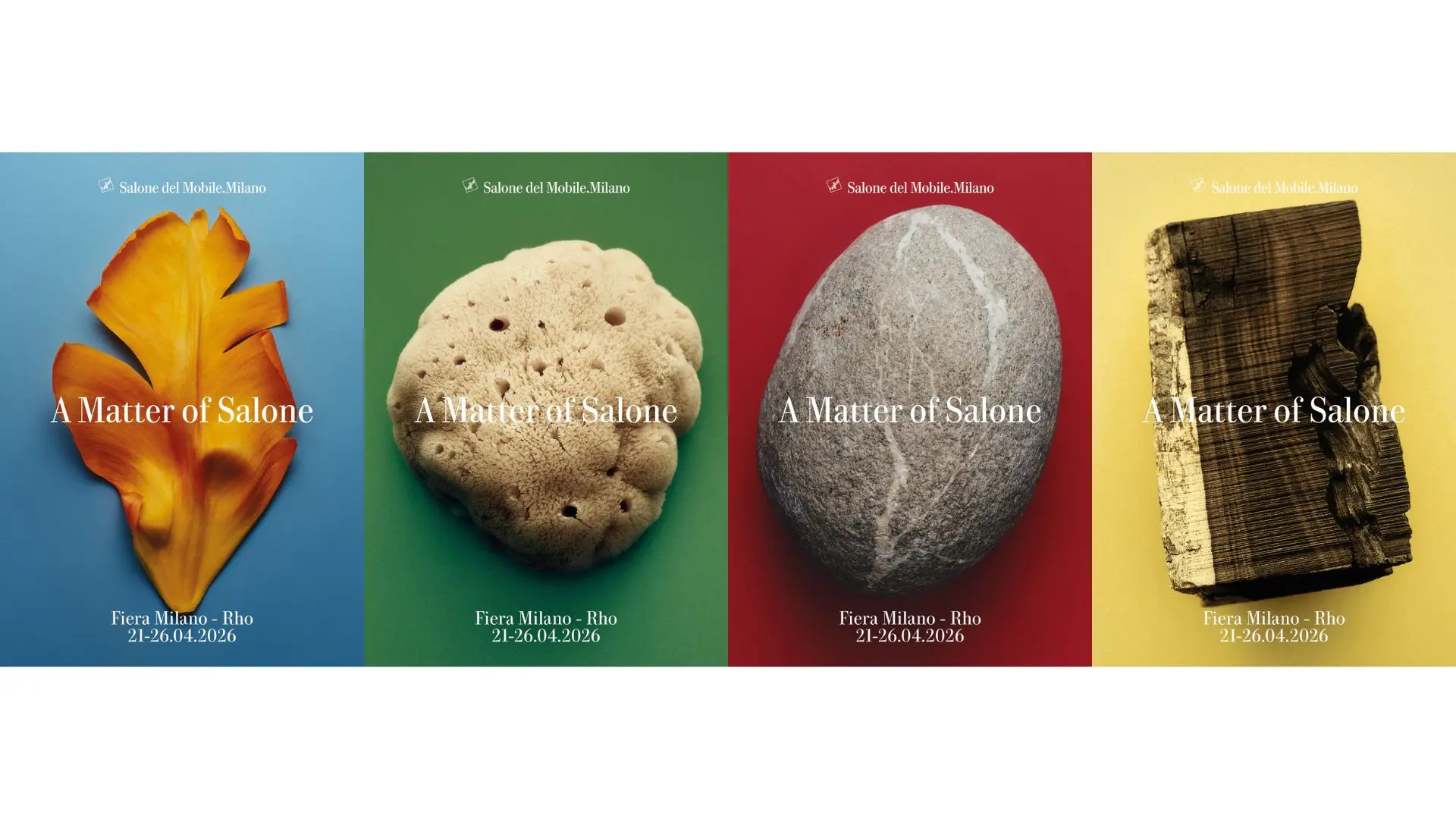

From a reflection on humans to matter as meaning: the new Salone communication campaign explores the physical and symbolic origins of design, a visual narration made up of different perspectives, united by a common idea of transformation and genesis

Zero Carbon Cultural Centre, Makli, Pakistan

With Pakistani architect and activist Yasmeen Lari continues the column that gives voice to the most important and prestigious international architecture firms

Today among my major concerns are both the health of the people and the planet, as for me these are deeply interconnected. For a couple of decades now I have felt compelled to utilize my architectural training in order to foster social and ecological justice especially when designing for large scale rehabilitation of climate migrants. By utilizing my humanistic humanitarianism model as opposed to the prevalent international colonial charity model, my effort is to bring about transformation in mind sets by enabling the affected households to discard the usual post disaster cycle of dependency and adopt a culture of self reliance and self sufficiency within a few short months. I have shown that by placing faith in people’s own capacities, and utilizing principles of Barefoot Resource Economy that would ensure the use of untapped human, natural, community and waste resources, low cost, affordable and sustainable are possible in order to reach out to millions of the target group. These are people who belong to the most marginalized sections, living at the bottom of the pyramid (BOP).

As Architect of the Poorest of the Poor, my work is focused on displaced populations, suffering from extreme poverty and are mostly homeless. Accordingly, I have been engaged in working on climate resilient structures using design alternatives to enable the destitute to rise above adversity. My motto being Zero Carbon, Zero Cost and also Zero Donor, in order that we could attain Zero Poverty. I need to ensure that all methodologies I design are in pursuant to a holistic model, which would assure life safety, make them food secure and enable them to carry out disaster preparedness. Instead of handouts, my Barefoot Social Architecture or BASA provides principles to foster self reliance through knowledge sharing and capacity building in low tech low impact strategies using local sustainable materials and designs that draw upon tradition and age old wisdom.

Working to rehabilitate tens of thousands after devastating disasters, I have demonstrated on a large scale how through their own effort and utilizing their meagre and untapped resources, the displaced and the destitute could become self reliant and attain a better quality of life through their own effort.

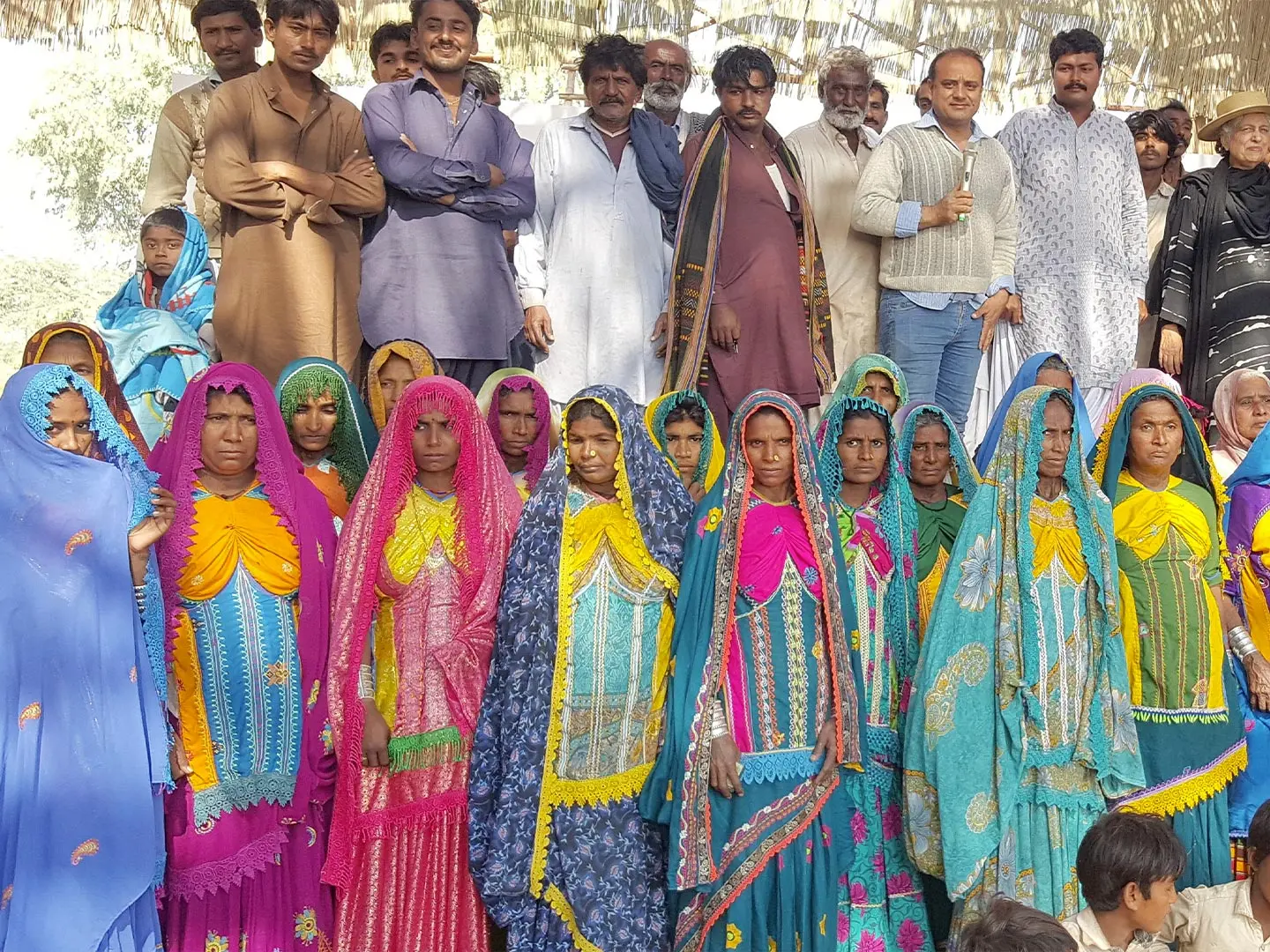

Since my work is largely with climate migrants or displaced communities as a result of a natural disaster, it is women and children who suffer the most due to these calamities. From very early in my practice, beginning with the social housing in early 1970s, that I designed for vulnerable communities living in a storm drain, I had learnt to interact with women, I felt that since it is women and children who spend most of the time in their homes, the involvement of mothers and their point of view was important to design habitats that would be meaningful for them.

In a large public assembly where the community was invited for my presentation. The first question the women in the assembly asked was “If you move us to three storey walkups, where would our chickens go? I told them, here are the open spaces at all levels, where your chickens will roam, and your children would play. Since I had designed my housing by drawing inspiration from Pakistan’s historic towns, I had incorporated open to sky terraces or courtyards with every housing unit. Although the family size is large, however, the built area for poor families is always limited. I had provided the terraces to provide extra living space but also where they could grow vegetable and rear chickens for extra food for their families.

Zero Carbon Cultural Centre, Makli, Pakistan

It was really when I began to work in the humanitarian field that I understood the important role women could play. If it was the special earthen stove, it is the rural housewife that spearheaded it – self building a couple of hundred thousand stoves because it provided them with respect and dignity. If it is climate resilient one room houses or eco toilets, it is women who continue to building them, because it is they who feel the need, as this accommodation would provide them with security and privacy. Because of my use of zero carbon local materials, women feel particularly comfortable in undertaking building construction as they can use their own skills and creativity to beautify and personalize each structure. For me each one of such items is a co creation in a process of co-building, which has given agency to those who never possessed a voice.

Women community, Pakistan

I believe today the key to sustainability is Decarbonize, Decarbonize, Decarbonize. Unless we begin to lower the carbon footprint in all we do, we will continue to deplete the planet’s resources. Once we begin to use natural locally available resources it becomes clear that adopting alternative lifestyles, can free one from many pressures and stresses. If, as consumers, we demand products that will help us to lower the carbon footprint in our lives, suddenly we are cutting costs for ourselves, using materials and techniques that would sequester carbon rather than emit carbon, we are likely to end up with a feel-good lifestyle, because we know we are protecting our next generations.

Rifugio di emergenza

In order to remain relevant to society, the profession of architecture needs to branch out in divergent directions. The earlier ways of delivering to clients who would commission and dictate the outcome largely for their own benefit, are likely to gradually dwindle as the disparities and difficulties for common people keep rising. There is a welcome understanding, particularly among young professionals that the world today has changed - issues of climate change disasters, climate and conflict driven migrants, global warming and rising sea levels are threatening our very survival. Architects have to be ingenious and innovative to deal with such issues that earlier generation could have only imagined. Sustainability and lowering the carbon footprint, along with mass scale affordable housing and the importance of carbon neutral techniques will become paramount in the vary ways we design. Architects, with their training in creative design, must remain in the forefront to devise sustainable ways that would maximize the potential of the people and the context.

Work in progress

Stories

Stories