Created in collaboration with the Salone del Mobile.Milano, the building features a linear and discreet design, designed to blend into the surrounding environment at high altitude in a deep connection with nature

Modernism: the architectural style that represents the American dream

Charles and Ray Eames, Eames House – Case Study House #8, Los Angeles, 1949 - Ph. Gunnar Klack - Own work Wikimedia Commons

In the twenty years following World War II, in the United States and particularly California, an architectural movement developed that renewed the dictates of Central European Modernism: Californian Modernism.

Can a painting become the manifesto of an architectural style? This is what happened with David Hockney’s celebrated painting A Bigger Splash. It is an extremely effective depiction of the features, climate and mood of Californian Modernism, an architectural movement that developed in the twenty years after World War II in the United States, especially in the Golden State. In his book The Good Life, the Spanish architect Iñaki Ábalos writes: “When David Hockney painted A Bigger Splash in 1967, he probably never imagined that his work would be interpreted as a veritable architectural manifesto. Yet it soon happened, since already in 1973 it appeared on the cover of Los Angeles. The Architecture of Four Ecologies, perhaps Reyner Banham’s finest and best-known book. That painting epitomized a way of understanding architecture, the city and their relationship with nature that would become part of the memory of the twentieth century.”

The painting depicts a sunny swimming pool in Los Angeles. Unusually for Hockney’s works from this period, there is no human figure in the scene, only the splash that suggests someone has just plunged into the water. Behind the pool is a pink modernist building, whose large windows reflect the silhouette of the neighboring buildings. Hockney’s painting represents a way of understanding life and the home remote from the values of Central European rationalism. As Abalos writes; “The house, let’s say it right away, has nothing to do with the positivist house, despite the fact that 20th-century historians have often associated it with the dictates of the ‘International Style’, the self-styled Modernist Movement that Europe exported to America.”

David Hockney, A bigger splash, acrylic painting on canvas, 1967 - Ph. David Hockney, courtesy Tate

Modernist architecture: characteristics

Modernism gives a unique interpretation to the modern canons of architecture, adapting styles and approaches to California’s weather, materials, and lifestyles. The architectural movement takes two key principles of modern architecture to extremes: the connection between domestic and open spaces, and formal simplicity. Each house is adapted to the landscape that surrounds it, creating a symbiotic relationship that makes them inseparable. Each is then the reflection of the personality and lifestyle of its inhabitants.

So, regardless of Hockney’s painting, what are the most representative buildings of Californian Modernism? A notable instance is the series of Case Study Houses, a residential program promoted by John Entenza, editor of the Los Angeles magazine “Arts & Architecture”, between 1945 and 1966. This is not only the most important architectural experiment on the theme of the single-family residence, but also a very important experiment in architecture photographed for the purposes of advertising. The 36 projects built were documented by the same photographer, Julius Shulman, reinforcing the unified narrative of the operation.

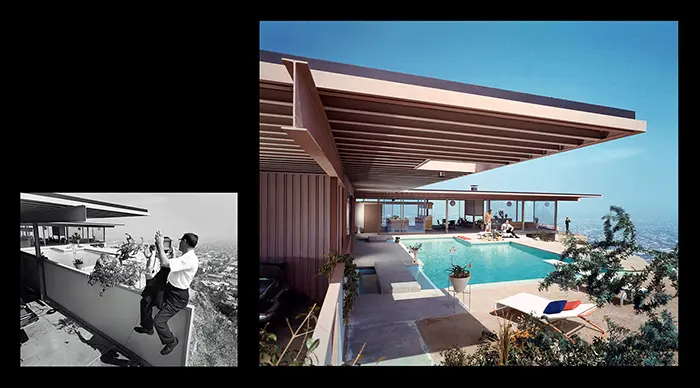

Julius Shulman photographs the Case Study House #22, 1960

Modernism: examples of buildings

The magazine Domus has published a survey of the principal houses built by the program. “The first experiments — soon rising to the status of icons of what is known as Californian Modernism — worked on the combination of layout and structural solutions (mostly timber or steel frames). Still partly related to the European design legacy, the buildings at Pacific Palisades stood out in this first group: the Eames House (Case Study House #8, 1945-49), the Entenza House (Case Study House #9, 1949) designed by the Eameses with Saarinen, and the approach to inclusion in the landscape and structuring of domestic space in the house designed by Neutra (Case Study House #20,1948). From 1950 on, the experiments became more definite in typology, with almost all of them featuring steel frames. The most famous projects embodying the archetype of the modernist Californian house appeared. Examples are Koenig’s Stahl House, with its full-height glazed envelope and slim metal structures cantilevered above the city, and Ellwood’s houses, which combined sequences of open and closed parts, transparencies and opacities, constantly enhancing the simplicity and lightness of their volumes and structures together with the linearity of their construction. This was the case of House #17B (1956) and the Fields House (#18, 1958), both in Beverly Hills.”

Pierre Koenig, Bailey House – Case Study House #21, Los Angeles, 1959 - Ph. Ilpo Sojourn, via Wikimedia Commons

The Californian Modernism of Richard Neutra

When it comes to Californian modernism, we inevitably have to reckon with the work of the architect Richard Neutra. A pupil first of Adolf Loos and later Frank Lloyd Wright, Neutra developed the concept of biorealism, whereby the architect has to identify and harmonize different factors: nature, functionality, culture, lifestyles... In 1954 he presented his ideas in a book that is still valid today, although neglected: Survival Through Design. Already in the fifties, Neutra brought together themes concerning the eco-compatibility of buildings with an analysis of the physiological and psychological aspects of dwelling. In this way the designer moved closer to the purpose of a researcher sensitive to the complexity and interaction of the elements that configure and characterize a space to be inhabited, than to the demiurgic role of one of the masters of Rationalism. Nestled in the desert and surrounded by mountains, the Kaufmann Desert House in Palm Springs (1946-47) is considered the highest expression of Neutra’s thought and a symbol of Californian modernism.

In Elle Decor, architect Alessandra Di Palma writes: “In No Country for Old Men, Cormac McCarthy has one of his characters observe: ‘Best way to live in California is to be from somewheres else,’ meaning it is easier for an outsider to grasp the genius loci of a given place. In fact, it was two non-Californians who best made Californian hedonism tangible: the British painter David Hockney and the Austrian architect Richard Neutra.”

Richard J. Neutra, Kaufmann Desert House, Palm Springs, 1947 - Ph. Kansas Sebastian