They are all Italian and all in some way draw on the theme of memory. This is true even when they deal with current sporting events associated with the imminent inauguration of the Winter Olympics. There are ten of them and for the most part they are held in the most reserved cultural circuits, outside the mainstream. It’s even better when they’re out of town, bringing historic residences to life with gleams and flashes of good design

The Formafantasma projects for the Salone del Mobile.Milano 2024

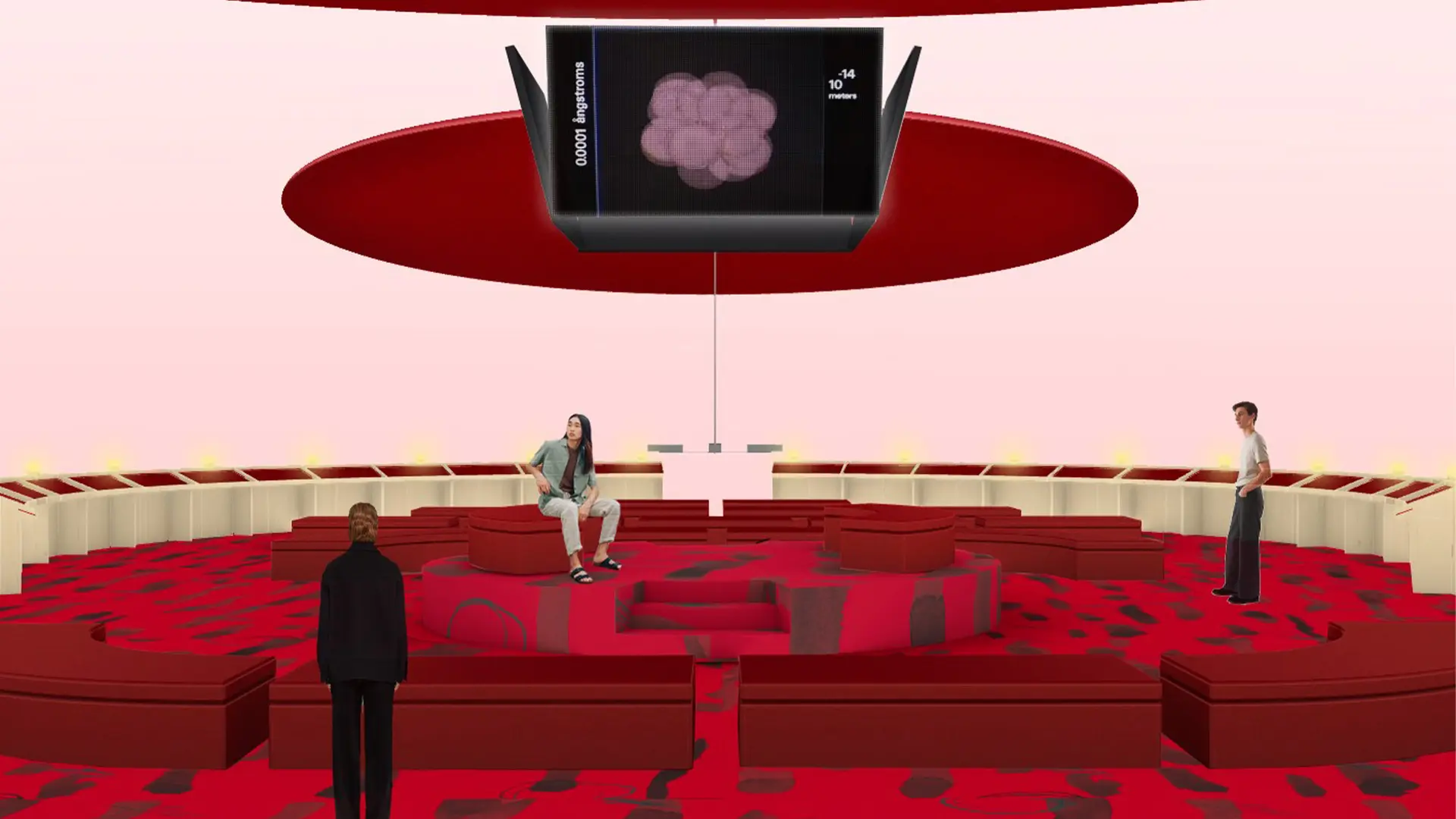

Arena "Drafting Futures" - Courtesy Formafantasma

A conversation with the designers Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin, designers of the Drafting Futures Arena for the 2024 edition of the Salone del Mobile.Milano, where the Talks will be held, and also of the Salone del Mobile Library and the Corraini Mobile Bookshop

Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin, known as Formafantasma, underscore the fact that theirs is a commercial, rather than an academic practice. Since they set up their studio in 2009, they have been creating vases, lamps and other exquisite objects; and yet their sphere of work goes well beyond product design. "Being a designer calls for both an analytical and a meta-analytical approach,” they say. “It’s not just a matter of thinking about a product, but also of reflecting on what being a designer in the contemporary world means. The act of creating something new should always raise existential questions.” While their products may not be accessible to all, their work attempts to raise everyone’s consciousness. They are the authors of elaborate explorations intended to unmask the non-virtuous practices in which the design industry is complicit, in an attempt to reconfigure the system. Over the years, Trimarchi and Farresin have also shown themselves to be excellent designers of spaces, or rather of spaces that become systems for thinking. They are back at the Salone del Mobile.Milano this year, with their designs for the Drafting Futures Arena, which hosts the programme of Talks and Round Tables curated by Annalisa Rosso: Drafting Futures I Conversations about Next Perspectives, as well as for the Salone Library and the Corraini Mobile Bookshop.

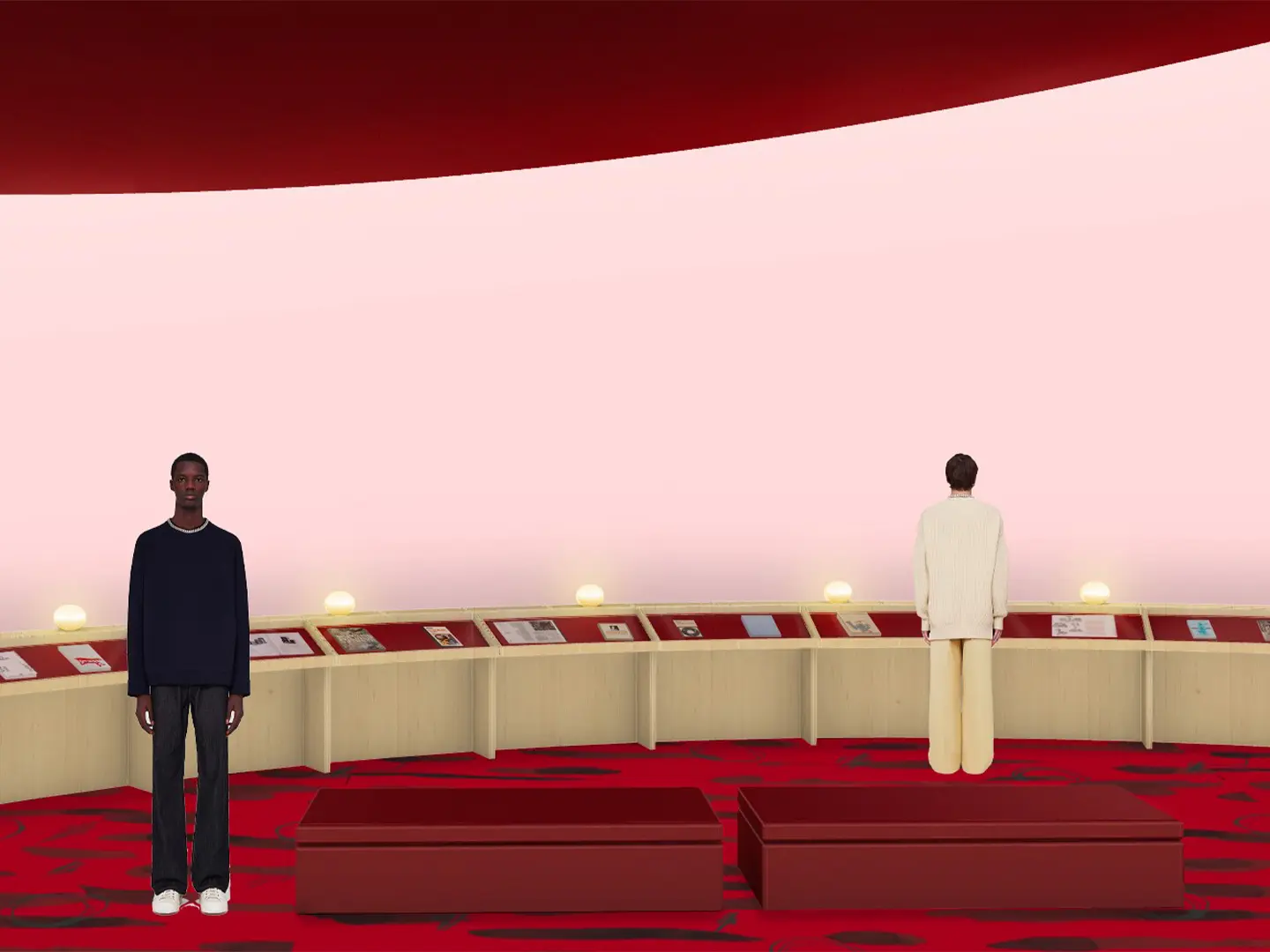

Our decision to work with a view to reuse was fundamental, upcycling the seats from the previous edition. These were recovered with carpet printed with abstract designs, similar to the doodles we make when we are thinking hard or talking on the phone, like the exterior signs of a complicated thought process. Moreover, the Talks this year will no longer adopt a ‘frontal’ approach, as we have configured the space in such a way that the speakers will be in the centre and the spectators will be able to take an active part in the conversation, rather than simply remaining passive. The project also includes the adjacent Corraini Bookshop, while the same seats will be positioned right along the entire route of the event, providing opportunities for visitors to take time out.

The intention is to put together an “ideal library of contemporary life” by asking the hosts of the Talks [including Francis Kéré, John Pawson, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Maria Porro, Ed.] to each suggest a book. Then we will set up an exhibition of books along the perimeter of the Arena, which will breathe life into the space when the conversations aren’t ongoing. The idea is for the project to carry on, year after year, gradually creating the Salone del Mobile Library.

We don’t really care for the word per se. It was originally used in Germany to indicate forest management. The idea was to spark a virtuous circle to ensure that the tree cutting cycles were proportional to the renewal of the plant life. So it was geared to economic sustainability; but that means having a business model. We prefer the word ‘ecology’ because it goes further than the environmental connotation, implying the interconnectedness of everything.

Yes, although that doesn’t mean that everything we do is "ecologically sustainable".

It’s not just that. We have split our practice into research projects and projects for companies; the aim is to ensure that our projects are geared to companies while our research topics are, often, influenced by experiences acquired in a commercial field. This fragmentation allows us to find an ethical balance that works well for us.

It is a model based on the assumption that resources are infinite and that growth is the only option. Obviously, we can make as many ‘sustainable’ products as we want, but it is the capitalist system as a culture that is the real problem. The climate crisis requires us to build a different way of thinking, and we believe that this is a very interesting intellectual challenge.

Bookshop Corraini Mobile Courtesy - Formafantasma

We wanted to engage with an archaeologist [Marco Giglio, Ed.] to explore recycling strategies in a historical context. There aren’t actually any clear signs that Pompei had a landfill. However, after an earthquake, much of the reconstruction seems to have been carried out using the debris from collapsed buildings. We also discovered that the water conduction systems – underground or gutters – were fashioned from broken terracotta jugs. So pottery was reused in architecture. The most interesting thing that came out of it was the continuous migration of materials towards new functions. It seems to have simplified, or rather reduced, the variety of materials employed, leading to greater flexibility in their use.

We questioned the concept of domestication by examining the relationship between humans and other mammals. In nature, when you observe two animals living in close proximity, and benefit from the reciprocal association, it’s called symbiosis. But if you take sheep, for instance, or dogs, we talk about domestication. However, when exactly did Man domesticate sheep? Their progenitor, the mouflon, shed its hair spontaneously, and it is unclear exactly when it became domesticated and referred to as a sheep. We believe the idea of domestication to be anthropocentric, based on the belief that it is Man who shapes the world and the other living beings around him.

If we hadn’t had the possibility of covering ourselves with woollen garments, we would never have ventured into certain geographical areas. In the practice of nomadic pastoralism, it is difficult to say who follows whom: do you move based on the needs of the sheep or of the people? They are complicated relationships; sometimes relationships of love and solidarity, other times of abuse and pain.

That is certainly the case. If there is a preference, it probably means that there is a bias, and we are very suspicious of the things we like. It has to be said, we have great respect for intuitiveness; However, the next step is to understand why we like a certain thing.

Often. There are designers who work on the basis of what they love and designers who work in an attempt to change what they don't like. Right now, we belong in the second category.

When we were studying at the ISIA in Florence.

Very. Work becomes conversation-based: words are more important than images at the outset and, in a sense, the feeling is that the design outcome has a more objective component.

Organisation, talent understood as sensitivity to the medium and the context with which one works, a range of different skills and analytical ability.

Yes and no. Sometimes we ask ourselves whether we love our profession, because much of our intellectual or research work is an ongoing critique of design. However, this primarily means questioning the status quo of the world in which we live.

This has been the case with many great designers. Take Enzo Mari, who demonstrated that design is a political gesture, or Alessandro Mendini, who brought philosophy into design.

Adolf Loos, Nikola Tesla, Nina Simone and Alexander von Humboldt.

Milan.

That’s not a dichotomy we believe in.

Clément.

How can you separate the dog from the sheep ... the dog was the guardian of the flocks ... But in the end, I would say dog, inevitably...

Meanwhile, their little Italian greyhound Terra looks on from the sofa.

Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin - Ph. Renee de Groot

Exhibitions

Exhibitions