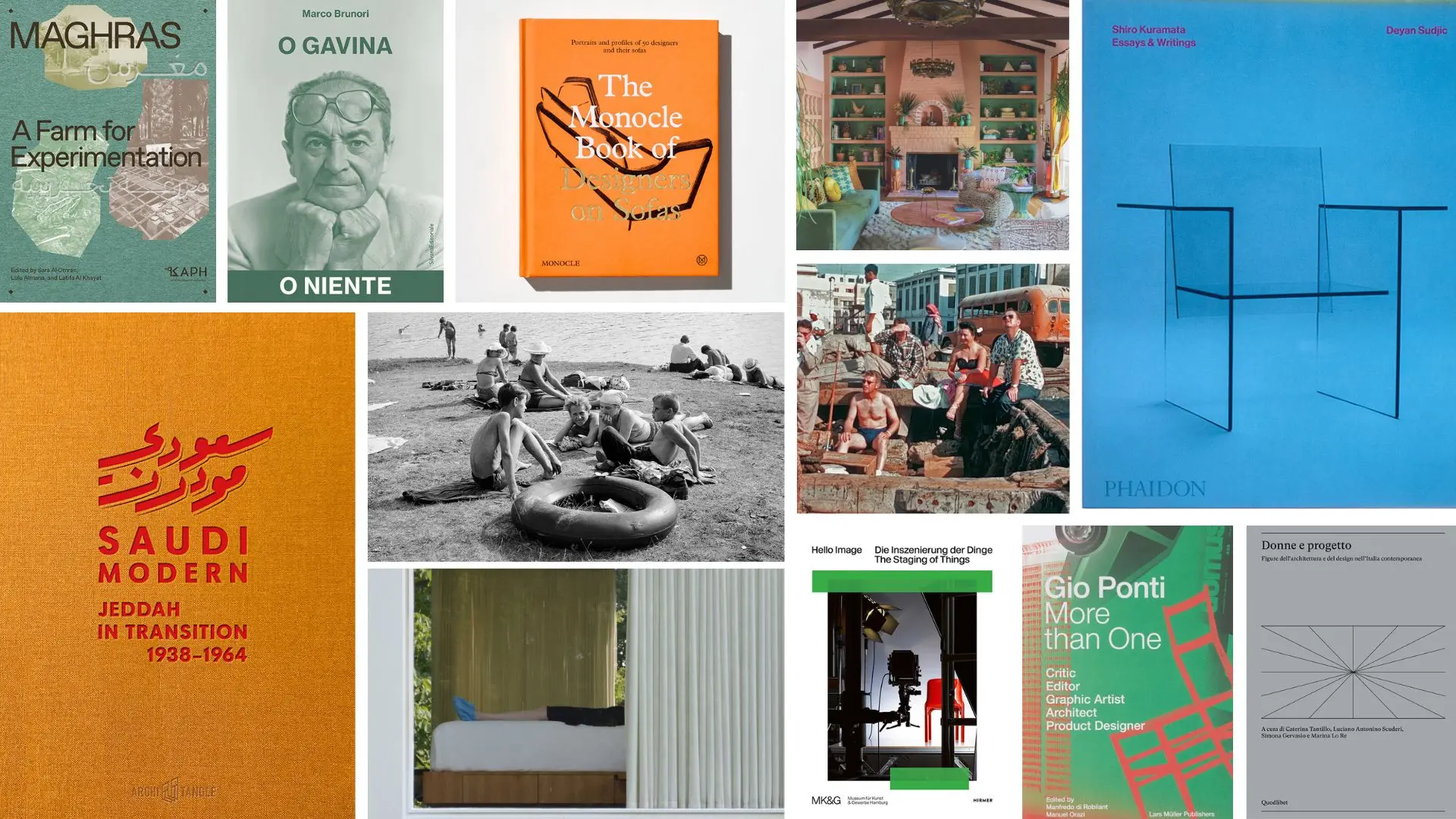

A journey through women’s interior design, three iconic monographs and the links between design, photography and marketing, up to the transformation of Jeddah, social innovation and a reportage by Branzi and... 50 designers on the sofa

Jane Withers. Ph. Credits Paola Pieroni

Acclaimed curator with a clear agenda, Jane Withers answered to our questions on some of her most recent projects and the sort of conversations they sparked around design’s role to inspire climate action

Jane Withers wants to open discussions on how things could be done differently. Her work, which spans design consultancy, concept development, curation, creative direction and writing, has a clear agenda: raising awareness on environmental issues and inspiring change through design.

Taking inspiration from ancient times, indigenous cultures and social activism, her London studio has created critically acclaimed exhibitions, installations and events in collaboration with Victoria and Albert Museum, Royal Academy of Arts, and the British Council among many others. Following an intense and productive year, we sat down with Withers to talk about the impact of some of her most recent projects.

Water Tasting using Moringa seeds for purification by Arabeschi di Latte. Commissioned by Jane Withers Studio for Water Futures research programme curated for A/D/O New York. Ph. Credits by Metz + Racine

Design can be a powerful persuader. A valuable role for design research is to present alternative visions of the future and show that change is possible. But the challenge in the context of the climate emergency is taking these outlier ideas and developing them into solutions that can have real impact.

This needs a transdisciplinary approach, and making these connections and bringing together different areas of expertise is essential. And I think we’ve had a period where a lot of concepts and ideas around countering the environmental challenge have been thrown up, but now it’s about getting them into reality and convincing people to adopt them.

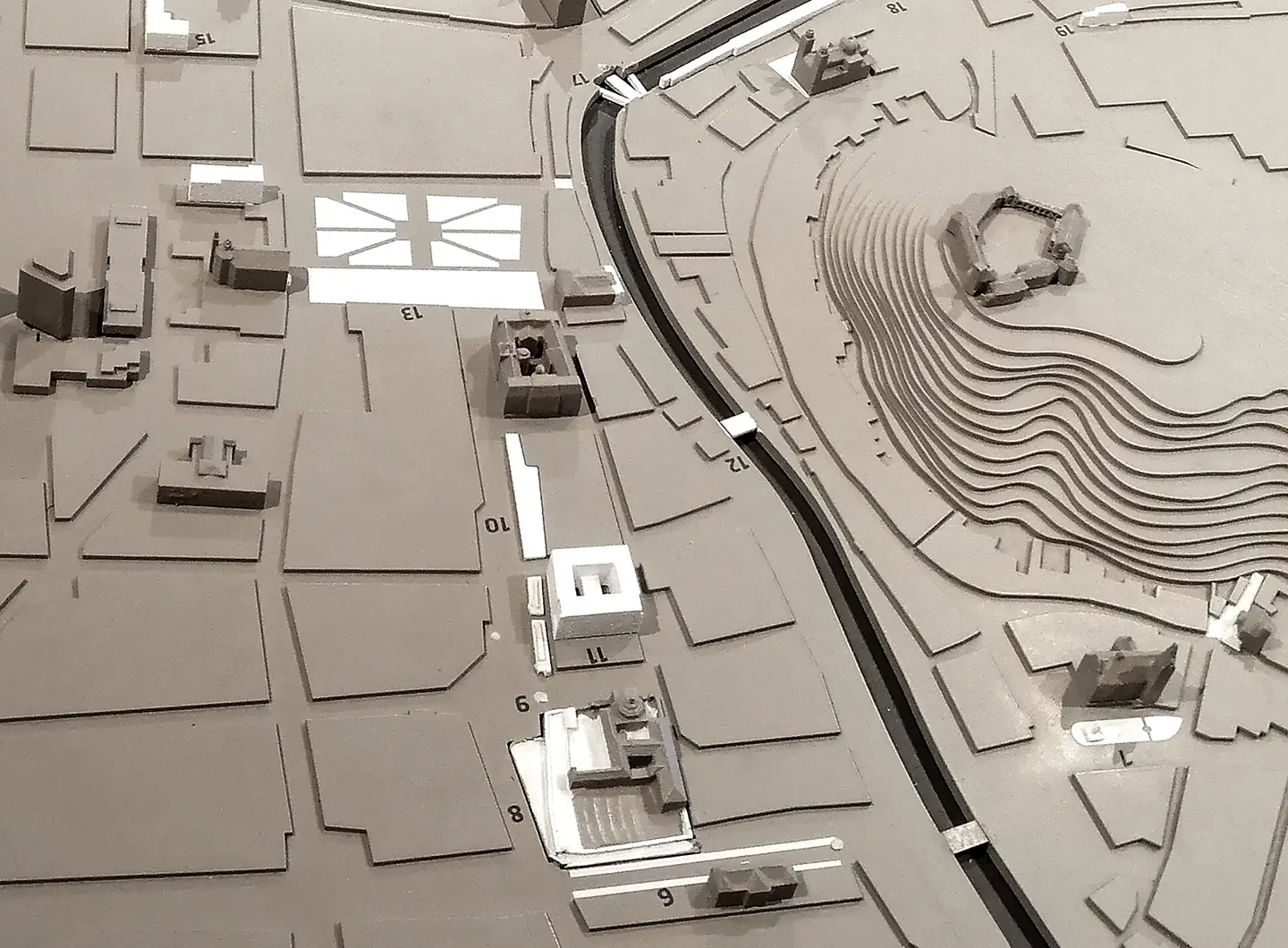

Model of Plečnik’s Ljubljana. Ph. Credits documentation MGML

It goes back a long way; I guess it sort of galvanised through a personal interest in, or even obsession with, water. I’d always been interested in global bathing cultures but when I was teaching at the Design Academy, I began looking into different water cultures in more depth - Ancient Greece and Rome, the Namibians, Indonesian temple culture, Indian step-wells - dipping into different periods and cultures... So many of the ways we treat water today no longer make sense in the context of the water crisis. It’s madness that we flush drinking water down the loo or let rain run away.

So, what could the alternatives be? I wanted to create a more expansive, open-minded approach and set of references for designers to explore. I quickly realised that part of the problem is that we no longer value water, with industrialisation we have made collection systems invisible and we don’t have an emotional connection to it anymore. I realised that it is as much a cultural as a technological problem, and this is an approach I take to many of our projects.

The title Super Vernaculars is deliberately almost a contradiction in terms, there’s strangeness in there that I hope makes it provocative and memorable at the same time. All cultures have a store of vernacular intelligence, but in the West, we’ve largely lost that understanding.

Yet, I have been observing a lot of designers and architects drawing on vernacular ideas again, not looking backwards, but using vernacular practices and wisdom as a source of inspiration, a playbook of ideas for the future. The idea is to use Super Vernaculars as a platform to create awareness of this movement and to interrogate this strand of regenerative design.

Adam Štěch, Objects of refinement. Ph. Credits OKOLO

I do think there is increasing engagement with these themes, but there’s still a long way to go to put them into action. The debate has changed considerably in the past two or three years, but it still needs systemic change to put it into action at scale. Our work is often about giving oxygen to alternative ideas.

Certainly there’s room for design as activism, we need design that can inspire and incite change. But at the beginning, there should be an understanding of circularity and regeneration.

Sečovlje salt panes. Ph. Credits M. Granda, Outsider magazine

Bio has had an interesting track record for the last decade, it’s focused on topical issues and developed a sustainable agenda. We aim to continue this and also open up research into new areas.

The Super Vernaculars theme is really timely and so I want to use the biennale as a platform to illuminate alternative approaches to some of the big problems we face like water and waste, construction and agriculture and show that there are other possibilities. I’m interested in legacy and how we can use Bio to seed long term change. Part of the biennale is an exhibition exploring the Super Vernaculars theme and part is a production platform bringing together international mentors with local design teams to collaborate on commissions that address regional challenges like water and food waste. Some really interesting teams have emerged bringing together experts from science, design and the humanities and I’m excited to see the fruits of this and the influence it can have both locally and more widely.

We are also working on an environmental audit of the biennale and looking at how we can improve our practice and create a set of guidelines for future bios and hope this will help achieve long term impact.

Bio 27, Slovenia’s 27th Biennale of Design

Formafantasma on Salone Raritas

After the “Drafting Futures” Arena conference space, the Salone Library, and the Corraini Bookshop, the Formafantasma creative duo – Andrea Trimarchi and Simone Farresin – has also designed the new “fair within a fair” setup dedicated to rare objects. Here’s their preview

Stories

Stories