Pure volumes, minimal or non-existent decoration, primacy of functionality, harnessing new materials: from the Casa del Fascio in Como to the railway station in Florence, the story of an experimental period that, after almost a century and several attempts at damnatio memoriae, remains a tangible presence in Italy.

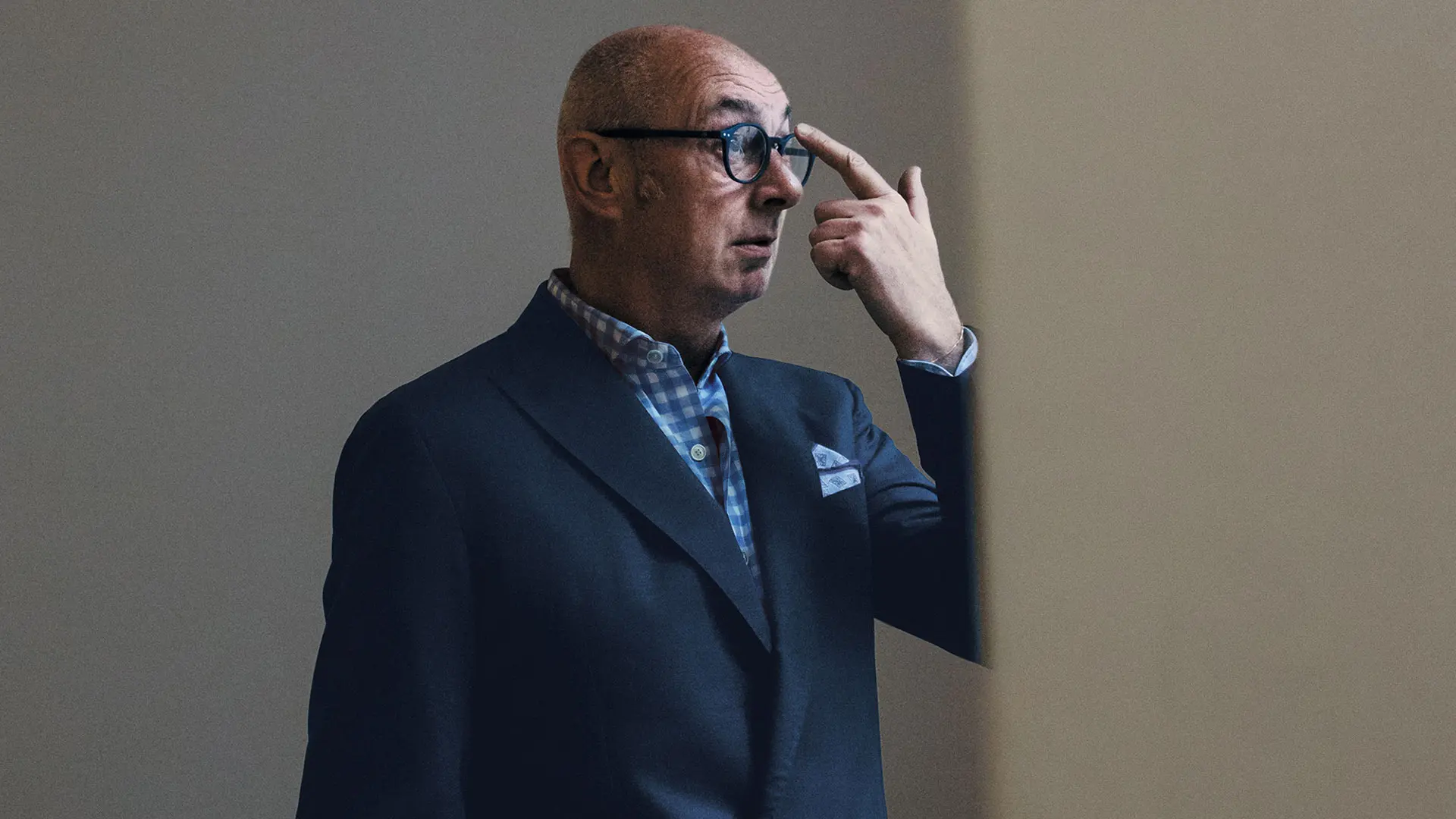

Piero Lissoni

© Matthias Ziegler

His mantras include working with clients who produce and think Italian-style. Famous for his error philosophy, which derives from liberating oneself from the obligatory relationship between form and function (so insufferably German).

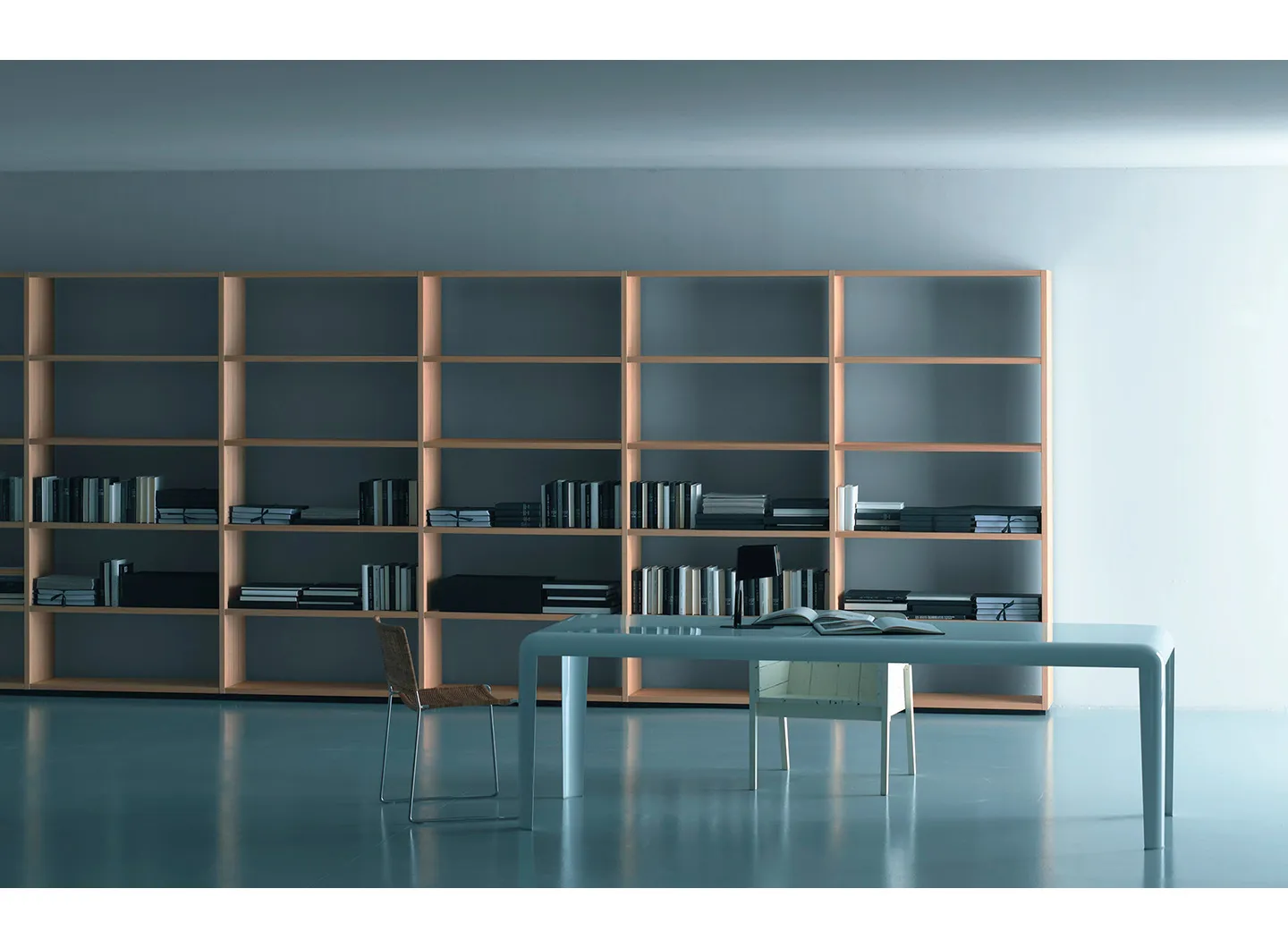

Architect, designer and graphic artist Piero Lissoni is one of Italy’s most renowned creatives on the world stage. What strikes you at first sight is his somewhat dandified and somewhat intellectual appearance, his freedom of thought and his sparkling, occasionally sharp conversation. His work is appealing because of its lightness, its rigorous style and that hint of imperfection that derives from his shrugging off the obligatory relationship between form and function that he describes as so unbearably German. A de facto aesthete, he does not, however, disavow errors, which he regards as a fundamental reflection of our ability to learn and improve. “The key to design rests in flushing out the error and turning into a strong point. If you don’t raise the bar and never exceed the limit, we can never move forward,” he comments in an interview. His order book is crammed with all the top names in Made in Italy – Alessi, Boffi, Cappellini, Cassina, Fantini, Flos, Glas Italia, Kartell, Lema, Living Divani, Poltrona Frau, Porro, Tecno and a great many others – testament to one of his mantras: he will only work with clients who produce, build and think Italian. He designs contemporary and minimalist projects, pure volumes and restrained shapes, which mask a technological complexity that stems from meticulous research into materials and production techniques. They are always born of a close, intense daily dialogue with his interlocutors.

Design is an intellectual practice, a discipline, a process – you study, you try, you change, and you study more, you try, you change and the project gets under way. Every design stems from a dialogue and a daily debate, from working extremely closely with the client. I can say that an evolution took place over the years, I became a bit more sure of myself and I started to see a sort of continuity in the things I designed. But, if I have to be truly honest, of all the things I’ve designed there isn’t one I like.

The great thing about mistakes is that you have no control over them, otherwise they wouldn’t be mistakes. Every project has this marvellous ability to build, generate and produce mistakes, sometimes entirely unwittingly, easily made because some things are undervalued or taken into consideration too late: a proportion, a depth, a height, there are so many factors … Sometimes the material behaves differently, though, mysteriously, precisely because the mistake can’t be controlled, otherwise it wouldn’t be a mistake, this ingredient becomes mixed into the alchemic formula – because it is not as precise as chemistry – and suddenly whatever seemed at first sight to be a mistake turns out to be the strength of the project.

I don’t think you can distinguish between these things. Culturally speaking, it’s part of a humanistic approach, gained from the Milan Polytechnic, an approach that teaches you to be versatile and all those things together. You design a building, then you design the spaces inside the building and lastly you design something to insert into the spaces inside the building. Everything is connected.

Every company obviously has its own story to tell. As I said, every project stems from an everyday dialogue, it’s teamwork, but all companies operate in different ways and every company teaches you new things. Being an art director is always part of that humanistic approach, which enables different aspects to be put together: you design objects, you design displays, you design graphics, you design communication. But always with the fear of going wrong on one hand, and on the other a strong sense of responsibility, because as art director you are accountable for the work of many different people.

For me working around the world still means always being myself. The difference is that each time I have to adapt … in reality it’s a bit as if I’m hunting for gold, I dig or sieve and sometimes I come up with things and sometimes I don’t. But the interesting thing is that wherever in the world I am, whether it’s Italy, China or the United States, I adapt to my surroundings. So I try to find a way of preserving the local spirit, what was once known as the genius loci, but on an intellectual and cultural level. If I’m in China, I don’t pretend to be Chinese, but I pick up on various elements and register them, they may be aesthetic or productive, industrial or material-related. The same goes for when I’m in Italy, Paris or New York.

I think it’s absolutely vital that young people take on board the fact that making design is a job, a profession, work that calls for a great deal of discipline and a great deal of curiosity. Not to mention a great deal of responsibility. I also think it’s important to have respect for and an awareness of one’s own tradition; otherwise you have no key to the future. Without a refined and in-depth knowledge of your own history and culture, it’s impossible to grasp what the future might be. At that point you will be able to access new technologies, new materials … but they won’t work without culture and ideas behind them.

A play space is a serious matter

Not just fun places, but true places of social focus, where individuals gather, create bonds and build trust

The second edition of the Roundtables on Milan Design (Eco) System

Discussions ranged from the role of cultural policies and training, the appearance of new publics and emerging practices, all the way to innovative networks between territories and design. This is an account of the day’s work on Thursday 25 September, as part of the research project promoted by the Salone del Mobile and the Politecnico di Milano