The furniture and design segment dedicated to life en plein air. Interview with Roberto Pompa of the Assarredo Presidential Council as well as President of Roda

Design stories and much more

Books for the curious readers – from forgotten objects to the quest for perfect beauty, from the Made in Italy to the allure of kitsch, from the power of design to the most glamourous spas, from the hottest homes to snapshots of real places with an unreal feel and activity books.

Massimo Mantellini, Dieci Splendidi Oggetti Morti [Ten Amazing Dead Objects], Einaudi, 2020

“When Herta Müller was being presented with the Nobel Prize for Literature at the Swedish Academy in 2009, she began and ended her speech … talking about her handkerchief. The one her mother never failed to tuck into her pocket when she left the house as a little girl.” A situation many of us can identify with, despite never having won a Nobel prize: a handkerchief as an example of a “forgotten” object that, even then, was not so much something to blow one’s nose on as a mark of a deep-rooted family association.

It’s but a short step from outdated objects to dead ones. Massimo Mantellini lists 10 that are worthy of note: geographical maps, landlines, pens, letters (to friends), cameras, newspapers, records, wires (as in cables), silence, and the sky.

(Every single one of us could put together a list based on our own experience: architects and designers would probably cite parallel lines, rapidograph pens, sketching paper, rolls of tracing paper and razor blades).

Some of the above categories hold particular meaning, like the Michelin road maps, the size of a sheet, perfectly folded on purchase but becoming increasingly limp with every consultation thereafter. Taboo objects for children (and women, as a rule of thumb), a demonstration of virility for the head of the family.

What about letters? What will replace those condensed missives of intimacy and secrets that have built up into an entire epistolary that over the years? An email that nobody will ever print out, no matter how intense? A text? Good for a clandestine erotic encounter, perhaps. No nail-biting wait for a reply that we hold close to our face in a bid to catch the tiniest waft of perfume before setting to with the letter opener.

Lastly, Mantellini cites silence and the sky, which I personally would put into the same category. They are certainly lost (the former as regards perpetual connection and the latter as regards light pollution), but hopefully not dead forever, in fact I believe that they will fuel our protest march – it is up to us to come to a decision about them.

Carlo and Renzo Piano, Atlantis: a Journey in Search of Beauty, Feltrinelli, 2019

Beauty, hunted like a “White Whale” certainly lies within the pages of this intimate diary. I believe, though, that aside from storms and undertows, this is primarily about a father and a son and the increasingly rare opportunity (as those of us with children know only too well) to take stock of their relationship. The father, now in his eighties, is a famous architect, and his son awaits and filters his words as if processing a viaticum for life in the future. The most fascinating part of this particular log book is that the NEED for a relationship is hidden under the exceptional events it records.

After leaving Genoa on an ocean liner, Piano father and son travel around the world and, as luck would have it, along the way they end up in places such as Osaka, Athens, London or New Caledonia, where Renzo has endeavoured to build a message of beauty.

The journey has its own set timescales and rhythms (punctuated by characters such as the boatswain and crew) – no chance of stopping a bit longer in New York (to have another look at the Morgan Library, Columbia University, the New York Times skyscraper or even the new Whitney), or in London (to ponder in the pointed shadow of the Shard).

The search (for Atlantis, i.e. for perfect and therefore impossible beauty) has to go on: “You’re searching for Atlantis, you don’t find it, but you still go on looking for it. There’s always something missing in what you do, and it’s that that twists your gut.” The sort of gut wrench (that we poor mortals are all too familiar with) that makes the great Renzo endearing and, I would say fraternal. It’s precisely this gut wrench that the son records, building after building, location after location, in the overwhelming realisation that the architect is not a painter, as Gio Ponti always said, and is not therefore in a position to erase any of his work.

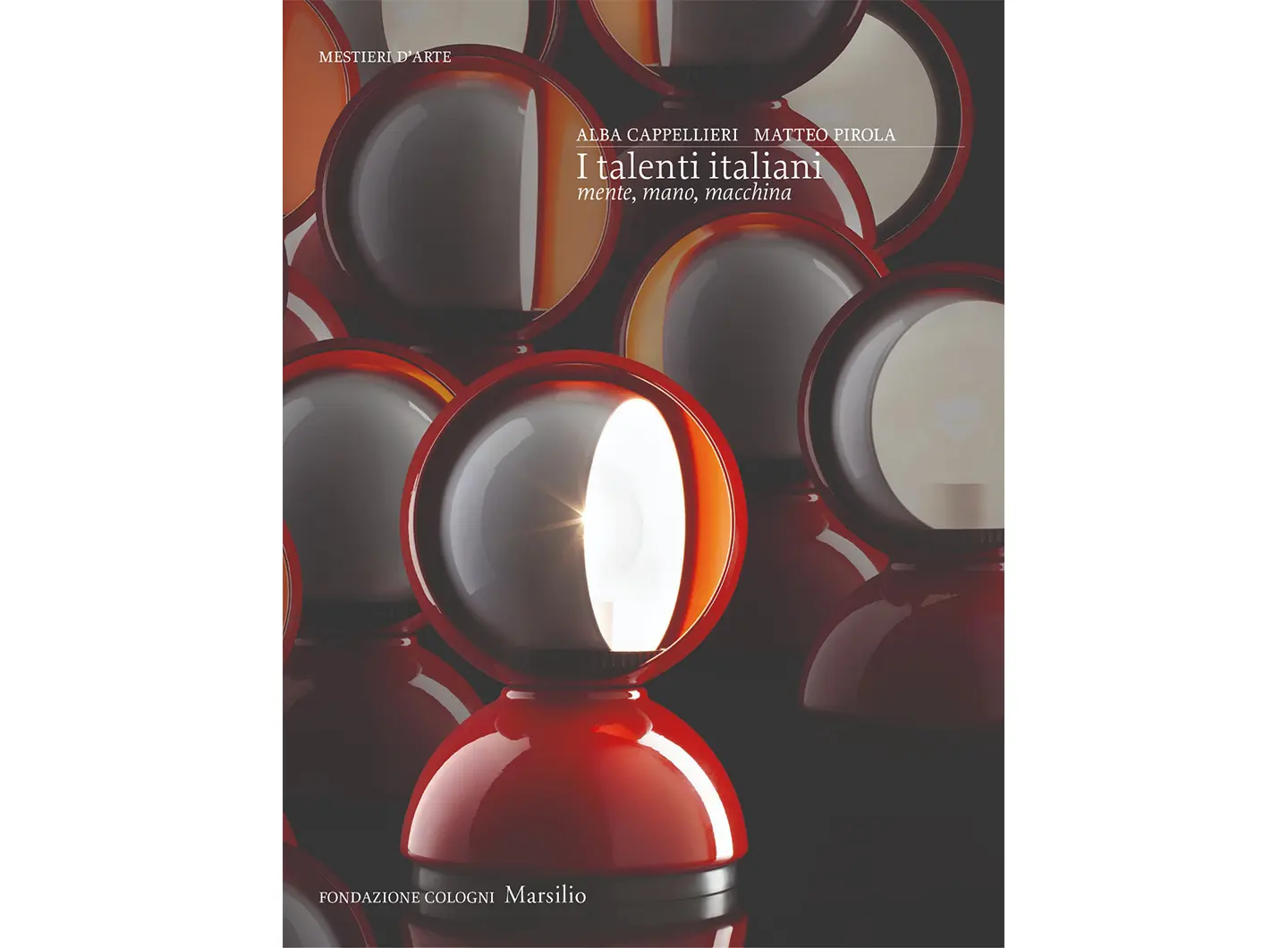

Alba Cappellieri, Matteo Pirola, I Talenti Italiani: Mente, Mano Macchina, Fondazione Cologni – Marsilio, 2020

The quest for the secret of Italian design is (and has been) somewhat akin to the quest for the Holy Grail. Foreign countries, holders of extraordinary technologies, start-up inventors, economists and financial analysts have all been dying to possess it. Yet, that secret, which was really right in front of everyone’s eyes, was kept well hidden. What was it that enabled the Italian furnishing industry to become the foremost in the world? Being open and welcome to creativities from faraway “other places”? Alba Cappellieri and Matteo Pirola tell us about it, but without betraying anyone. They lift an extremely delicate lid, set out certain evidence: the Italian furnishing industry has never been an industry tout court, rather a subtle mix of craftsmanship and industry, of hand and machine (as the subtitle of the book suggests). Manual processes such as sewing leather, galvanic coating and perilous assemblies have always not just gone hand-in-hand with serial production but overlaid it, on the same object. Basically, in most cases, the “industrial” production of Italian design has always been “finished” by a non-industrial process. An “artisanal” dimension, the legacy of savoir-faire from the workshops that from time immemorial have characterised Italy. The first to discover this were not the entrepreneurs (who, at one time, really did play at being “industrialists”) but the designers, their unstoppable imaginations demanding parts in blown glass (from Murano) for huge table or floor lamps), or a wrought iron foot, from a real blacksmith in the old part of Milan. Thousands upon thousands of masterpieces have been produced in this way.

At the time, nobody bothered to wonder whether these were industrial or craftsman-made products or even a mix of the two, what counted was that they were good looking, extraordinarily good looking, and that they sold in their thousands, right across the world, thanks to their je ne sais quoi, their unquestionable diversity.

Just recently, and just because of the crisis, we have found ourselves in a definitory loop, distinguishing the hand from the machine, creating taxonomies that are as curious as they are pointless (60% artisan – 40% industrial? or perhaps 65% artisan and 35% industrial), with press releases extolling the total craftsmanship of a largely machine-made object. But as we know, words have become devoid of meaning since everybody started using them. Now Cappellieri and Pirola have come along to put straight first the history of Italian design and then the currently applicable defining product categories in a book that is rich in strong iconographic heritage and, especially, an approach that includes young designers and more marginal research.

Kitsch, edited by Marco Belpoliti and Gianfranco Marrone, Riga 41, Quodlibet, 2020

We’ll get round to kitsch later, of course, but in the meantime I would like to focus on the structure of this imposing piece of research. Belpoliti and Marrone have brought together thirty three fundamental essays on kitsch, from the early 20th century to the present day. The roll call includes Walter Benjamin, Theodor W. Adorno, Marshall McLuhan, Susan Sontag, Umberto Eco, Gillo Dorfles, Jean Baudrillard, Arnold Hauser, Alessandro Mendini, Ettore Sottsass, Milan Kundera, Italo Calvino and Vilém Flusser. Each essay, moreover, is duly but briefly commented on by a contemporary critic or philosopher, creating a what amounts to a platform for virtual discussion. They are closely followed by a questionnaire completed by 27 intellectuals, designed to tease out the definition of kitsch, its status as a uniquely aesthetic or even political phenomenon, and the differences between gadgets.

This all adds up to a total of 605 pages that can be read all in one fell swoop, making it easy to compare the different theories. Does it all make for the same response? NO! Whatever kitsch was, whatever its origin (a meta-historical phenomenon or invented by the upwardly mobile petit bourgeoisie during the romantic period?), how might it possibly be defined today? While on one hand, it would appear that it permeates contemporary culture, in the form of generalised bad taste, on the other, the actual meaning of kitsch, and therefore of “taste”, good or bad, is up for discussion. The Western culture’s loss of centrality and the consequent prevalence of hybridisation and multicultural concepts make it hard to take up a definite position in relation to kitsch, leaving it up to the views and sensitivities of each one of us to respond on our behalf. What is however certain, going back to the initial premise, is that this is how the historical and critical problems must be tackled, deploying a solid research methodology that will do away with so many meaningless words that we hear and read on a daily basis. If a criticism is absolutely necessary, the only regret is that the editors have failed to provide their final summary, venturing their own definitions of kitsch.

Satyendra Pakhalé Culture of Creation, AA.VV., nai010 Publishers, 2019

Talking about hope and optimism right now is quite a challenge, with the pandemic in full swing. This is the message that comes out of this monograph, the first, on one of the leading names on the international creative scene. It explores the role of design in promoting common good and its unifying power in an ever more divided world. As Satyendra Pakhalé puts it: “Design is a cultural act about justice as much as utility and beauty.”

Aside from the free thoughts of the Indian polymath designer, launched by SaloneSatellite in 2001, Culture of Creation contains critical essays by leading design and industry thinkers such as Paola Antonelli, Tiziana Proietti, René Spitz, Aric Chen, Juhani Pallasmaa, Stefano Marzano, Jacques Barsac, Wera Selenova and Ingeborg de Roode – throwing a new light on the role of design – which is to nourish the common good, crucial for social cohesion. There also emerges a designer who is farsighted, attaching a soul to his work, a kind of modern-day Geppetto, who doesn’t allow himself to be drawn in by the facile consumerism of industrialisation. “I have always seen the world as one place, I don’t know the world as a divided place. We as a humanity are innately related – and unfortunately, the current politics don’t reflect on that. […] The ways and manner in which we are fed with selective targeted information by any given search engine, at any time of day, limits the way we approach things, and our possibilities.” For Pakhalé, being a designer is a true expression of optimism. A sine qua non condition for being able to create. The culture of creation, precisely. Every creative process presents its own adversities and difficulties that are hard to overcome without adopting this specific approach.

The book also contains some fine watercolours. Pakhalé has loved sketching and drawing in pencil since he was a child. When he set up his studio, he began the daily practice of painting watercolours on cotton paper, using a single brushstroke. These constraints allowed him to focus only on the practice and “think through abstraction,” in other words, discarding the rational part in favour of intuition and subconscious vision.

What we should take away from this wonderful book is this valuable lesson: “Design has to help to bring the disintegrating elements together and unite them in a given society.” Now more than ever!