The furniture and design segment dedicated to life en plein air. Interview with Roberto Pompa of the Assarredo Presidential Council as well as President of Roda

Francesco Binfaré

Photo Credits Isabella De Maddalena

This extremely vivacious Milanese is the undisputed king of sofas and a contemporary Ulysses, travelling through the history of design.

Essentially, an artist and designer. In actual fact, so much more. Starting with his role as director of the Cassina research centre, from 1969 to 1976, which enabled him to practice art in an industrial environment. He also went on coordinating the production of Mario Bellini’s Karasutra minivan and Gaetano Pesce’s subterranean habitat for one of the great milestone exhibitions in the history of Italian design, New Domestic Landscape at MoMA in New York in 1972. In 1980 he set up his own Design and Communication Centre for researching and promoting design projects, some of which were developed for Cassina, including Mario Bellini’s Cab, Toshiyuki Kita’s Wink, and Gaetano Pesce’s Tramonto a New York.

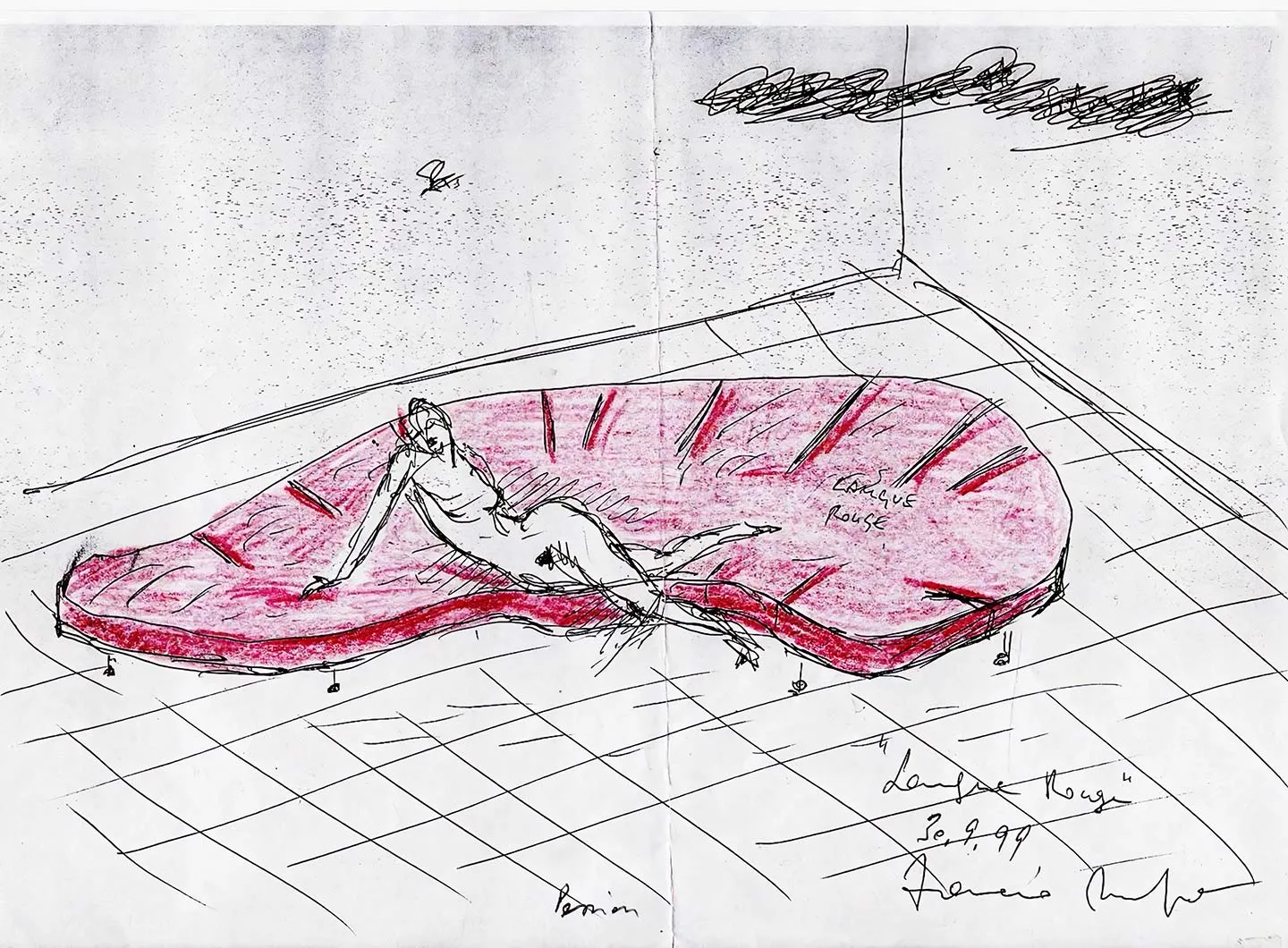

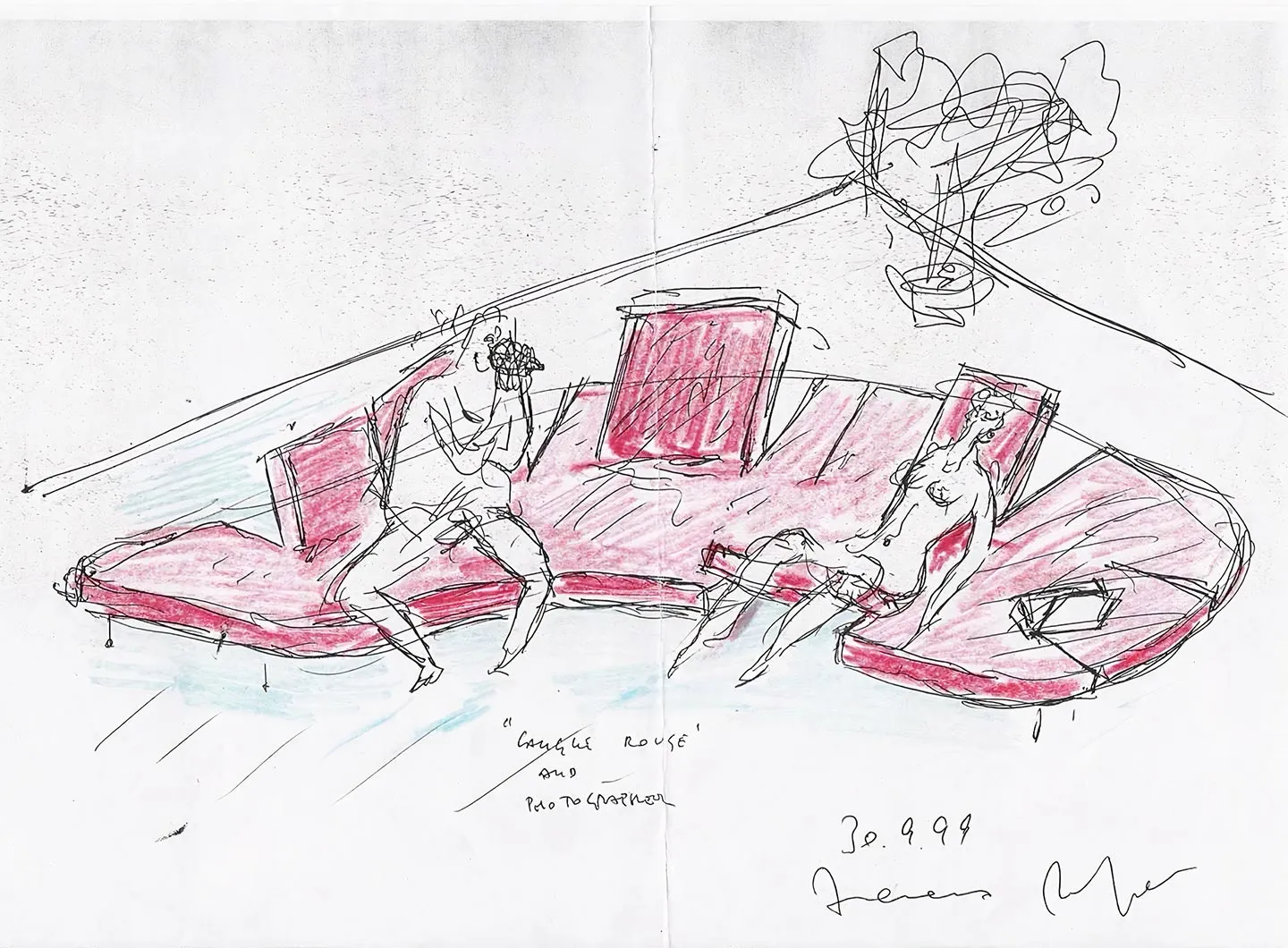

An extremely lively non-conformist, Binfaré was born in Milan in 1939 and is the undisputed king of sofas, having designed an infinite number of them over his sixty-year career. Timeless, apparently simple, large-scale sofas, dispensers of wellbeing that combine technology and natural materials. Crosses between sofas and sculptures, such as L’Homme et La Femme, which was also the first ever to introduce variable configurations; or deconstructed and versatile like Flat; soft and welcoming, like Standard; or inspired by the Orient, flexible; adaptable, classical even, right up to the famous Pack, a bear on lying on its side (the backrest), on an ice pack (the seat). Provocative, and a catalyst for reflection for us all.

His father taught him how to paint and draw, skills that he then drew upon in his pursuit of design, exploring original methods for triggering creativity and involving architects and designers in the creation of products that have become Made in Italy icons, from Vico Magistretti’s Maralunga to Mario Bellini’s Bambole, Paolo Deganello’s AEO chair and Gaetano Pesce’s Up and Sit Down.

He took part in the travelling exhibition on the future of the technology at the Triennale in 1982, the same year as he embarked on his successful and prolific collaboration with Edra. A visionary, he has designed installations for new product launches, inventing what we now refer to as the concept of an event, and promoted experimental initiatives showcasing cutting edge objects, such as Bracciodiferro in 1973, with Gaetano Pesce and Alessandro Mendini, and Environmedia in 1974 with Mario Bellini and Pierpaolo Saporito, promoting the use of interactive media in design practice. A contemporary Ulysses, navigating the history of Italian design.

I was born into art and am still working in that field and exploring the graphic rather than the technical side of it.

It’s been ages since the inspiration or idea for a design piece has been sparked by technology. A new technology can serve as a trigger because it presents an opportunity not to be missed. The seed of an idea is always planted by an urgent need to express a poetic vision that has matured through slow observation of how habits and behaviours are changing and from a need to represent the time I’m living in.

What a request for work in the field in which I’m regarded as an expert gives me is the extraordinary and fortunate opportunity to create something tangible and useful that shows and gives the world something that did not previously exist and that is perhaps a poetic reflection of many feelings and characteristics of contemporary life.

For example, Pack stems from an exhibition I held at the Biffi gallery, entitled Selfies, showing the disturbing ongoing virtualisation of human encounters. The exhibition was made up of very rapid sketches, rather like smartphone snaps, of visualisations of people on rafts watching the world through their magic tablets oblivious to where the ocean current is taking them.

The poster for the exhibition comes from a quick sketch of a couple kissing while looking into each other’s eyes through their respective devices.

Now, you may well ask why sofas mean such a lot to me. I’m interested in space, light and the human body. I see sofas as the mould for man’s most noble movements. When I design a sofa for mass production, I envision it as a travelling installation. As we are seeing so dramatically now, in 2016 the theme of affectivity emerged powerfully from the ongoing difficulties of expression between people. Equally, after a series of sofas that had to cater for certain movements and represent the positions that were becoming ever freer from 19th century rigidity, I wanted to make a sofa that allowed for complete freedom, shaped so that it would be easy to find the perfect position. I also wanted to convey an image of a global world that was paradoxically fragmenting. Then it came to me in a flash looking at pictures of ice packs: a white bear sunning itself happily while floating on a block of ice, possibly not aware of the danger but living the moment with huge intensity. I chose the ideal position of the bear because it was playful, and I designed the shape so that it could immediately be recognised as a sofa.

I discussed it with Edra.

It was like making a snow sculpture the way they do in Val di Fassa at Christmas, and Pack was the upshot. The environment is an issue that really fascinates me. Even now, and certainly for some time to come, houses will need to be protected from external pollution and research will be a bit like space exploration because the capsules and the satellite platforms also need to be protected from the space and the asteroids and who knows what else. We’re living through an extremely complex time with huge, rapid changes as well as dangers.

The quality of the space, of the light and of the relationship with the body will become increasingly important and valuable. Sofas will increasingly become spaces in their own right and the focus of our emotional lives and of sacrality, a space that can conserve and regenerate the culture of the body and the memory of humankind.

Here’s another example of how ideas can start to burgeon. In early August 2019, I started a story made up of isolated human beings, which seems like a clairvoyant metaphor for what is still going on. The story takes the protagonist out of a serious situation and towards the sea. Taking a primitive boat he comes across on the shore of the island he’s escaping from, he eventually lands on the coast that he set off from a long time ago. He finds a sort of underground construction and discovers a large artificial window inside, which gives onto an unknown, virtual world. The drawings in the story stop there. From there I started sketching out a potential residential solution that could cater for a hypothetical contaminated situation.

I also worked on an installation, as if it were a scene in which the same small group of humans from the beginning of the story found themselves safe inside a room that was transparent towards the outside and reflective towards the inside.

The people in the room are crouched or sitting in a reciprocally protective manner, but so that they can easily communicate. There’s also a large opening bringing in light and fresh air with a beautiful view of the totally virtual outside, i.e. totally removed from the real outdoors. This is a scene that I conceived and worked on from August 2019 to the end of the year, when there wasn’t the slightest hint of the virus that was about to hit. Then, as you know, I had other problems and frankly I thought no more about it. Now I’ve started thinking seriously about it again and I’m keen to get to grips with the story again.

1992.I’d just resigned from my job with Cassina and was putting the finishing touches to the huge Tracce Emozionali Domestiche paintings on double sheets for a one-man exhibition curated byPierre Restany.

I happened upon Massimo Morozzi in the street. He wanted to know what I was up to. I answered: “I’m painting.” So he said: “I’m now the artistic director at Edra and I’d like you to design us something to celebrate 25 years of radical design.”I also liked the fact that our traditional roles of designer and art director werebeing reversed. That led to L’Homme et la Femme, and that led to all the rest.

Yes, all that exactly and other things from time to time. Also a blank sheet for describing a space in time for retelling.

I have to admit that I live sofas as multiples and as travelling installations that can have an energising and vital dramatic effect on homes.

It’s very different. The organisational procedures have changed. New expressive techniques have emerged. I would recommend physical interface to young people, drawing directly onto paper and three-dimensional work done by hand.

People have asked me how I would describe my job. Initially, my response was that the professional category on my VAT statement is: Artist and Inventor. Thinking about it now, I think that I’ve gone on studying right from the start and building up experience to createFrancesco Binfaré, and I haven’t finished yet.