Smart and sustainable purchases: how to make the most of the appliance bonus and how to apply. Requirements, amounts and limits to be aware of

Treasure Garden in Taichung, Taiwan, 2018. Photo Sam Siew Shien

“I see the work of an architect as that of a craftsman, used to moving between benches to carry out the business of exchange and comparison that projects demand”. In conversation with Antonio Citterio

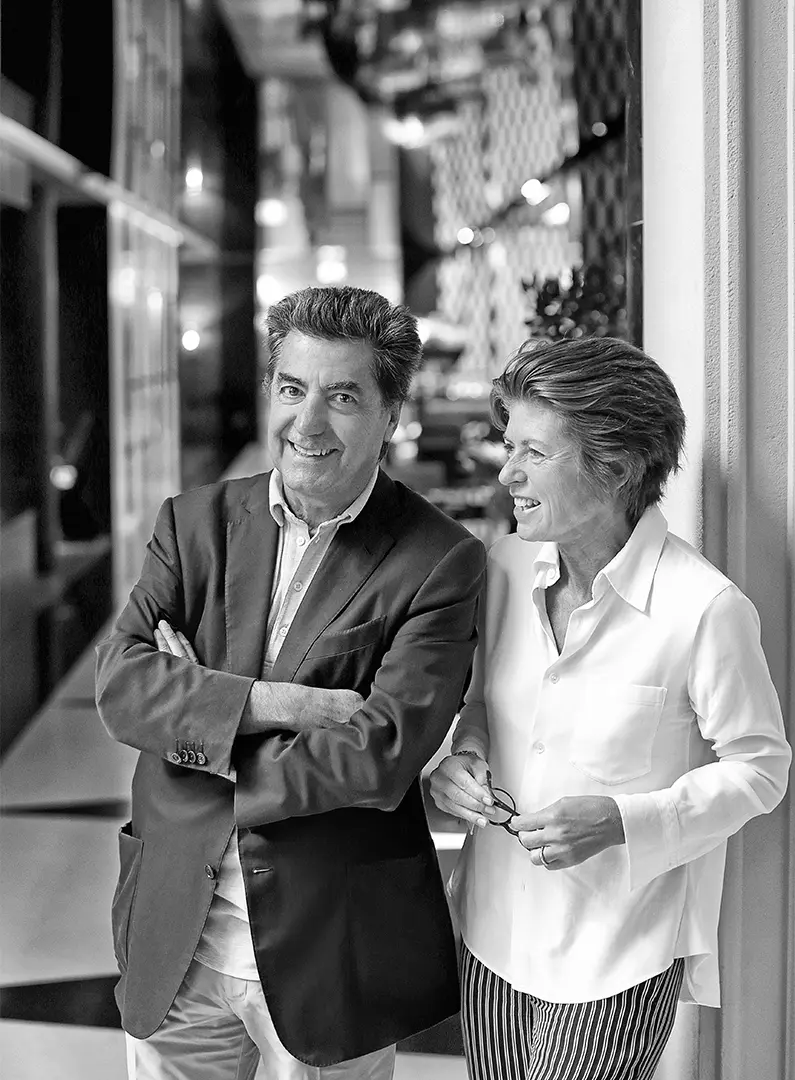

Sobriety, innovation, consistency, relationships: Antonio Citterio, a true long-seller, in a nutshell. The architect saw three anniversaries collide in 2020: his 70th birthday, the 50th year of his career and the 20th anniversary of his Milan-based studio, which takes on large-scale projects. In the meantime, his office has become ACPV Architects, the second part of the acronym referring to the architect Patricia Viel, CEO of the group, with eight partners, a staff of 170 people and a series of accomplishments at global level.

Winner of the Compasso d’Oro-ADI in 1987, in 1994 and a Lifetime Award last year, Citterio affirmed The Importance of Being an Architect in a 2021 documentary film. The book “in which I try to explain my thoughts through design from 1970 to today” - that intellectual agility that allows him to work out a design for a sofa or for a skyscraper with equal clarity - is due to be published in a few months’ time.

Antonio Citterio and Patricia Viel, photo Settimio Benedusi

There’s certainly more of an appetite for travel, more people around and the approach to work has changed, who knows whether that’s a long-lasting trend. Many people choose to work from home, it remains to be seen if there’s a positive effect on efficiency or if it will create a sort of “happy downgrowth.” There are cases in which this isn’t even a possibility – for those working in health or in factories, for example – which could lead to discrimination.

I really miss the people who aren’t in the studio. I see the work of an architect as that of a craftsman, used to moving between benches to carry out the business of exchange and comparison that projects demand. Basically, I don’t think it’s right, perhaps because I belong to a different generation. I actually find Zoom meetings really hard going, on the other hand, they’ve cut down on travel a lot: when my children were little, they thought I had another family because I was always going to Basel, to see Vitra.

There’s been a sort of explosion, as if people realised they were living in not entirely suitable places. Things are still a bit confused, but our homes do need to change. There’s undoubtedly high demand for good quality living spaces. We are currently working on no less than five skyscrapers in the Far East. Equally, general sensitivity towards sustainably has suddenly improved, not least as a consequence of the recent wars.

Sukhumvit THIRTY-EIGHT, Bangkok, Thailand, 2022. Photo Wison Tungthunya

Even 25 years ago, at Vitra, we had started wondering about the end life of products, it seemed like science fiction then. In the upholstereds sector, for example, one of the great problems is the use of polyurethane, which can’t be recycled due to its composition. This led to the conception of products such as the Esosoft sofa for Cassina, the ID Cloud chair for Vitra and even the Klismos range for Knoll.

If it’s from a luxury market bracket, then it does. What we should be doing is asking ourselves whether it still makes sense to produce a sofa and then send it to America by boat. What will happen is that optimisation will become more logical and production localised, which will slash transport costs, like in the fashion world.

Again, comparing it with fashion, I wear clothes that cost very little, then I mix them with more sophisticated pieces. It’s always the economy that drives the trend and mid-market products are undeniably disappearing, which will trigger a crisis.

I’ve never thought of design as an expression, instead I focus on the synthesis of the product. I actually introduced the sofa with a chaise element in 1986 (Sity for B&B Italia, which netted a Compasso d'Oro, ed.), which is quite common these days, but I invented it! My typological experiments – with kitchens, bathrooms and wardrobes – represent huge changes inside the domestic environment.

Knoll, Klismos, design Antonio Citterio, 2022. Photo Federico Cedrone, courtesy Knoll

That’s an interesting observation and, without wishing to cause ructions, it should be said that for many years designers weren’t well regarded in the architectural world. In actual fact, history was written by the greats who were active in both fields, such as Gio Ponti, Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

Indeed, we had Luigi Caccia Dominioni, Vico Magistretti and Gio Ponti: being self-sufficient is part of our tradition. What I mean is that furnishing and interior design were once an integral part of architecture. The schism happened during the Eighties, fuelled by the Anglo-Saxon world, there were no schools devoted exclusively to design. The concepts of creativity and innovation tie in much more easily with design, whilst architecture involves problem-solving.

I honestly don’t know. This living like bees or ants is so far removed from my vision of architecture and of the city. You just need to go and see what’s been done in Italy, on a small scale, with projects such as Le Vele in Naples and the Nuovo Corviale in Rome: unsuccessful experiments that are almost laughable.

I set up my studio when I was just 20. I was lucky enough to get to know Piero Ambrogio Busnelli of B&B Italia, Doug Tompkins of Esprit and Rolf Fehlbaum of Vitra: three seminal meetings with far-sighted creators of the first products to map out a direction. I remember Esprit, the Amsterdam headquarters (1987), which also impacted my private life: I got to know a young American architect who later became my wife, Terry Dwan.

Esprit headquarters, Milano, 1987. Photo Gabriele Basilico

He was actually the person who flagged me up for the Milan project. My job is linked to the dialogue and the give and take of acquaintances that make life go round; the same goes for products – there are some magic moments, made up of personal relationships and companies. Then other dynamics come in, commercial demands that have to factor in competition, innovation, which isn’t the case when you’re building. Other factors come into play in architecture, but first and foremost it has to become a place.

Not everyone carries it off, often the result is just a great architectural statement. I recently visited the Coal Drop Yards area behind Kings Cross station in London and found it interesting, with a positive feel that I don’t find in America, for example. I loved New York, my two children live there, but right now I no longer find it stimulating from a creative point of view. We’re not trying to be innovative at all costs, I’m not interested in leaving my own mark on a building.

It’s a question of approach. For instance, Zaha Hadid and I were friends despite being culturally different. I remember her project for a house in Russia (Capital Hill Residence for Vladislav Doronin, ed.), when I was called into to do the interiors. I was cagey, I answered that I would have to talk to her before I could accept. Zaha intimated: “absolutely not, don’t even try!” She was insufferable and likeable at the same time, with an extremely powerful expressive character – everything had to be run by her. Creating a museum like MAXXI with slanting walls frankly makes no sense.

Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe – I’ve always looked up to them; Louis Kahn, who in some ways is the most similar to what I’ve done. I observe everyone, famous or not, and I always make an effort to understand.

Saudi Arabia, a land of new balances

Saudi Arabia is the largest FF&E (Furniture, Fixture and Equipment) market in the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region. In 2024, it reached a value of $7.2 billion, fueled by economic diversification, rapid population expansion and reforms of the Saudi Vision 2030 strategic program.

Introducing “Salone Raritas”: the new Salone del Mobile.Milano exhibition space dedicated to limited edition design and high-end creative manufacturing

Salone Raritas will make its debut at the 64th edition of the trade fair. Curated icons, unique objects, and outsider pieces: the first direct interface between the world of special edition design, antiques and high-end craftsmanship and the professional design market professional design market (architects, interior designers, contractors, developers, dealers, etc). Leading galleries and an international audience will come together on a platform driven by a strong curatorial vision, designed to foster long-term relationships and generate business opportunities.

Stories

Stories