From the Waldorf Astoria New York to the Hotel Danieli in Venice and the Aman Rosa Alpina: the reopenings that redefine luxury and contemporary hospitality.

Organic Architecture: from Wright’s six points to its 1000 interpretations

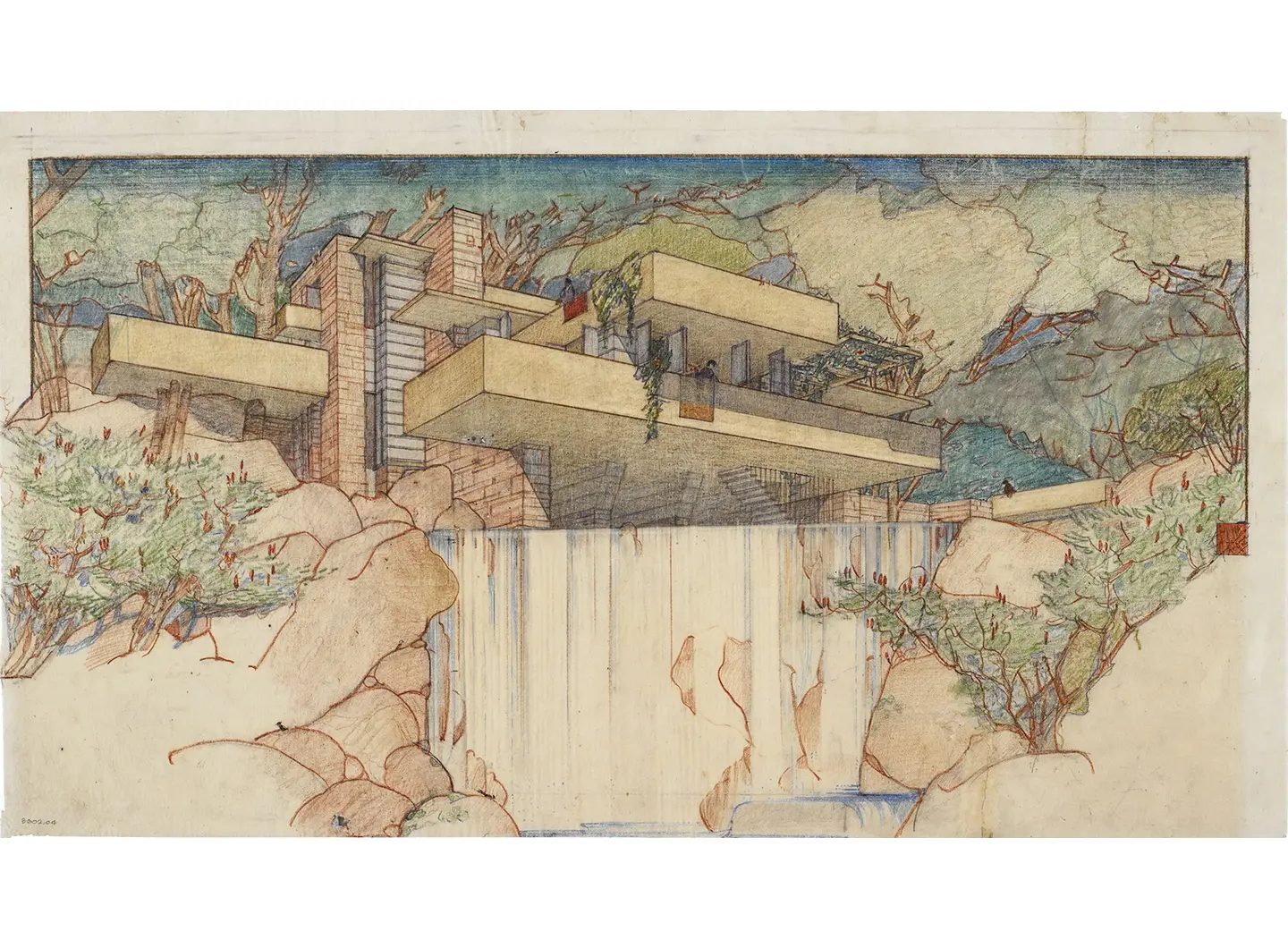

Frank Lloyd Wright, Fallingwater, Mill Run, Pennsylvania, United States, 1936-39, Ph. lachrimae72 – via Wikimedia Commons

During the twentieth century, organicism in organic architecture stood as an alternative to modern functionalism, with projects conceived in dialogue with the natural environment

There are a great many interpretations of the nature, characteristics and qualities of Organic Architecture these days. But any discussion about this architectural movement cannot but start by mentioning the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, who dedicated his career to defining and redefining the concept of organicism in architecture. This was the approach that made his output unique, capable of responding to the new challenges of modernity, technological progress and social change, and maintaining a consistent dialogue with nature.

As well as his practical architectural oeuvre, Wright set down his concept of Organic Architecture in writing. His two essays published in 1908 and 1914 in the journal Architectural Record are well known: “A sense of the organic is indispensable to an architect […] A knowledge of the relations of form and function lies at the root of his practice; where else can he find the pertinent object lessons Nature so readily furnishes?” he wrote in his first essay, going on to say in the second part of his argumentative text: “By organic architecture I mean an architecture that develops from within outward in harmony with the conditions of its being as distinguished from one that is applied from without.”

Frank Lloyd Wright, Fallingwater, South elevation. Pencil and colored pencil on paper, Ph. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art/Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

Organic Architecture: the six propositions illustrated by Frank Lloyd Wright

1) Simplicity and repose are qualities that measure the true value of any work. Wright saw the need to simplify the design of structures, reducing the number of distinct rooms and rethinking them as open spaces, including those to be contained in a single room. Windows and doors become part of the ornamentation of a structure, and furnishings are also part of the structural whole;

2) The unique style of a building should respond to the unique personality of the person for whom it is designed;

3) A building should look as if it were growing spontaneously in its context, and be modelled as if it had been created by nature and landscape;

4) Colours call for the same degree of coexistence with natural forms, so tap into woods and fields for colour schemes;

5) Allow the nature of the materials to shine through, allow their nature to become an intimate part of your scheme;

6) Buildings must be sincere, true, gracious, lovable and full of integrity:

Frank Lloyd Wright, Fallingwater, structure detail, Ph. Daderot – via Wikimedia Commons

Examples of Organic Architecture

His vision took shape through a few iconic projects, including the Johnson Wax Administration Building and the Kaufmann House, also known as Fallingwater, a building above a small waterfall formed by the Bear Run River. Here the dialogue with nature has no parallel in 20th century architecture – this building is undoubtedly the most virtuous (and perhaps the most extreme) example of organic architecture there is.

Wright’s thinking and his work transcend a narrow concept of modernist, radically functionalist thought. The house is not a machine to be inhabited, but an organism that dialogues with the life of human and non-human beings, with those who live in it and with the natural context.

His precepts were subsequently adopted, reinterpreted and updated by a large number of designers, throughout the twentieth century and still today. One of the architects subscribing to this particular architectural strand was Bruce Goff, a direct follower of Wright. Among his best-known works is the Bavinger House, a building with eccentric shapes and characterised by great skill in the unusual use of materials: the house was built using a walnut tree struck by lightning and found on the spot, a truck, pieces of naval and aeronautical production, fragments of rock ...

Bruce Goff, Bavinger House, Norman, Oklahoma, United States, 1950-55, Ph. Jones2jy – via Wikimedia Commons

Organic Architecture in Italy

In Italy, the notion of Organic Architecture was diffused mainly by the historian and critic Bruno Zevi who, after several years living in the United States, returned to Italy in 1944, bringing with him a new vision of architecture. The following year he founded the A.P.A.O. Association for Organic Architecture together with various prominent figures, including Mario Ridolfi and Pier Luigi Nervi. Zevi is also the author of the seminal book Towards an Organic Architecture.

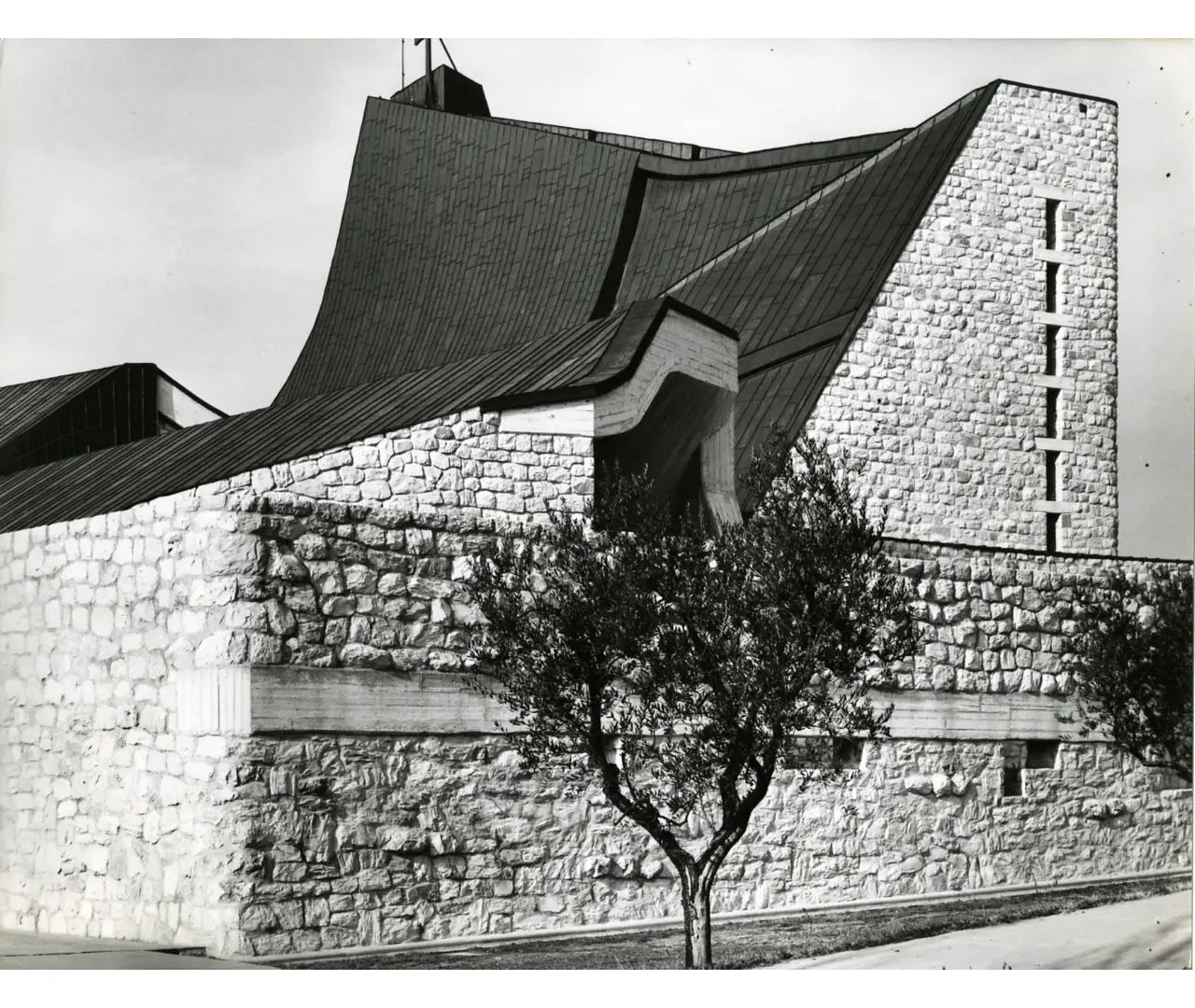

The list of interpreters of organicism in architecture is long and not necessarily exhaustive. They include Alvar Aalto, who interpreted a specifically Finnish tradition to design buildings that were always in dialogue with the surrounding environment; Jørn Utzon, the Danish architect and author of the famous Sydney Opera House; Paolo Soleri, who theorised Arcology (a mixture of “architecture” and “ecology”) in the Sixties; Hans Scharoun, the architect of the Berliner Philharmonie, and Giovanni Michelucci, (also) famous for the Church of San Giovanni Battista in Campi Bisenzio …

Giovanni Michelucci, church of Saint John the Baptist, Campi Bisanzio, Florence, 1960-64, Ph. Paolo Monti - Available in the BEIC digital library and uploaded in collaboration with Fondazione BEIC. The image belongs to Fondo Paolo Monti, owned by BEIC and located at Civico Archivio Fotografico in Milan

The variety of approaches, projects and paths shows that Organic Architecture has never been a defined style or a closed group of designers. Wright's Propositions were not Le Corbusier's Five Points of Architecture, that is, instructions to be followed dogmatically. Rather, organic architecture is a broad design horizon, an attitude to be adapted to the places, culture and sensitivity of the designers.