delighted when they stole that photo. I think a punk like him needs some really special installations. For example – and I say this with a smile – he was one of those people who just wouldn’t stop talking, he chatted on and on and luckily there are lots of recordings and videos of him. I would love to show some images, but what I would love even more would be to hear him telling us his thoughts on photography, how he wasn’t really interested in a photo in a frame. Of course he was interested in the collectors’ market and he sold his photos, but that wasn’t the focus of his work. It’s a good question, we’re giving it some thought and we’ll try and come up with a response.

There’s an entrance corridor which struck us as a natural gallery, and we used it to display images that aren’t hugely valuable but faithful to Efrem’s guiding spirit. For example, he really loved blue-black printing, using found materials almost, especially in these diptychs. He had this physical sense of photography. We put together a gallery of portraits of people with strong ties to the city of Milan. He lived in Busto Arsizio but he was Milanese through and through; it was a city he really loved and where he spent a great deal of time. The exhibition is beautiful, elegant, refined without being, as it were, a jewellery shop. That’s precisely the impression we didn’t want to give, that of a jewellery of photographs.

I think these photographs and the thoughts we had around the democratisation of photos and images, on the concept of family albums, on this seemingly easy photography that actually masks a significant complexity, are an opportunity to think about contemporary work and about the fact that we are all photographers these days. This didn’t bother Efrem at all, he wasn’t bothered about “unfair competition” – if it was unfair: I think there’s room for everyone. He actually shared Giovanni Gastel’s belief that photography was enjoying a second renaissance. This exhibition wants to affirm the fact that Efrem Raimondi was a major part of this renaissance. He wasn’t the sort of photographer who stubbornly defended his position, fighting a rear-guard battle against this “fake professionalism.” No, he threw himself into it and was really happy when he came across a particularly talented photographer. He was pleased, he enjoyed it.

Let’s take a step back: I believe that photography is a scenic art – digital photography aside, which can introduce so many elements that aren’t actually part of the scene but are digital files, so I don’t understand why it should be called “photography.” Take a photographer like David LaChapelle, who’s capable of taking a week to take a photo, because he reconstructs everything. First he makes sure his studio is watertight, then he floods it, then he adds relics from a ship, a bashed-up car, a garage sign, 32 naked extras all at the same time … obviously it takes him a week. Then there are photographers like Efrem who get to know their subjects. I think his real point of reference was Avedon, especially the "Workers" in which there was nothing scenic, nothing but the power of the image. Efrem’s ability and strong point was to make photos out of nothing, despite recognising that photography was a scenic art. He never got his subjects to pose. He told me that when he went to photograph Vasco Rossi for the first time, the first thing Vasco said to him was: “I hate having my photograph taken.” So he put away his camera and they spent some time together. Luckily it was in America, where Vasco isn’t famous and so, given that no-one knew him, he didn’t have to behave like a star. They went to the restaurant, they walked along the road and gradually, spontaneously the right time came along. “You do what you have to do and I’ll talk” – there, that’s the way he did things, a lack of focus on physiognomics. It’s incredible that Vasco then decided to use some of the photos in which you can’t even see his face, you just see his boots, his trousers, but you recognise him through the iconography and you say: “that’s Vasco.”

A play space is a serious matter

Not just fun places, but true places of social focus, where individuals gather, create bonds and build trust

The second edition of the Roundtables on Milan Design (Eco) System

Discussions ranged from the role of cultural policies and training, the appearance of new publics and emerging practices, all the way to innovative networks between territories and design. This is an account of the day’s work on Thursday 25 September, as part of the research project promoted by the Salone del Mobile and the Politecnico di Milano