Pure volumes, minimal or non-existent decoration, primacy of functionality, harnessing new materials: from the Casa del Fascio in Como to the railway station in Florence, the story of an experimental period that, after almost a century and several attempts at damnatio memoriae, remains a tangible presence in Italy.

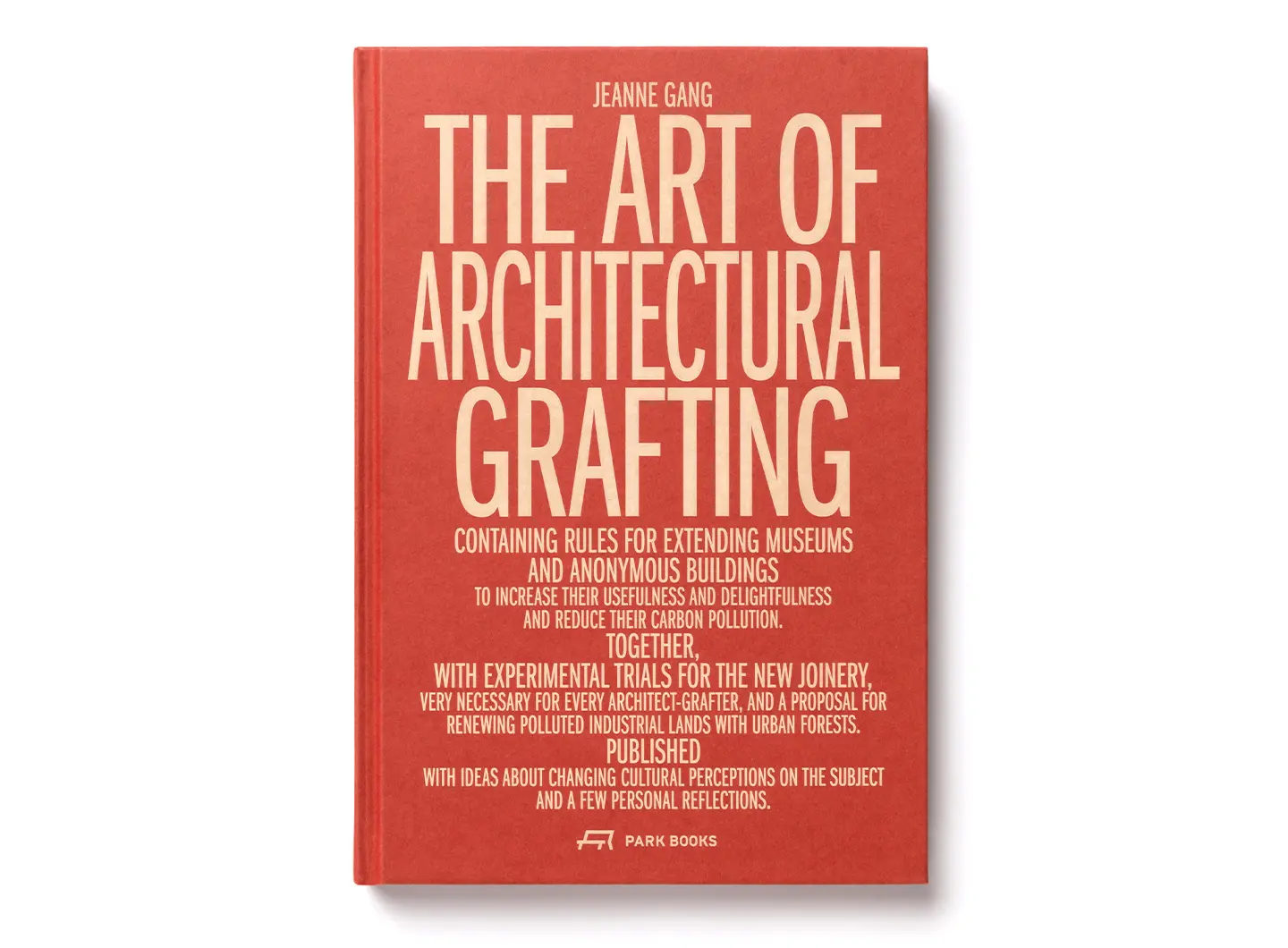

Jeanne Gang, the architecture of grafting

Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts - Ph. Iwan Baan

Meet the new face of sustainable and inclusive architecture, capable of proving that high urban density can coexist with the human scale. And that a botanical metaphor can help us imagine more resilient cities

She has designed a vast range of projects, from Aqua in Chicago – which reductively went down in history as the tallest skyscraper ever designed by a woman – to low-impact wooden structures such as the pavilion of the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival, immersed in the forest that surrounds New York. Yet her most emblematic works are perhaps those where she expanded existing buildings. Jeanne Gang, American architect and founding partner of Studio Gang, is convinced that 21st-century, low-carbon architecture must be conceived as the careful interposition of new stratifications. Or rather like a graft, echoing the title of her latest The Art of Architectural Grafting, just published by Park Books. The book, poised to become a new milestone in the architectural debate, sees in this ancestral botanical art an opportunity to regenerate both cities and their relationship with nature. We talked about her vision and her practice during this interview.

Jeanne Gang - Ph. Marc Olivier Le Blanc

Architects and designers need to reduce the embodied carbon of buildings. We all know this is urgent, and one crucial way we can accomplish it is through renovating and reusing the buildings we already have, which saves 50-75% of carbon emissions compared to building new. This practice has traditionally been the realm of historic preservation. But it has to become far more widespread and wide-ranging, including, I argue, through more radical design interventions that expand the capacity and functionality of the original structure. This is the next crucial step that needs to be taken. Architectural grafting is one approach to making this kind of strategic addition–it’s a concept that I’ve been researching, teaching, and putting into practice for a number of years. The new book is my way of sharing it with a larger community.

Our philosophy of actionable idealism is rooted in the idea that we need to take achievable steps, whatever size those steps may be, to progress toward a healthy society and planet. With every project, we pinpoint the aspects that are ripe for innovation and implementation. Instead of following the status quo, we look to make change where we can through step-by-step actions—getting it done. The accumulation of all these large, medium, and small-scale changes will eventually make big differences, and we want to be part of that. While some projects might have a tightly prescribed design brief, you must still try to recognize how that brief fits within a broader context and how it can establish important connections with wider systems. This is why our Studio gets excited about smaller design interventions, because they can still help tip the balance to larger-scale change on issues of materiality, climate change, or social innovation.

I think of architecture as a frame-like structure that can shape and facilitate people’s behavior and the way they interact with one another. For example, if you want to improve communication between people in a building, you can improve their sightlines to each other or think about how to choreograph the space so that it brings people physically closer together. For example, at the Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation at the American Museum of Natural History, we designed the architecture to spark curiosity and inspire a sense of wonder.The building encourages people to follow their own desire and explore as they flow through it, and engage with the exhibits to learn about science.

My research on horticultural grafting gave me new ideas and language to apply to architecture. Grafting is the agricultural technique of joining two individual plants, one old and one new, so they can grow and function as one. They benefit from each other. Architectural grafting can share these goals. It’s about creating greater capacity from what we already have. Keep the original building but add something new, in a way that will let the building flourish for years to come. Of course, in horticulture there are also some essential rules to follow—you can’t just graft any plant onto another, they must be compatible in certain ways. Similarly, the book sets out ideas about what helps an architectural addition become a successful graft, such as maintaining a sense of reciprocity between old and new.

At the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts, which opened less than a year ago, the building had already undergone several additions that limited, rather than expanded, its functionality. There were lots of unused and uncomfortable spaces. To increase its carrying capacity on both structural and functional levels, we reorganized the existing building’s interior to simplify the flow for visitors and added space for new programs, such as an event space and a restaurant. People have a richer experience when they can more easily move through a building and have spaces for gathering, resting, dining, and other activities.

I think it is possible, but every city is different. More cities need to recognize the importance of investing in the transformation of underutilized public assets into something that can benefit all residents. We saw this in Memphis, Tennessee, with our work on Tom Lee Park, a project that turned an underused piece of infrastructure into a new public park and improved connections between the city and the Mississippi River. Working with different groups of residents during the design process, we learned about their needs, desires, and what they wanted to have as public space. Urban renewal projects are most successful when they have an inclusive design process that values the voices of citizens.

These events not only highlight fertile ideas, but also help them spread to different places around the world. Many of these ideas are conceived as smaller interventions, but they can have a larger effect when you bring them together in one place. But to create real change, these ideas need to reach people outside of architecture, such as governments. We should invite government officials, not only architects, to these exhibits. The farther these ideas travel, the more people they will reach, and the more potential they will have to effect change.

Over time, the way that we work has become increasingly specialized. You often see architects leading the design of the building form, with another team leading the development, another for the structure, and so on. Little by little, architects have given away nearly all the different parts of the building and are losing the ability to understand the bigger picture. To preserve the potential of architecture to make change, we must work to keep its scope from becoming too narrow and becoming just decoration. To remedy this, we can try to be enlightened collaborators, where all design participants engage with others’ roles to provide quality for everyone. We can also directly engage with the project’s end users to better understand what is truly needed and desired.

On Friday 19 April at 11 a.m., Jeanne Gang will be in conversation with Johanna Agerman Ross in the “Drafting Futures” Arena, Pavilion 14.